Before Death, Diana Keene Finally Opens Up About Her Two Wild Children — A Fictional Confession

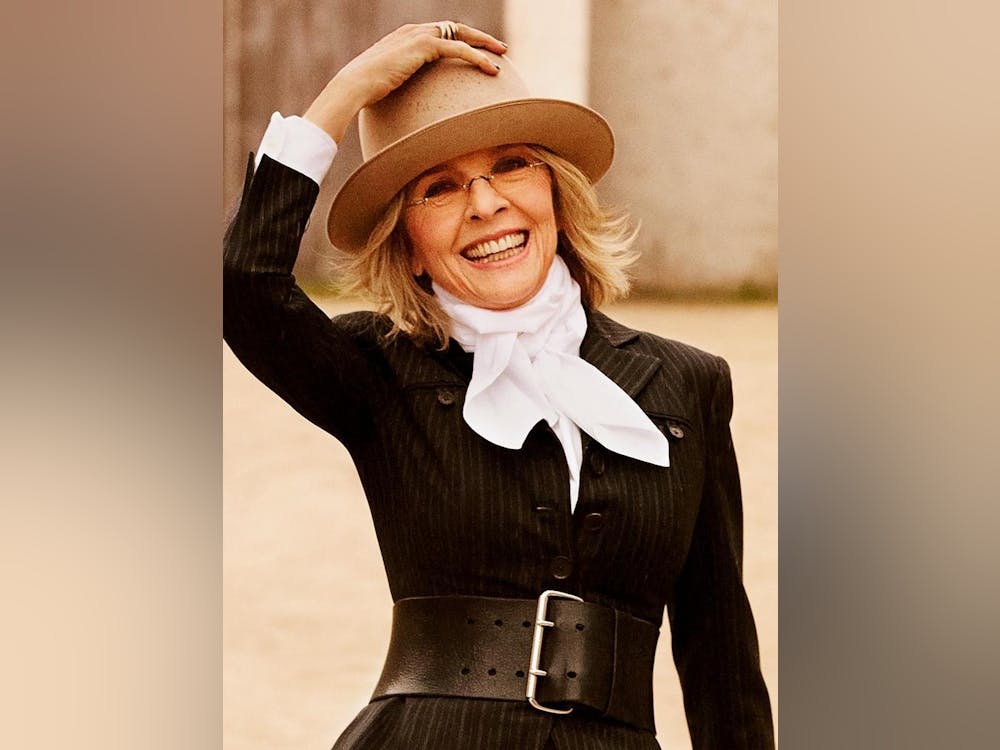

She had always been a woman who arrived late and lit up the room. Photographers learned the rhythm of her entrances, magazine editors learned the cadence of her interviews, and a generation of actresses learned that eccentricity could be a brand. Diana Keene — Oscar winner, fashion icon for hats, the woman who had once made an audience laugh and then weep with a sideways glance — lived a public life that most people mistook for a whole life. Fame is a good disguise. It teaches people to applaud what is visible and ignore what is not.

When Diana began to speak candidly, in the filtered light of her Beverly Hills study, people expected gossip. They were not ready for the confession she gave instead: an exhausted, honest reckoning about motherhood, absence, regret, and the stubborn hope for grace. She was eighty in the spring she signed the document that everyone misread as her last vanity — a will, yes, but also a ledger of love, ledgered not by dollar signs but by small, precise gestures. She left everything, she said, except regret.

This is fiction. The name is invented, and so are the intimate details that follow. But the feelings — the ache of being both adored and alone, the ruins of good intentions, the tender bargains between parent and child — are familiar to anyone who has ever loved in public and parented in private.

Diana’s life read like one of her films: scenes of dazzling success interspersed with moments of quiet defeat. Born into an ordinary house, she learned early that the world noticed some people more than others. She learned how to stand still and be liked. The camera taught her posture, conversation taught her wit, and the theater taught her the safer substitute for genuine presence — rehearsal. Success followed, and with it a busier schedule, a ledger of awards, and a public identity that demanded maintenance. What she did not anticipate, or perhaps refused to see, was how those long rehearsals for the rest of her life would complicate the private work of raising children.

At fifty, when most people were supposed to be settling into the roles they had chosen, Diana chose something different: two adoptions that altered the axis of her days. Dexter — the elder, quiet and watchful — arrived first. Duke — the younger, fierce and mercurial — arrived two years later. Both were small and raw and untroubled by the celebrity that clung to their mother like the tail of a dress. For Diana, the adoptions were a deliberate act of reclamation: she would create, with her hands and voice and stubborn love, a private world immune to the camera’s glare.

That world lasted just as long as worlds tend to last under the weather of public life: long enough to fall desperately in love, and not long enough to be kept safe. Diana juggled nights on set with mornings of math homework; phone calls with newborn cries; interviews that required a practiced melancholy and school meetings that required a real presence she increasingly could not find. The rhythms of filming — wrap, fly, repeat — did not pause for piano recitals or scraped knees. When a script called for tenderness, Diana found it. When life demanded it, she sometimes did not.

The children, of course, noticed. They noticed the empty chair in the audience at the school play; they noticed the long evenings when a mother’s laugh came from somewhere the television had left behind. They learned the language of compromise early: that public adoration could be a substitute for attention, that the red carpet sometimes swallowed the day.

Dexter grew inward; she guarded her feelings the way some people guard language. She learned to find solace in books and the steady discipline of the piano bench. Where Diana’s life offered spectacle, Dexter sought refuge in the small, ordinary acts of practice — scales at dawn, the slow stitch of notes into a song. Duke moved the other way: loud, combustible, an instinctive rebel who wanted proof that affection was not a transaction. He tested the boundaries of a home that was sometimes absent, seeking through mischief to elicit a presence that performance often deferred.

If the story of many families is a slow unravelling, Diana’s had a few dramatic unspoolings — slamming doors, a teenager who walked out with a backpack and the composure of someone making a decision that would be decisive in her mother’s life. The first bitter, unforgettable phrase hit Diana like a private laceration: “You work for you.” It was said once in a kitchen that reeked of equally mixed emotions: dinner cooling on a plate, silence threaded into the air. For Diana, the words were less accusation than mirror; she realized, in the long quiet following them, that she had built a life in which absence often came for reasons she once called duty.

Time does not always work like a slow, pedagogical teacher. Sometimes it teaches with blunt force — a sudden hospital stay, a headline, an award speech where the applause does not feel like the balm it once was. It takes a kind of cruelty to be famous and old: your image outlives your energy, and people prefer photographs to apologies. Diana learned to trade in tokens of presence instead. When she could not be there, she left gifts: a house here, a photograph collection there, a piano for one child who still loved to press keys and find a melody.

The will she composed late in life is less a legal instrument than an attempt to speak to the children who had at times been strangers. She divided material things unevenly on purpose — one house to Dexter, a portfolio and the piano to Duke — but the carefulness of the distribution was not about fairness. It was about acknowledging who each child needed her to be in the only language she had left: practical tenderness. To Dexter, she left the archivist’s inheritance, all the photographs she had taken of small unremarkable things: the chipped mug, the backyard apple tree, the face that had once looked at her with quiet trust. These were the objects that, more than trophies, speak of a life shared. To Duke, she left the piano and whatever money would allow him the freedom to fail and to travel without the pressure of an immediate paycheck. It was an economic translation of an emotional wager: release in funds, memory in prints.

People who are not parents think that a will is about money; for many parents, a will is a final letter. Diana insisted on both. She asked her lawyer to place messages inside the boxes: postcards of apology, little notes explaining choices, and one folded sheet that read in plain script — “I loved you badly and well; forgive me; keep my hats.”

The process of reconciliation is uneven. Sometimes a quiet return is all a parent can hope for: an old daughter who shows up at the hospital with flowers, an estranged son who sits on the bedside and breathes, too shy for many words but present all the more for it. Those are the tender scenes that make the most ordinary human headlines: small reconciliations that do not erase the past but soften it. Diana had such nights. She had, in the end, a handful of dinners that tasted of ordinary mercies. Her children came and sometimes stayed for a while; sometimes left again. They lived in the dynamic tension that forms when love is both imperfect and persistent.

Diana’s frailty did not render her tender only in the way the movies like to portray. She was stubborn to the last; she wanted to shape the terms of her legacy and, by doing so, to remind her children how she had thought of them. Her foundation — the Keene Light Fund in the will — was set up to help aging artists and single mothers. That detail reveals something practical and humane about an actress who had spent her life working in an industry that so often forgets the people behind the lights. She wanted to leave not merely wealth but a pattern of attention: small stipends for the people who had nowhere else to go, money for piano lessons for children in the arts, grants for actresses who had aged out of the casting pool but still needed medical care. It was a moral architecture aimed at making her own end meaningful beyond the private household.

The public’s appetite for scandal made the headlines about Diana’s will louder than they needed to be. People rearrange themselves around celebrity confessions like weather; the internet asked for a villain, for a neat narrative about fame and neglect, about mothers who “chose career over kids.” But the truth, always a more unglamorous thing, resisted tidy arcs. Her life was not a morality play. It was a messy ledger where some entries balanced and others did not.

Those who had known Diana in her younger days told stories of an eccentric, luminous woman who could charm a room and then slip out and sit on a curb to watch the city breathe. She could be loving, and clumsy. She could hold the moment and still miss the point. Her talent made her public; her mistakes kept her human. In the final months, the friends who stayed told a new story: of a woman who had unlearned vanity and learned instead small acts of contrition. She baked cookies and left the pan on the stoop of the neighbor who had helped her forty years earlier. She wrote letters she never sent to friends who had drifted away. She told the same story to her nurse twice in one day, each time with different emphasis and the same laughter at the end.

What remains after such a life is not the tabloidable scandal but the quieter proofs: a piano that plays when no one watches; a house with fingerprints in its dust; photographs that retain the exact tilt of a child’s head. The public will scroll past these details because they lack the high voltage of gossip. But the people who were there — the kids, the neighbors, the friend with a key — keep them. They are the real archive.

The fiction of Diana Keene’s closing chapter matters because it stitches a pattern readers recognize: that fame does not inoculate against ordinary heartbreak, and that public performance can obscure the private labor of care. It is a small parable about the cost of being admired and the price of being absent. It’s a warning and a consolation both: that we can do better, that we can forgive, and that the final ledger of a life is not always the accounting of what was accumulated but what was returned.

In her final letter to her children — the one placed into the will in a thin envelope — she wrote: “I have been a performer in many stages of life. The only thing I finally learned is that being a mother is not a role with a script you can memorize. It’s a daily decision to show up. I did not always show up enough. I am sorry. I am proud. I love you both in ways that will not fit an obituary. Keep the music. Keep the photos. Keep one another.”

The children read the note in private. Outside, the paparazzi were predictably disappointed: no last confession to defame, no final scandal. Instead, something smaller and more complex had happened: a mother’s attempt to pay attention late in life, couched in the clumsy grammar of late apologies.

And then the performance ended in the way all performances do — with a quiet exit. Friends who visited in her last days said that she smiled more than she had in years. She folded the world down to a manageable size: a bowl of fruit, a sunlit chair, the sound of a piano humming from downstairs. She took the last pen strokes seriously — the final act of a life that had always loved an audience — and for once aimed the words at a family rather than a crowd.

If there is a final lesson in a story like Diana Keene’s, fictional though it is, it is this: fame amasses, but it does not substitute for the small routines that bind people — listening at the kitchen table, returning a phone call, sitting through a recital even when the lighting call is the next morning. Public glory is a thin veneer over private negligence, but it can be repaired in slivers if people choose to repair it. The ledger she left, the piano, the photographs, the money for single mothers and aging actresses — these are not tidy absolutions. They are an attempt at restitution, offered in the honest currency of attention.

In the end, the photograph that her children kept after the funeral is not a studio shot. It is a candid: Diana in a faded sweater, hair loose, eyes soft as a dusk. She is neither perfect nor a villain. She is merely human — late, luminous, fallible, and finally, in small ways, returned.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load