AI analysis has confirmed the Maya Codex of Mexico as the oldest surviving Mayan book, dating to A.D. 1021–1154.

For more than half a century, a mysterious Mayan manuscript lay untouched in museum storage, locked away in darkness, doubt, and controversy.

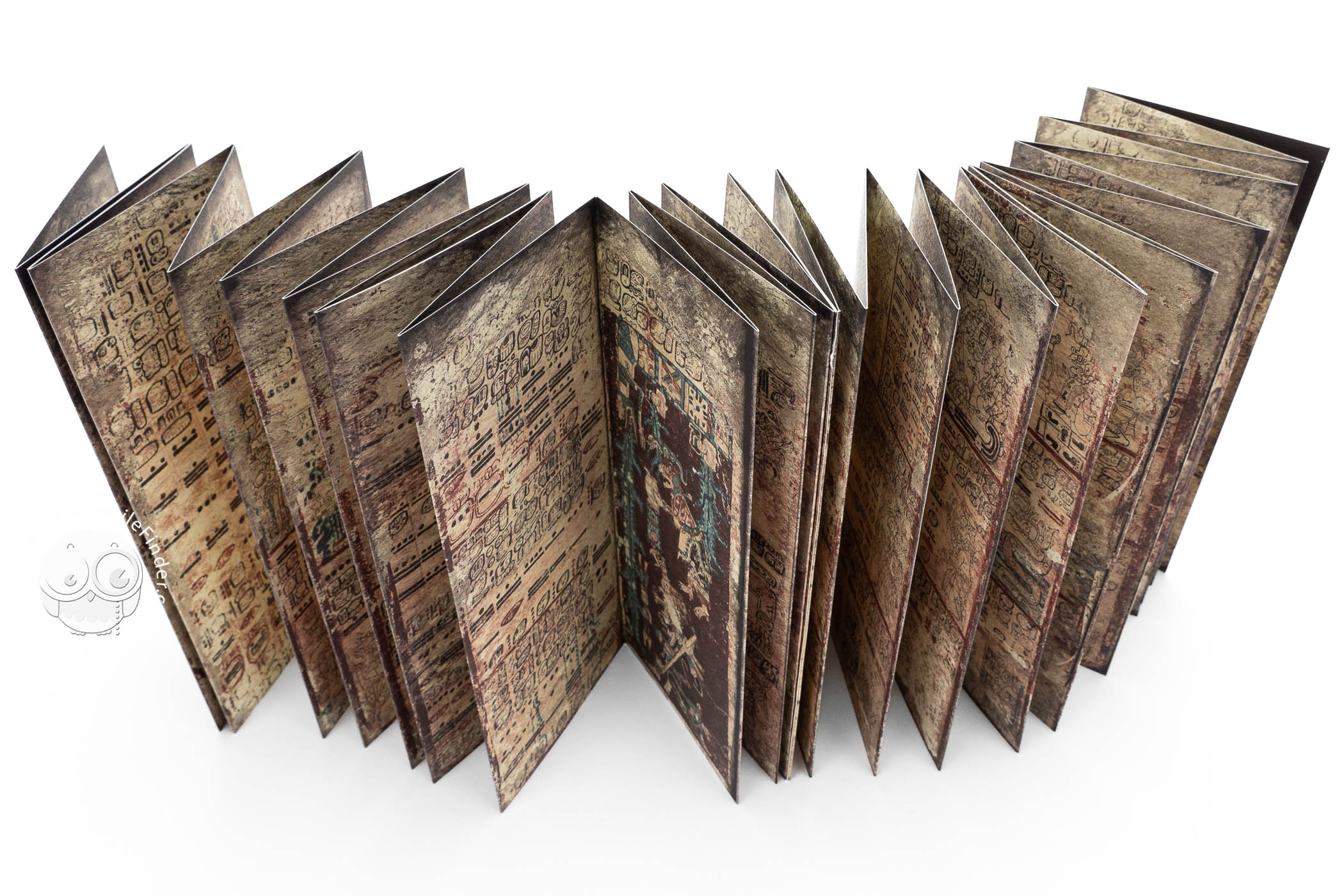

Its pages—thin sheets of fig-bark paper coated with white plaster—were covered in symbols that no one could decipher. Scholars dismissed it as a crude forgery, a suspicious artifact pulled from a cave by looters, too simple and too strange to be real.

But today, thanks to artificial intelligence and a new generation of scientific tools, the Maya Codex of Mexico has been declared authentic,

older than any other surviving Mayan book, and filled with revelations that are forcing historians to rewrite what they thought they knew about this ancient civilization.

The story begins in the 1960s, when a Mexico City collector named José Sáenz was approached by two men claiming they had discovered a secret cache of Maya relics.

They flew him blindfolded to a remote airstrip, drove him deep into the countryside, and led him into a dry cave where a folded manuscript lay beside wooden masks, sacrificial knives, and unpainted sheets of bark paper.

Sáenz bought the book, unaware that his decision would ignite one of archaeology’s most bitter, longest-running debates.

When the codex was first displayed publicly in New York in 1971 and photographed for researchers around the world, doubts erupted immediately.

It lacked the dense, intricate hieroglyphs of the famous Dresden and Madrid codices. Some drawings looked too bold, too simple, too unlike the elegant lines of classical Maya art.

Experts saw red sketch marks underneath the figures and straight edges they believed were too modern. By 1975, one of the most respected Mayanists alive declared it a fraud, and the manuscript was dismissed for decades.

After its return to Mexico in 1977, the codex disappeared into deep storage. For forty years, it lived only in photographs, fueling rumors, arguments, and quiet resentment among scholars who suspected the truth had been buried along with it.

Everything changed in the 2000s, when a new generation of researchers reopened the case with advanced tools that didn’t exist when the codex first surfaced.

A team of four experts—drawing from Brown University, Yale, and the University of California—reanalyzed every surface, pigment, and sheet fiber.

Natural mineral pigments matched materials used by the ancient Maya centuries before the Spanish conquest. The bark paper revealed its age through carbon signals that no forger could fake.

And when AI models processed thousands of chemical readings from the plaster base, the results confirmed the codex’s materials belonged to the early Postclassic era, between A.D. 1021 and 1154.

That makes it older than the Dresden Codex and the oldest surviving readable book in the Americas.

With scientific doubt erased, the manuscript could finally be examined for what it truly is: a working Maya book, created not as art but as a practical guide for priests tracking the dangerous cycle of Venus.

The codex is built around the 584-day loop of the planet’s appearances—its vanishings behind the sun, its burning return as the morning star, and its slow transition back into the evening sky.

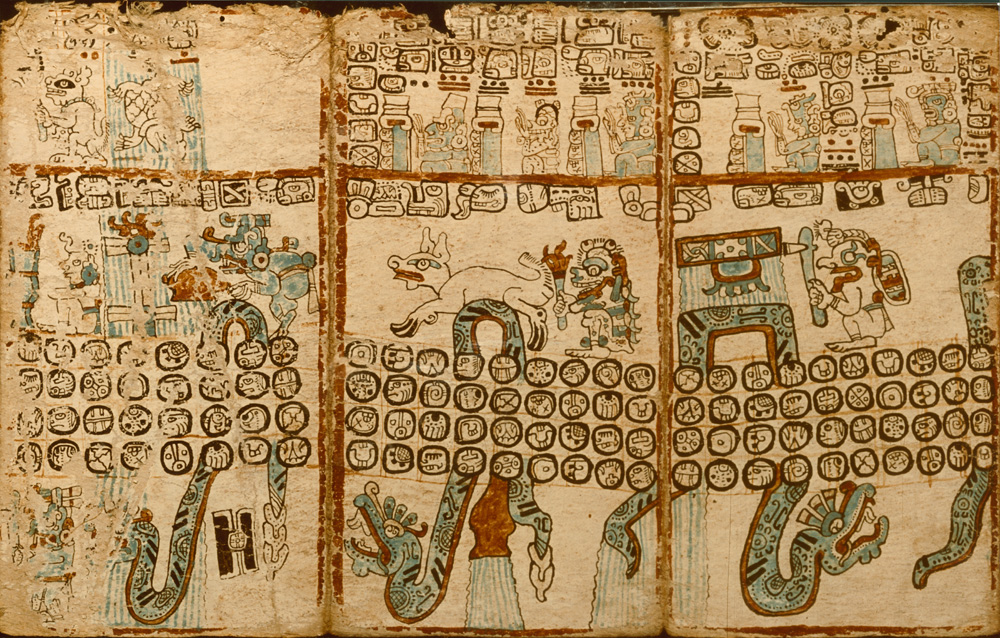

For the Maya, Venus was not a distant planet. It was a supernatural force tied to war, sacrifice, famine, and omens of cosmic significance. Each page of the codex follows a rhythmic layout.

Along one side, a vertical list of day names from the sacred 260-day ritual calendar. Across the top, circular rings containing bar-and-dot numbers that direct how far to count down the column.

At the center, the image—brutal, symbolic, unmistakably clear. Together, they indicate precisely what ritual, act, or event was expected on the corresponding day of Venus’s cycle.

Ten pages survive, each one blunt in its purpose. One shows the god K’awiil confronting a bound captive. Another depicts a death deity marking a day reserved for killing.

Elsewhere, a spear-throwing sun god launches a dart at a temple. A skeletal figure—possibly the morning star god from central Mexico—holds a severed head in one hand and a blade in the other.

These violent cycles repeat across the codex, revealing a worldview where celestial patterns dictated earthly acts, where the rise of Venus could signal war, where time itself carried danger. Other pages shift from violence to ceremony.

A god stands beside a luminous tree, an image that reflects cosmological ideas shared across Mesoamerica. On another, a bird-serpent warrior spears a temple in a scene echoing broader regional mythologies about sacred battles and divine intervention.

The manuscript’s construction confirms its authenticity just as clearly as the science behind it. The pages show cracks where plaster hardened and later split along ancient folds—breaks no modern copyist could reproduce convincingly.

Edges nibbled by insects show scalloped patterns created by centuries of organic decay, not scissors or knives. Damp stains reveal at least three separate periods of water exposure.

And the brushwork—broad strokes for day signs, fine strokes for figures—demonstrates a confidence and consistency traceable to a single trained artist.

Now authenticated, the codex joins the other three surviving Maya books that escaped destruction: the Dresden Codex in Germany, the Madrid Codex in Spain, and the Paris Codex in France. Each offers a different window into Maya thought.

Dresden, with its immaculate astronomy tables and ritual almanacs, reveals the mathematical sophistication of Maya skywatchers. Madrid serves as a priest’s handbook, filled with practical instructions on farming, weather, ceremonies, and daily life.

Paris tracks long cycles of time—k’atuns—linking each era to ruling gods, ceremonies, and predictions for the future. Together, these four codices form the last surviving library of an intellectual tradition that once filled countless bark-paper books.

Most were burned by Spanish priests during the conquest or destroyed by centuries of heat and humidity. What remains survived only through extraordinary luck.

But none of those manuscripts are as old as the Maya Codex of Mexico. And none were decoded through the tools of the modern world.

AI played a pivotal role not only in analyzing pigment composition but also in pattern-matching thousands of glyph variations, identifying subtle elements of iconography, and reconstructing parts of damaged pages where human eyes saw only cracks and stains.

As machine models processed these symbols, long-silent stories reemerged: the rhythm of Venus, the cycles of war, the cosmic fears of ancient astronomers, and the rituals that tied sky and earth together.

After decades of doubt, the manuscript briefly went on display in Mexico City in 2018, marking a triumphant conclusion to one of archaeology’s most contentious mysteries.

And yet, in many ways, this is only the beginning. The codex is now fueling new research into Maya astronomy, regional artistic influences, and the transmission of knowledge across centuries.

For historians, it is a reminder that ancient civilizations encoded far more in their books than modern scholars once believed. For AI researchers, it is proof that machine analysis can revive voices the world nearly lost.

And for the Maya themselves—whose descendants still live across Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras—it is a powerful confirmation of an intellectual legacy that endured conquest, looting, skepticism, and time itself.

News

Doomsday From the Sky: The Shocking New Timeline of the Day the Dinosaurs Were Erased

A reconstructed scientific timeline details the minute-by-minute destruction unleashed when the Chicxulub asteroid struck Earth 65 million years ago. …

Descubrimiento de una Civilización Perdida Bajo Angkor Wat: Un Enigma Científico

A vast urban network buried beneath Angkor Wat has been revealed through LiDAR and radar imaging, uncovering roads, canals, reservoirs,…

Palace Denies Prince Harry Informed Them About Canada Trip, but His Team Says He Did

Prince Harry traveled to Canada for Remembrance Day events, surprising Buckingham Palace aides despite his team claiming they informed them….

Exiled and Exposed! Former Prince Andrew Spotted Riding Alone at Windsor as Royal Titles Erased and Falklands Honors Vanish!

Former Prince Andrew was spotted horseback riding at Windsor Castle for the first time since losing his royal titles and…

BBC Issues Rare Apology to Kate Middleton After Remembrance Broadcast Backlash

The network received criticism over the Princess of Wales’ titles after covering the royal family’s Remembrance tributes In…

Wall Street in ‘extreme fear’ as stocks plunge AGAIN amid fears world’s biggest company is a dud

Wall Street suffered another sharp sell-off as major indexes and Bitcoin extended their steep November declines. Investors are gripped by…

End of content

No more pages to load