Here’s the thing about Sissy Spacek: the legend isn’t loud. It never was. She’s not a torch aimed at the sky, demanding attention. She’s a pilot light—steady, precise, honest enough to make the audience lean in. And at 75, with more winters behind her than ahead, the story isn’t about downfall or scandal. It’s about endurance. It’s about the cost of telling the truth on camera and choosing a quieter truth off it.

Spacek’s biography reads like a long walk through two Americas—small-town Texas with its cedar-scented evenings and reluctant tenderness, and Manhattan’s winter bite where softness gets tested. She was a Christmas baby from Quitman, the kind of childhood that convinces you gentleness is a viable plan. By 1967 she’s in New York with a guitar and a stage name (Rainbow), trying out the city’s indifference. The modeling gigs and one-line auditions didn’t look glamorous from the inside. Survival rarely does. She kept at it. She learned to strip the layers at the Actors Studio until what remained was simple: truth or nothing.

The ignition didn’t arrive with a miracle headline. It showed up as Terrence Malick’s Badlands in 1973—Spacek’s stillness creating a strange gravity, her innocence with a seam of danger. Then came Carrie in 1976, a modest-budget horror film that turned into a cultural shockwave. Her audition wasn’t costume; it was an argument for reality. She wore a childhood dress, drained the vanity from her face, and played humiliation as if it were a living thing—quiet, sticky, impossible to shake. She let the prom dress rot and harden over days of filming. She sank. She rose. And audiences believed. The Oscar nomination was less an arrival than a confirmation: here is an actor who will not lie to you.

Cole Miner’s Daughter closed the case. Loretta Lynn wanted Spacek, and Spacek earned the vote every mile—shadowing, singing, refusing prosthetics, embodying rather than impersonating. The transformation didn’t have the shine most actors chase. It had the integrity they can’t fake. She won the Oscar. Then kept opting for roles where spectacle wasn’t the point. Missing. The River. Crimes of the Heart. In the Bedroom. Performances that smoldered, not screamed. If you’ve ever sat through an awards season with your patience intact, you know how rare that is.

But the career is only one thread. The life is the fabric. Spacek met Jack Fisk on Badlands, married him in jeans with a dog as witness, then did the most unpopular smart thing a rising star can do: she left. Not forever, but for long enough to build something that wouldn’t collapse under applause. They moved to a horse farm in Virginia—210 acres of deliberate pace. Studios called it career sabotage. Spacek called it oxygen. Children arrived. Money wasn’t always friendly. Work was chosen, not chased. The farm, the mornings, the rhythm. If you’re allergic to sentiment, fine. But do the math: the long marriage, the daughters who grew up with fence lines and not paparazzi, the work that stayed selective and strong. That’s not retreat. That’s curation.

Grief threads through the story like a low note. Her brother Robbie died at 18, the kind of early loss that teaches you how long absence can hum inside a person. Later came her mother, then her father, each departure reshaping the emotional map she drew from onscreen. And then Loretta Lynn—the friend, the witness, the woman who understood Spacek from the inside. The world got a national mourning; Spacek lost a private compass. If you’ve ever carried a friendship that made a career livable, you don’t need me to explain the scale.

It’s tempting to read tragedy into every quiet life Hollywood can’t locate on a GPS. Don’t. Spacek didn’t sour into a recluse. She aged into someone who uses time well. The farm remains her best defense against the modern impulse to perform happiness. Her days look like work and calm and a kind of health that doesn’t demand you believe in miracles—real food, real rest, actual silence. The net worth headlines are the least interesting angle except as a footnote to the central argument: she built a life by choosing the human over the brand, the long over the loud.

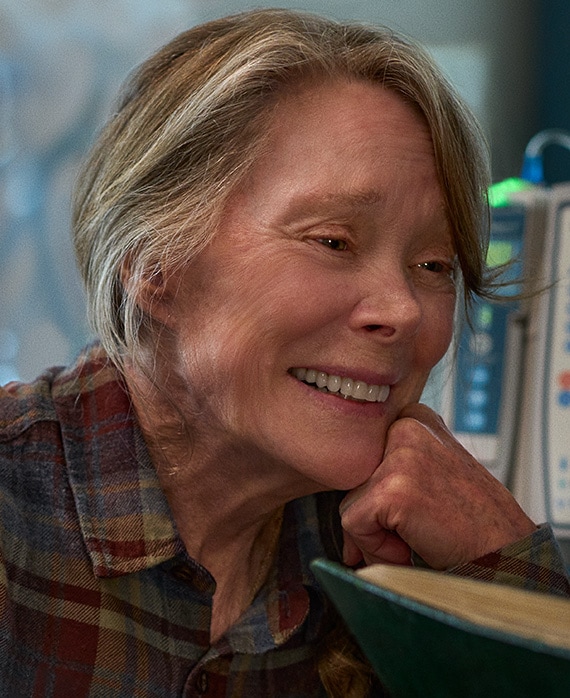

If you want the anatomy of her power, start with the face. Not just the features—what she lets pass through them. Rage without noise. Grief without collapse. Love without sugar. She doesn’t play notes; she plays breath. Directors who know the difference trust her with the parts other actors over-decorate. She returns them stripped, polished by restraint.

Here’s a small skepticism worth mentioning: we have a cultural habit of confusing endurance with martyrdom, especially with women who refused to turn their lives into campaigns. Spacek did not renounce ambition. She repurposed it. She aimed it at the work and the family and the land. She measured success by integrity and the absence of regret. That’s unfashionable. That’s also the point.

I’m not sure we talk enough about the witness factor—how crucial it is to have someone who saw you before the world did. Fisk qualifies. Lynn did, emphatically. After those witnesses are gone, the job of memory gets heavier. Spacek carries it lightly, or at least without performance. The photo on the desk. The music in the kitchen. The walk at dawn with dogs along a fence line. If that sounds small to you, you might be listening for the wrong frequency.

So no, the tragedy of Sissy Spacek is not in flames or ruin. It’s in the quiet arithmetic of a life counted in losses and chosen limits, and what she made inside that margin. The films remain. The farm remains. The marriage remains. The craft remains—this insistent belief that truth, even whispered, carries farther than a shout.

We could use more of that—less brand, more breath. Spacek’s legacy isn’t merely the roles; it’s the terms. Do the work. Tell the truth. Refuse the circus. Build a home where the applause can’t touch you. And when grief comes—and it will—let it deepen the story rather than end it. That’s not heartbreaking. That’s instructive. That’s a life.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load