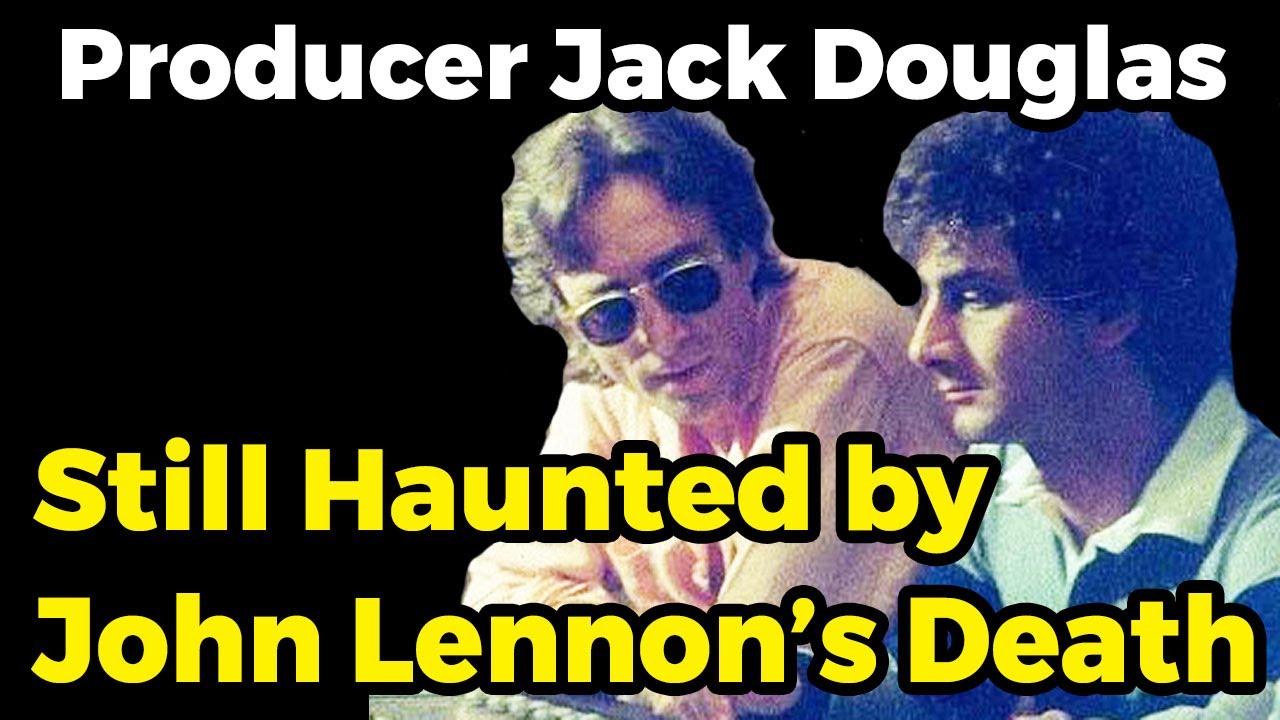

For more than four decades, producer Jack Douglas—one of the most respected architects of rock music—has lived with a private torment so consuming, so bone-deep, that he has never escaped it.

He was there on the last day of John Lennon’s life, inside the studio where Lennon and Yoko Ono were polishing what would become his final recordings.

He heard Lennon laugh.

He heard him dream out loud.

And, in the final moments before the former Beatle walked out the door of the Record Plant in New York City, he heard him say goodbye.

But Jack Douglas did not walk him downstairs.

And he has spent the last 40 years believing that single decision might have changed history.

Douglas, who had already shaped albums for Aerosmith, Cheap Trick, and Patti Smith, always said working with Lennon was different—personal, emotional, familial.

It wasn’t producer-and-artist; it was brother-and-brother.

After a five-year retreat into domestic quiet, Lennon’s creative rebirth through Double Fantasy had electrified the music world.

He was hopeful.

He was energized.

He was back.

On December 8, 1980, he arrived at the Record Plant with Yoko Ono, ready to keep building this new chapter.

The three of them worked on “Walking on Thin Ice,” a track that would later become forever haunted by tragedy.

Spirits were high.

Lennon was playful.

The session went smoothly.

When it ended, Lennon grabbed his coat, called out a cheerful goodbye, and headed for the elevator.

There was no omen.

No sense of danger.

No sign that the world was about to shatter.

But one detail, so ordinary at the time, would become the center of Douglas’s lifelong agony: he did not escort Lennon to the car.

He always walked with him.

Always.

It was a small ritual of friendship and protection.

But that night, Douglas had another session.

A tight schedule.

A professional obligation.

And later that night, Lennon was gunned down outside the Dakota by a deranged fan.

Appearing on The Magnificent Others podcast with Billy Corgan, Douglas finally opened up about the emotional wreckage he carried long after the gunshots faded from the streets of Manhattan.

He describes a grief so sharp, it drove him into isolation.

A guilt so corrosive, it consumed his waking world and invaded his sleep.

“I didn’t want to go outside,” Douglas recalls.

“It was terrible.”

For months—then years—he replayed the night in his mind, searching for a different outcome that never came.

“And I kept thinking,” he confessed, “‘If I was in the car, I would have seen the guy. I would have tackled him. John would be alive.’”

The thought looped endlessly, tormenting him in the quiet hours of the night.

It became an obsession.

A whisper that grew into a roar.

And when the media began pounding on his door—reporters, phone calls, letters demanding testimony, quotes, access to his pain—Douglas shut down completely.

He froze.

The world narrowed to a single room.

His career faded.

His life collapsed.

He spiraled into a destructive cycle of depression and emotional paralysis.

Eventually, he checked himself into rehab—an act of survival he credits with saving his life.

Today, he has been sober for 30 years.

He has rebuilt.

He has healed, in pieces.

But the wound never closed.

Even now, decades later, Lennon follows him—not metaphorically, but literally in dreams.

Douglas says Lennon appears in different places: backstage, at home, in a studio.

The two talk the way they always did.

And Lennon teases him just as he did in life.

“For a bright guy, Jack,” Lennon tells him, “you don’t know anything.”

The comment stings and comforts at the same time.

It is Lennon’s voice, his humor, preserved in a dream-world where he never died at the Dakota, where he walks freely through the creative spaces they once shared.

For Douglas, those dreams are both a haunting and a refuge.

Forty-plus years later, December 8 remains a global wound—one that deepened not only because the world lost a Beatle, but because it lost a voice that had just rediscovered its strength.

Millions remember where they were when the news broke.

TV and radio were interrupted.

Phones rang across households.

People cried in living rooms.

Shock reverberated worldwide.

And Jack Douglas was left with the unbearable knowledge that he had been one of the last people to speak to Lennon when he was alive.

He had heard that final laughter.

He had seen the spark of new possibilities in Lennon’s eyes.

And he had watched him walk out of a studio that had always been a sanctuary—only to step into the night where fate waited in the shadows.

As Douglas tells it, Double Fantasy was not just a comeback album; it was a resurrection.

Lennon had spent years raising his son Sean, baking bread, rediscovering domestic life.

Now he was crafting music again, joyfully, intensely, with the hunger of a man finding his voice for the second time.

Douglas says the energy in the studio was electric—Lennon was relaxed, open, overflowing with ideas.

It is the memory of that optimism—of Lennon not just living but blooming—that makes the tragedy even harder for Douglas to bear.

He often wonders what albums Lennon would have created next.

What tours he might have launched.

What cultural battles he might have fought.

How the world might have been different if one man with a gun had not been waiting under the archway of the Dakota.

Through sobriety, time, and introspection, Douglas has built a fragile peace.

But the fact remains: when he closes his eyes, Lennon is still there.

Talking.

Laughing.

Scolding.

Creating.

Living.

It is a bittersweet comfort—because on some level, Douglas knows that the dream version of Lennon is the only one the world has left.

Today, Douglas speaks about Lennon with equal parts grief and gratitude.

He acknowledges his guilt but also understands, with the clarity that only years can bring, that he could not have controlled the uncontrollable.

He could not have predicted the unthinkable.

He could not have saved a man targeted by obsession.

But the “what if” still lingers.

And perhaps it always will.

As the world reflects on Lennon’s death each year, Jack Douglas continues having quiet conversations with his lost friend—conversations that bridge the living and the dead, the past and the present, trauma and healing.

In those conversations, Lennon remains vibrant, mischievous, brilliant.

In those dreams, the music never stops.

And maybe, in the end, that is where healing truly begins.

News

The Song that Bob Dylan Wrote About Elvis Presley

Bob Dylan and Elvis Presley are two of the most legendary figures in American music history. One is known as…

Raul Malo, Lead Singer of The Mavericks, has died at age 60

The music world is mourning the loss of Raul Malo, the charismatic lead singer of The Mavericks, who passed away…

At 69, Steve Perry Confessed This Was the Song He Couldn’t Finish

Steve Perry’s voice is one of rock’s most iconic and enduring sounds. As the lead singer of Journey, he gave…

Top 6 SHOCKING Things Axl Rose Said About Other Rock Legends!

Axl Rose, the legendary frontman of Guns N’ Roses, is known not only for his iconic voice and music but…

‘You Had ONE Job!’ How Powerman 5000 FUMBLED a Platinum Future

Powerman 5000’s story is one of bold creativity, underground buzz, and a dramatic crossroads that nearly derailed their ascent to…

‘He Knew Last Show Would Kill Him’ Ozzy Osbourne’s Final Moments | Sharon Osbourne Interview

Ozzy Osbourne, the legendary rock icon, cultural pioneer, and beloved family man, gave his final performance knowing it might be…

End of content

No more pages to load