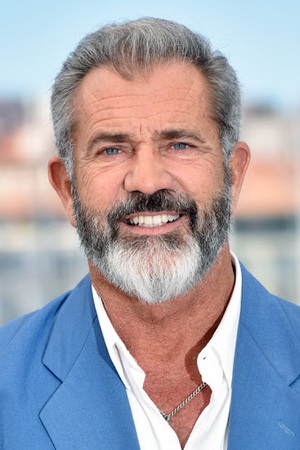

Here’s the thing about miracles on movie sets: they make great copy and terrible evidence. The Passion of the Christ has carried two parallel reputations since 2004—an R-rated juggernaut that rewired Hollywood’s assumptions about faith audiences, and a magnet for stories that sound like campfire theology passed down by grips and gaffers. Mel Gibson’s recent refrain—“To this day, no one can explain it”—lands somewhere between confession and branding. Still, the production did leave footprints that are hard to ignore: a star struck by lightning, a set that felt haunted, conversions in the craft services line, and a box office that preached louder than any studio memo.

Start with the vision. Gibson wasn’t playing the usual studio game. He went inward—back to Catholic roots, the Gospels, and the charged mysticism of Anne Catherine Emmerich—and came out with a plan most executives would hide under a pastry cart: shoot the crucifixion in Aramaic, Latin, and Hebrew; no marquee names; no soft focus. The idea was simple in the way dangerous ideas often are—strip away modernity and theater, ask audiences to sit with pain. When every major studio passed, Gibson mortgaged himself: roughly $30 million for production, $15 million for marketing. In a business that loves prudent risk, that’s a public vow.

Casting followed the same logic. Jim Caviezel—devout, serious, relatively un-famous—said yes knowing a role like this sticks to you. The numerology around him (JC initials, age 33) is the kind of detail that preachers and publicists both enjoy. Whether it means anything depends on your appetite for patterns. On set in Matera, Italy—the stones practically biblical—the atmosphere got strange. Crews described mood whiplash and sudden tears during the heavy sequences. Weather turned on a dime. Equipment failed in ways that felt personal. More than one person stepped off the set to pray, which isn’t unheard of in difficult shoots, but the volume of it was.

Then there’s the lightning, the anecdote that refuses to retire. Caviezel has described being struck on the cross, tongue bitten, later cardiac complications. An assistant director reportedly got hit as well—twice. “Statistically impossible” makes headlines; statistically unlikely is closer to the truth. But the human reality is blunt: a metal rig, exposure, cold, fatigue—all can stew into danger. In the scourging sequence, the whip caught flesh. Shoulders dislocated under the weight of the cross. Hypothermia set in. Sometimes the screams weren’t performance; they were triage. Anyone who’s spent time on sets knows the line between method and misery is easy to cross when the schedule won’t blink.

The spiritual fallout is harder to quantify and easier to narrate. Luca Lionello, who played Judas, moved from atheism to Christianity post-production. Other crew members reported nightmares, fevers, an insomnia that rode them for weeks. Some found baptisms. Some found silence. Not everyone who lives through something intense wants to perform their testimony in public. Whether that silence implies the supernatural or just respect for complicated experiences depends on the listener.

The release strategy was a quiet masterclass. Gibson bypassed the usual marketing labyrinth and went straight to churches—pastors as ambassadors, screenings as liturgy. Ash Wednesday, 2004, the film opened like a ritual. $23.5 million day one. $83.8 million weekend. $611 million worldwide. It became the highest-grossing R-rated film to that point not by courting controversy—though it had plenty—but by uniting an audience that had felt patronized or ignored by Hollywood. The violence was argued over, the portrayal of Jews was condemned by many Jewish organizations as historically dangerous, and emergency rooms reported faintings that became their own mini-myths. Yet for millions, the film functioned as devotion, shock therapy, and identity statement rolled into one.

After the triumph came the toll. Caviezel’s mainstream career cooled—blacklist talk swirled, and while Hollywood seldom prints its biases, it does enforce them. He leaned into faith-forward projects and public witness; regret never made his statements. Gibson’s aftermath was uglier. The 2006 DUI, the anti-Semitic tirade, the recordings—public sins that didn’t need supernatural explanations, though some people offered them anyway. “Spiritual warfare” is a tidy frame if you’re inclined toward theology; the industry offers a grimmer one: fame amplifies what’s already there, and scandal eats careers for breakfast.

So what do we make of the “no one can explain it” thesis? Some parts have explanations. Lightning hits people; rare, but not magic. Cold weather injures actors; ask anyone who’s done a winter shoot in period costumes. Emotional responses to intense material are predictable in the same way stadium tears are. The conversions belong to those who claim them; cynicism doesn’t have a monopoly on truth. The silence, the parts people won’t discuss—that’s where the story keeps its mystery. Not necessarily because of hidden demons, but because some experiences refuse to be flattened into press-ready cause and effect.

The film’s legacy is unambiguous in one area: it changed the market. It told studios, with a sledgehammer, that faith audiences could mobilize at scale and didn’t need Hollywood’s accent to feel seen. It sparked a wave of faith-based films—some earnest, some opportunistic—and gave religious leaders a case study in cultural influence. It also reopened old wounds about representation, responsibility, and the thin line between reverence and harm.

If you want the clean headline—“Mel Gibson Went Too Far and the Universe Pushed Back”—you can have it. It reads well. But the truth is stubbornly human. A director in crisis threw himself at a sacred story with a level of conviction that made the ground shake. A cast and crew shouldered a production that asked more of their bodies and spirits than most films do. Audiences arrived by the busload, some left converted, some disturbed, some angry. And the people at the center paid a price, professional and personal, that is easier to mythologize than to live.

Maybe that’s the enduring tension with The Passion. It’s both movie and mirror. It reflects what viewers bring to it—a faith that feels vindicated, a fear of propaganda, a need for catharsis, a case study in exploitation. The unexplained pieces remain, as they often do, in the spaces where art, belief, and suffering overlap. Gibson calls it inexplicable. I call it exactly what happens when you take a story that millions consider sacred and force it through the machinery of spectacle with absolute seriousness. Things move. People change. Weather misbehaves. And a set becomes, for a brief, bruising stretch of time, a place where the line between ritual and cinema gets thinner than anyone expected.

You don’t have to believe in lightning as a message to understand why this film still rattles doors. You only have to watch its reach, its aftermath, and the way even its defenders speak—softly, carefully, sometimes not at all. Some stories resist closure. This one was built to.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load