A federal judge in Washington, D.C., has reopened a criminal contempt probe that reaches straight into the upper ranks of the Justice Department and the Trump administration. The case centers on whether government officials willfully disobeyed a district-court order to stop deportation flights under the rarely used Alien Enemies Act — and on a whistleblower’s explosive allegation that a senior DOJ official told career prosecutors they might need to tell a federal court “fuck you” if a judge tried to block the removals. The legal and political stakes are enormous: the inquiry probes not only a single decision about flights and removals, but the boundaries of executive power, the integrity of the rule of law, and whether top Justice Department officials can be criminally accountable for actions taken in the name of national policy.

This article lays out the contours of the reopened proceeding, the whistleblower disclosure that helped revive it, the answers (or nonanswers) offered at a high-profile confirmation hearing, and what the renewed contempt inquiry could mean for the department and the country.

The short version: planes left, a federal judge said the government ignored his order, and a whistleblower says senior DOJ leadership told line lawyers to “tell the courts” to go to hell

On March 15, 2025, the administration invoked the Alien Enemies Act — an 18th-century statute that allows extraordinary wartime removals — to justify the rapid expulsion of scores of Venezuelan nationals the government characterized as members of a transnational criminal organization. A group of those detained sued, and a federal judge in D.C. moved quickly to halt removals long enough for a court to hear whether the proclamation and its implementation violated law and due process. In the wake of emergency filings, the judge issued orders intended to preserve the status quo and, according to court records, instructed government lawyers at an emergency hearing to return people who were in transit. Despite that, flights carrying people subject to removal took off and landed in El Salvador.

Within weeks the district judge — James E. Boasberg — found probable cause to believe government officials had committed criminal contempt for disregarding his orders. That probable-cause finding was extraordinary and rare: criminal contempt carries the possibility of prosecution, fines, and even imprisonment, and judges invoke it sparingly because of separation-of-powers concerns. An initial appellate decision trimmed or vacated aspects of that finding, but more recently a larger panel of the D.C. Circuit cleared the way for the district court to resume its fact-finding and contempt proceedings. With the appeal path now narrowed, Boasberg has signaled he intends to press ahead and hear witnesses who might explain why the government did what it did.

Why the whistleblower matter is the match that reignited the file

What made the situation combustible was a June whistleblower disclosure filed by Erez Reuveni, a long-time department lawyer who says he witnessed internal meetings in which the department’s senior leadership discussed the planned mass removals. Reuveni’s protected disclosure contains multiple allegations about how officials handled legal objections, communications with other agencies, and how they advised department litigators to respond to court interventions. Most explosively, Reuveni says that Emil Bove — then a senior Justice Department official and later a Trump appellate judicial nominee — told attendees that the deportation flights “need to take off, no matter what,” and that if courts tried to block them, the department “may have to consider telling that court, ‘fuck you.’” Reuveni says he objected and refused to sign briefs he believed were false; he was later fired.

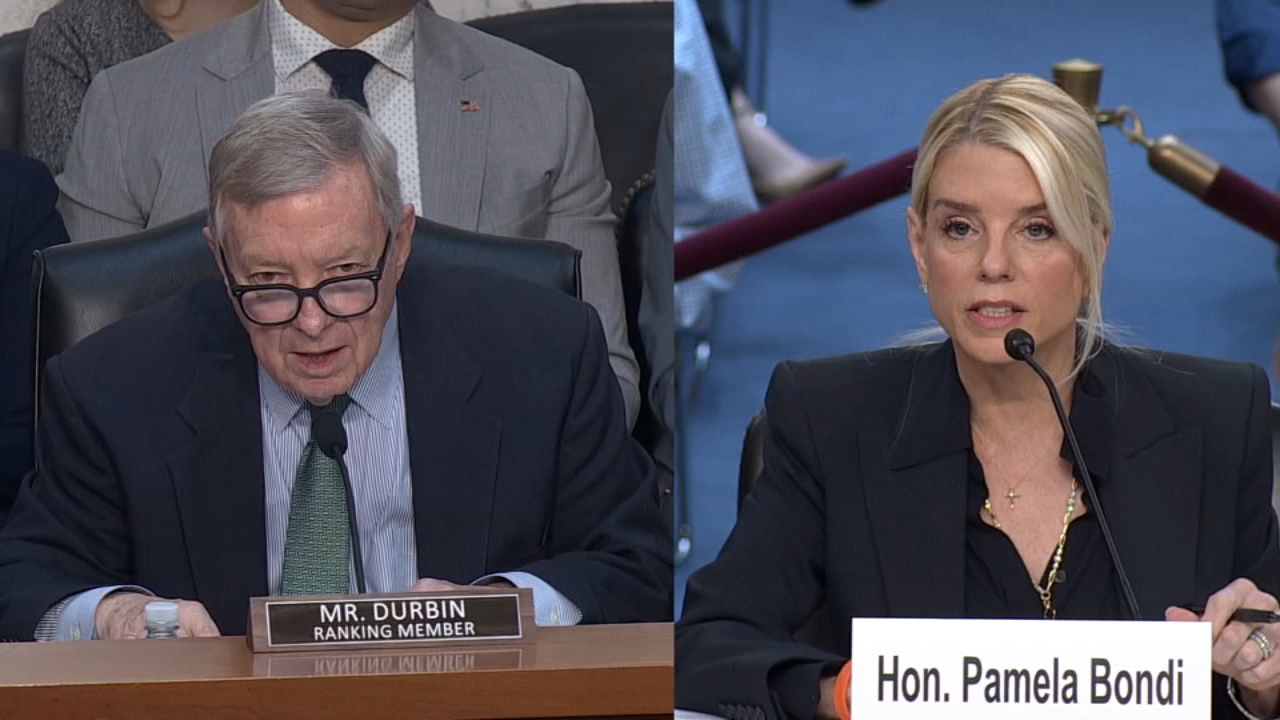

That phrase — crude, inflammatory, and direct — jumped from an internal memo into the public record and into the confirmation hearing transcripts when Senator Adam Schiff pressed Bove on whether he had used those words. Bove’s answer was evasive: he said he had “no recollection,” while insisting he would not direct lawyers to break the law. For many observers, the juxtaposition of Reuveni’s contemporaneous disclosures and Bove’s equivocal testimony crystallized the legal questions Boasberg now wants answered under oath.

What exactly did the district court order, and what did the government do?

The underlying litigation is knotty but important. Plaintiffs argued that the Alien Enemies Act — an arcane statute from 1798 designed to allow wartime expulsions — was being stretched to circumvent ordinary immigration and habeas protections. The district court issued an emergency temporary restraining order in mid-March to preserve the ability of detainees to challenge the government’s actions. In the emergency hearing, the court asked whether aircraft scheduled for deportation were still on the tarmac or airborne; government counsel at the time said they did not know. But later data and reporting reflected that two planes carrying dozens of Venezuelans alleged to be gang members did depart and land in El Salvador, where some of those men were transferred into a detention facility. The question for Boasberg is whether those departures happened in conscious disregard of his orders.

The administration’s legal posture has been that the district court’s orders were limited, that the invocation of the Alien Enemies Act presented unique jurisdictional questions, and that later appellate and Supreme Court rulings affected the scope of judicial relief — arguments with which some appellate judges agreed. The department insists it did not willfully violate any valid order. Boasberg, however, has emphasized different facts: he has pointed to contemporaneous statements by administration and allied foreign officials that, in his view, strongly suggest the government believed it had deliberately defied the court’s initial direction. That contrast — between the department’s affirmative policy objective and the court’s account of what it ordered — is at the core of the contempt inquiry.

How the contempt process works, and why a judge’s probable-cause finding matters

Criminal contempt is a blunt instrument: it treats disobedience of court orders as a criminal wrong against the court and the public. Judges rarely reach for it; when they do, they must show a willful and deliberate violation of a lawful order. Boasberg’s initial probable-cause finding was highly unusual because it took the extraordinary step of concluding the government’s conduct was at least plausibly criminal. That triggered an appellate fight over whether a criminal contempt inquiry is appropriate when it implicates national security and foreign-policy prerogatives — areas where courts traditionally show deference. The D.C. Circuit’s more recent decision rejecting the argument that the earlier appellate panel had foreclosed Boasberg’s inquiry effectively returned the matter to the district court for further fact finding. That means Boasberg can now subpoena witnesses, examine documentary evidence, and determine whether the elements of criminal contempt are present.

Why Boasberg may want Reuveni on the stand

Reuveni’s recollection — if the court deems him credible and material — supplies a direct link between high-level policy decisions and what DOJ asked career lawyers to do at the point of litigation. Boasberg has signaled an interest in hearing Reuveni and others directly. If Reuveni testifies consistently with his disclosure, the judge may probe whether senior officials knew their actions risked violating judicial orders and whether they took deliberate steps to circumvent or defy the court. That is the factual question that separates an aggressive legal posture from criminal contempt. The judge’s interest in witness testimony reflects the centrality of contemporaneous knowledge, intent, and communications to any criminal finding.

Who else might be implicated?

The whistleblower’s disclosure names multiple players — including Emil Bove and other senior Justice Department officials — and references meetings where the removals were discussed and legal strategies were marshaled. Prosecutors, agency counsel, and White House lawyers who were involved in those calls and flights could all be asked to testify. The government has other potential defenses: it can argue that its officials believed they were operating within legal bounds; that the district court did not issue a written order commanding a return of flights; or that later appellate and Supreme Court rulings altered the legal landscape such that contempt is inappropriate. Those defenses are serious and might persuade an appellate court, but at the district level the fact-intensive inquiry into who knew what and when will drive the next steps.

What the Justice Department has said — and what it hasn’t

The Justice Department has publicly disputed key aspects of Reuveni’s account, calling some claims false and characterizing the whistleblower as a disgruntled former employee. Officials who were publicly questioned at hearings denied having told subordinate lawyers to ignore court orders. The department’s stance is also tactical: mounting a full-throated public defense while the district court pursues fact-finding risks producing more evidence for the court, but a defensive posture is politically and legally necessary. The recalcitrant posture also helps set up potential appellate issues: if the court issues subpoenas and the department resists, the case could quickly migrate back to the D.C. Circuit and beyond — precisely the path litigants and lawyers on both sides have been preparing for.

Political theatre, legal gravity, or both?

This is not simply theater for media consumers. The case combines high politics (use of an extraordinary executive power, coordination with foreign partners on removals) with foundational legal norms (the duty of every branch to respect the role of co-equal branches and the sanctity of judicial orders). If a court were to conclude that senior government officials willfully defied an order — and that criminal contempt is the appropriate remedy — the consequences could be profound: damage to officials’ careers, potential criminal referrals, and a sharpened constitutional argument over how far courts can police executive action in areas touching foreign affairs. Conversely, if the administration prevails at subsequent layers of review, it will display that judges must exercise caution when their orders intersect with the conduct of foreign policy. Either result would shape the balance of powers debate for years.

Practical next steps in courtroom calendar terms

Practically, Boasberg can issue subpoenas, call witnesses, and schedule evidentiary hearings. The government may respond by asserting privileges, by seeking interlocutory appeals to block testimony, or by arguing that the court lacks jurisdiction because of intervening appellate rulings. Enemies of the contempt probe will likely press for rapid relief from appellate benches and, ultimately, the Supreme Court — given the national security and separation-of-powers arguments available. Advocates for vigorous judicial fact-finding contend that no branch is above the law and that the courts must be able to police willful disobedience even where foreign-policy considerations loom large.

Beyond this case: institutional damage and the morale question at DOJ

The disclosures and the apparent internal friction they illuminate have consequences inside the Justice Department. Longtime career attorneys who expect candor and fidelity to court filings may now view the department’s leadership with suspicion. Reuveni’s firing, and the public dramatics of his disclosure, amplify concerns among rank-and-file lawyers about political pressure, supervision, and the consequences of dissent. Legal practitioners know the long-term value of institutional trust: when that trust frays, the department’s ability to litigate on behalf of the United States effectively is impaired. This inquiry is therefore not just about a handful of flights; it is about whether top officials created a climate where career lawyers felt pushed to substitute political directives for legal judgment.

What to watch for next

Key developments to monitor include whether Boasberg issues subpoenas for Reuveni, Bove, and agency counsel; whether the department resists or complies; whether the D.C. Circuit intervenes again; and whether the Supreme Court is asked to resolve any jurisdictional or separation-of-powers questions that might arise. Observers should also watch the criminal-contempt-related pleadings closely for the degree of documentary support the whistleblower’s account can muster — contemporaneous emails, text messages, or memoranda will make the difference between a credibility contest and a prosecutable case. The political calendar will also matter: the more publicity and traction the matter gains, the more it becomes part of the larger national debate over rule of law and executive power.

A closing thought: why this matters even if the courts never impose criminal penalties

Even if criminal contempt penalties never materialize — because the government persuades an appellate court that its conduct was lawful or because the Supreme Court limits the ability of district courts to coerce the political branches — the inquiry itself performs a crucial constitutional function. It forces transparency about executive action, compels the production of contemporaneous evidence, and subjects high-level decisionmaking to public scrutiny. That scrutiny matters: it is how a constitutional republic keeps a check on the exercise of extraordinary powers. The drama will continue in courtrooms and committee rooms; the outcome will shape how future administrations treat the delicate line between zealous advocacy for executive policy and the duty to obey judicial process.

For now, the reopened contempt inquiry is a reminder that law and politics are entwined, and that in the tug between them, facts — contemporaneous communications, witness testimony, and recorded decisions — will determine whether this episode ends as a footnote, a censure, or a rare criminal finding that redraws the boundaries of permissible executive defiance. The country will be watching as the judge pursues answers that could reach to the highest echelons of power — and as the Justice Department defends its choices in a rare and consequential courtroom drama.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load