Here’s the problem with legends: they age better than people. The story is cleaner, the motives are sharper, and the endings—especially in Egypt—prefer knives over medicine. For years, Queen Hatshepsut’s death sat under that old shadow: the brilliant female pharaoh, undone by her ambitious stepson Thutmose III. It was tidy, dramatic, satisfying in a way only palace intrigue can be. And then the lab machines got better, the questions got blunter, and the truth rolled in like desert heat—slow, relentless, impossible to ignore.

What the latest forensic work suggests is not murder, not even a good conspiracy. It’s biology and bad luck, the kind that doesn’t care how many obelisks you raise or how well you manage a treasury. A team led by Egyptologist Zahi Hawass took another run at a mummy long associated with Hatshepsut—KV60A—and did what scientists do when the old stories stop holding: they checked. Modern imaging. Chemical analysis. 3D reconstructions that would’ve been science fiction a decade ago. Out came a profile that reads like a physician’s grim clipboard rather than a scribe’s accusation: morbid obesity, markers consistent with type 2 diabetes, and unmistakable evidence of metastatic bone cancer. No skullduggery. No assassin’s calling card. Just a body losing a war it never chose.

Here’s where the tale shifts from tragic to strange. Among the funerary items, researchers found an alabaster vial. For ages, it sat in the “probably perfume” category—the kind of comforting assumption museums are built on. New testing said otherwise: traces of benzopyrene, a carcinogen modern life associates with tar, smoke, soot. Imagine the queen applying a balm meant to soothe a skin condition—religious, medicinal, both—and every application quietly dosing her with toxicity. The product was ancient. The effect was modern. In trying to heal herself, she may have fed the disease that killed her. History prefers villains. Chemistry votes for indifference.

I know what you’re thinking: doesn’t this let Thutmose III off the hook a little too neatly? The later defacement of her images, the political scrub—wasn’t that a murder cover story? The timeline refuses that reading. Much of the erasure happens decades after her death, when the young stepson turned seasoned king needed the past to look straightforward. His motives read less like a crime scene and more like branding. Dynastic legitimacy requires flat narratives. Hatshepsut was anything but flat.

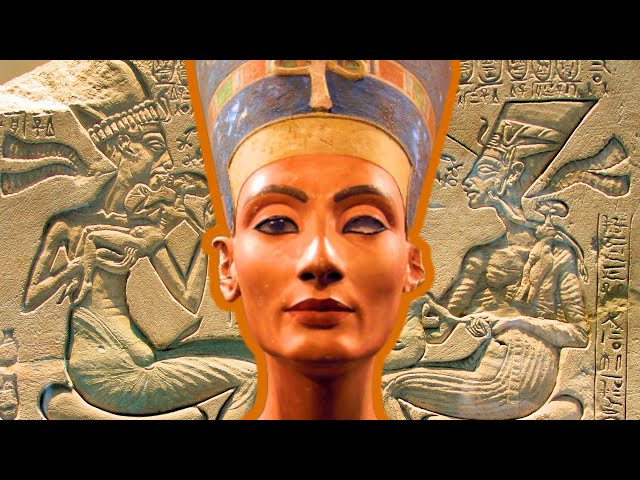

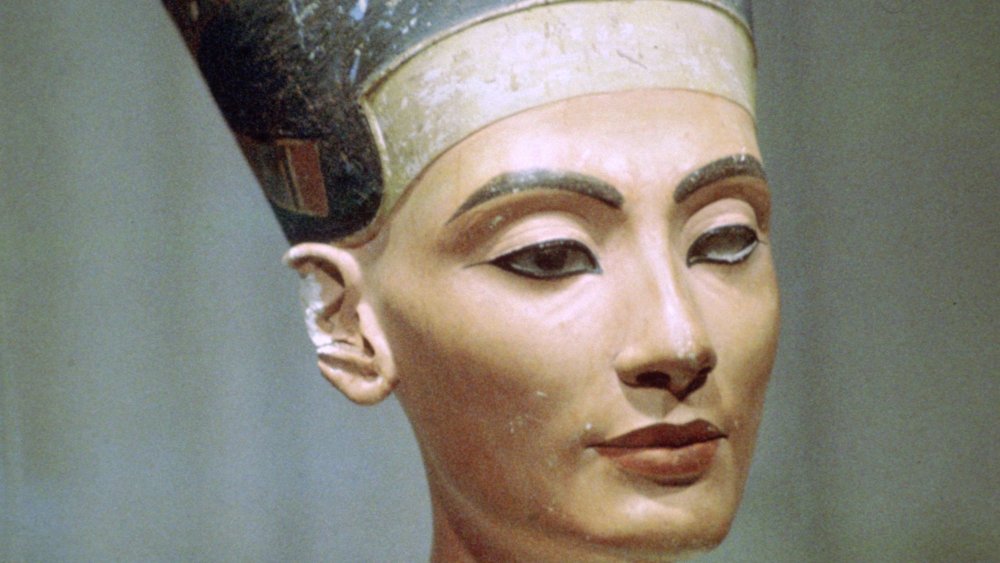

Strip the myths and she’s still astonishing. A woman who didn’t just rule but crowed herself king, who built at a scale that still shames the surrounding silence, who understood trade like an economist and ritual like a priest. Her reign reconfigured Egypt’s confidence—architecture as argument, authority as craft. That she was brilliant is not in dispute. That her body betrayed her is now, painfully, beyond speculation.

The hard truth—and the reason this new science matters beyond the headlines—is that it humanizes a figure we’ve mostly encountered in stone. Disease has no respect for power. It doesn’t check the cartouche or the crown. The image of Hatshepsut in her final years, fighting not enemies but symptoms, is not a diminution of her legacy; it’s a recalibration. The agony of metastatic cancer, layered on top of metabolic strain, turns every step into labor. Add the possibility of self-poisoning through an ointment meant to help, and you have a portrait of a ruler caught in a somber bind: doing the reasonable thing and paying the unreasonable price.

There’s a larger question humming under this. If Hatshepsut’s balm carried carcinogens, what else were ancient elites using that did harm quietly, incrementally? We’ve always romanticized the perfumes, the unguents, the painted rituals of the court. The same chemistry that makes a sauce taste divine can make a medicine dangerous. Ancient pharmacology was experimental, sacred, and largely unregulated. The idea that a queen could be touched by industrial-grade risk from a devotional routine is not poetry—it’s precedent.

And yet the public hungers for villains. Not because we’re cruel, but because causality feels better with a face. Thutmose III is easy to cast. He’s male, adjacent to power, ambitious. The later erasures look ugly. But scholar after scholar has been nudging the narrative for years: those actions read like politics, not panic. When kings rewrite history, they’re not hiding a body; they’re simplifying a lineage. We do versions of this now—corporate rebrands, institutional “refreshes,” textbooks that flatten rough edges. The ancient court just did it in stone.

What we gain from letting the murder plot go is not pity; it’s perspective. Hatshepsut’s life was a defiance of expectation. Her death, as the evidence now stacks, was a collision with the limits of the flesh. This doesn’t make the story smaller. It makes it closer. Consider the administrative competence it takes to manage a kingdom while enduring chronic disease. Consider the daily calculus: how to maintain ritual, project stability, delegate wisely, and still find room for pain. The legend of her rule suggests she did more than endure; she executed—temples, trade routes, a bureaucracy that could outlast weather. The body under that crown was breaking. The work did not pause.

If you’ve spent time with archaeologists, they’ll tell you: the sand is patient. It keeps what we drop and returns it only when asked properly. This round of asking—CT scans, chromatography, material science—does more than solve a whodunit. It asks how a civilization treated the bodies of its rulers and what those treatments cost. For a long time, we imagined pharaohs as a separate species. That fantasy is useful when you want to explain a 97-foot obelisk. It’s less helpful when you need to understand death. The benzopyrene in that alabaster jar makes Hatshepsut legible not as myth, but as a patient.

Skepticism still belongs in the room. The identification of KV60A as Hatshepsut, while broadly accepted, rides on a chain of inference and comparative data. Ancient balms vary wildly; a carcinogenic signal in one sample doesn’t certify every jar. And correlation is not causation—metastatic cancer has many doors. But the weight of the profile, taken together, is persuasive. It’s not hard to imagine the queen’s physicians—priests in white—doing their best within the limits of the day, trusting ritual and recipe, and missing the hidden cost. We do this now, with better instruments and different blind spots.

The politics will get rewritten, too. If Hatshepsut didn’t die by intrigue, then Thutmose III’s later campaign against her memory reads like consolidation rather than confession. He needed a narrative with fewer contradictions. A woman ruling as king was a miracle and a problem. When miracles end, problems remain. Stone responds well to chisels.

The legacy, though, remains granite. Hatshepsut’s buildings don’t care about our latest op-ed. Deir el-Bahri still stages sunlight like theatre. The obelisks still point past us. The story this new science tells—of a ruler whose mind outpaced her body—is the one that survives most honestly. Power does not inoculate. Glory does not anesthetize. The human thing, old as dust, is to keep working until the day says stop.

So yes, “She wasn’t murdered” makes a good headline. It’s corrective, punchy, cinematic in its own right. But the deeper news is slower: ancient lives break for reasons as mundane and brutal as ours. A queen can be undone by the chemistry of her own cure. A dynasty can reshape memory for pragmatic reasons rather than guilty ones. And the desert will continue to deliver evidence that makes our favorite myths blink and step aside.

What’s left, when the shock fades, is respect. Not for invincibility—that’s the child’s version—but for a kind of resilience that builds in stone while carrying pain in silence. Hatshepsut earned the monuments. She also earned a human ending. We can hold both. The legend of the woman who called herself king doesn’t require a dagger. It stands, taller and more honest, on the truth that even the most audacious ruler lived in a body, and that the body writes the last chapter.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load