When Congress voted this month to force a broad release of government files related to Jeffrey Epstein, it did more than authorize another set of public documents. Lawmakers, joined later by the President’s signature, created a legal mechanism that compels the Justice Department to hand over investigative files, internal communications and records tied to Epstein’s death — the very materials that have been the subject of rumor, speculation and decades of incomplete public accounting. The result is likely to be an avalanche of material that will be parsed by journalists, litigants, and voters — and that could produce answers, contradictions, and new questions in roughly equal measure.

This development is not purely procedural. It lands squarely at the intersection of law, politics, and institutional accountability. For years the public has seen fragments: plea agreements and court filings from Florida in 2008; civil complaints from survivors; a torrent of press reporting. Now, under the new statute, those fragments will sit next to internal Justice Department emails and records about how the Epstein investigation, prosecutions and custodial supervision were handled — and crucially, about what happened in the hours and days surrounding Epstein’s death in federal custody. The question for the country is not only what the documents will show, but what institutions do when exposed to daylight.

The law and the near-unanimous vote that changed the calculus

Congress’s action was unusually bipartisan in both motion and effect. Members on both sides of the aisle pushed the bill through with near unanimity, and it was signed into law — a procedural victory with the unusual optics of a legislative demand for transparency that the White House accepted. The statute directs the Attorney General to compile and release a broad trove of investigative materials by a court-ordered deadline, subject to narrowly defined redactions to protect victims’ privacy and national security. That mandate shifts the burden: instead of a patchwork of requests and court fights initiated by outside parties, the executive branch is now legally obliged to produce an organized, searchable release.

What makes that compelling — and combustible — is that the law covers not only preexisting investigative files such as search warrants and witness interviews, but also internal Justice Department communications: emails, memos and contemporaneous notes that can show how decisions were made and who knew what when. For prosecutors and DOJ staff, internal records are often the most revealing. They reveal the reasoning and chain of command behind prosecutorial choices, and they can either show institutional competence or reveal troubling lapses and tolerances. Congressional drafters and many victims’ advocates argued that the public’s faith in justice depends on transparency into this very internal machinery.

What the documents likely contain — and what they won’t

The scope spelled out in the statute is broad: files related to investigation and prosecution, grand jury materials, internal communications, and records related to Epstein’s custody and death. But “broad” is not the same as “unlimited.” Courts and the Department of Justice will still apply redaction rules to protect victims and ongoing law-enforcement equities. Past fights over similar disclosures — whether involving national-security materials or grand-jury secrecy statutes — confirm that judges will weigh privacy and safety against the public interest.

Still, the universe of potentially releasable material is significant. It includes search warrants and financial records that could illuminate how Epstein financed his operations; witness interviews and contemporaneous investigative interviews that may corroborate or contradict previous accounts; and, perhaps most politically incendiary, internal DOJ emails that could show whether political appointees or other officials took actions that helped or hindered the investigations. Those internal chains of emails are the very records that often differentiate between bureaucratic error and willful interference.

The death files: why the prison record is a focal point

Epstein died while in custody at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York — an event that has been reported as a suicide by the city medical examiner and reviewed in depth by the Justice Department’s Office of Inspector General. The OIG’s investigation documented numerous breakdowns in custody protocols: missteps in monitoring, failures to preserve records and video, and other lapses in detainee supervision that fall short of the standards prisons must meet to keep detained people safe. Those findings were already public in an inspector-general report, but the new law raises the prospect of additional material — internal notes, instant messages, or investigative steps — that could show whether the earlier review was fully comprehensive.

Why does that matter? Because the death is rare — deaths in federal detention are, statistically, uncommon — and because the detainee at issue was an individual at the center of a sprawling international trafficking investigation. Government missteps in custody, whether negligent or systemic, convert a routine failure into a public-interest scandal. The public understandably demands to know whether the OIG got access to everything it needed; whether Criminal Division prosecutors used the full array of investigatory tools; and whether there were forces inside or outside the Bureau of Prisons that impeded a complete accounting. Congress has now ordered those questions to be revisited in the form of material turn-over to the public domain.

Missing footage and technical anomalies: the raw video question

One specific item that has drawn attention is the custody video footage surrounding Epstein’s final hours. Reporting and metadata analysis have suggested that surveillance footage has gaps, edits, or missing segments that complicate the public’s ability to understand the precise sequence of events. Independent reporting has documented that some raw footage shows timestamps and gaps that are inconsistent with the preservation practices the Bureau of Prisons should have followed. Those gaps don’t, on their own, prove criminal manipulation; they do, however, raise reasonable questions about record preservation and the chain of custody for evidence related to a high-profile death. The new legal push means judges and outside reviewers may finally see the raw files and the forensic metadata that explain what was recorded, what was preserved, and what was lost.

For lawyers and forensic analysts, video metadata is the kind of material that settles many questions. It shows whether a file was cut, whether a camera experienced an outage, and whether edits were performed and by whom. If metadata shows missing minutes or nonsequential timestamps, those are forensic red flags that demand explanation. Because of that, one of the central expectations of the new disclosures is that judges, watchdogs and independent reporters will be able to audit not only what footage exists but the integrity of any preserved footage — and why, in some instances, key segments were not preserved.

Political dynamics: why this became a live political issue

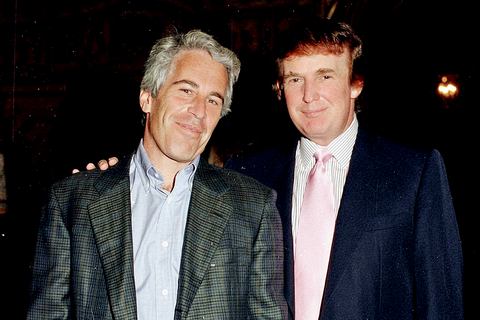

The politics around these disclosures are unavoidable. Epstein’s web of contacts historically touched people across the political spectrum; disclosures that illuminate those connections risk embarrassing powerful actors in both parties. That political reality helps explain why some of the most sensitive materials were previously shielded, and why the bill’s bipartisan support is notable: a rare moment when political actors agreed that transparency outweighed the tactical discomfort of telling hard truths.

At the same time, the law changes the political calculus for the Department of Justice. The executive branch must now reconcile its duty to enforce the law with the new statutory demand for release. For attorneys and civil-liberties observers, this is an institutional stress test: will the Department fully comply, aggressively litigate narrow exceptions, or seek to delay release through protracted redaction fights? The answer will shape how the public perceives institutional accountability in highly politicized investigations.

What transparency may reveal — and what it probably won’t

There are three realistic outcomes as the documents roll out.

One: the records fill in procedural blanks and confirm the broad outlines already known — that there were investigative leads, prosecutorial judgments, and lapses in custodial supervision that, while serious, do not point to an organized external plot. That would still be meaningful: confirmations of missteps would validate survivors’ concerns while exposing operational failures that merit institutional reform.

Two: the records provide new, previously unknown connections or evidence that require fresh criminal or civil steps. That material could lead to new inquiries — subpoenas, grand-jury probes, or civil litigation — depending on whether prosecutors or other law-enforcement entities find actionable information.

Three: the release generates more noise and contradiction than clarity. Records often present messy, inconsistent accounts. Emails don’t come with context; draft memos don’t show final reasoning. A partial or raw release can produce headlines without producing definitive answers, and that fragmentation can exacerbate public mistrust rather than resolve it.

The honest lesson is that transparency is necessary but not sufficient. Releasing files without careful forensic work and responsible reporting risks inflaming conspiracy rather than clarifying truth. Yet hiding documents or delaying release risks deepening suspicion. The law chooses disclosure as the primary corrective mechanism. How that plays out will depend on judges, redaction practices and the quality of independent scrutiny.

What investigators should be watching for first

Practically speaking, watchdogs and journalists will look first for several categories of records:

• Internal DOJ and Bureau of Prisons communications that show who knew what, and when. These can reveal whether departmental lines were crossed or preserved.

• Forensic forensic evidence — metadata from videos, chain-of-custody logs, and communications about evidence preservation. These will address whether critical files were preserved intact.

• Interview notes, witness statements and search warrants that outline investigatory leads and how the prosecution assessed them. Those materials can change the narrative around prosecutorial choices.

• Grand-jury materials that courts may deem appropriate to release in redacted form. Even limited grand-jury testimony can illuminate investigative windows previously obscured by secrecy.

Careful analysis of these materials will separate procedural incompetence from intentional obstruction, or conversely, will show that sloppy systems created the conditions in which a tragedy and a scandal could coexist.

The legal fights ahead

Expect litigation. The Justice Department has already moved in court to reconcile the statute with existing court orders and privacy rules, and victims’ counsel, defense lawyers, and institutional litigants will press their own claims. Some judges may order fast, highly redacted disclosures; others may demand more surgical releases with extensive privacy protections. The timeline set by the statute is ambitious, and the practical challenges of preparing thousands of pages of material for public consumption — while protecting legitimate privacy interests — are nontrivial.

Those procedural fights matter. They will determine whether the public gets a usable trove of documents or an opaque release that requires months of FOIA litigation and piecemeal unsealing. They will also determine whether this moment produces durable institutional reforms or merely a transient news cycle.

A caution about conclusions

Finally, responsibility demands a caveat. Documents are powerful, but they are not self-interpreting. Emails can be sarcastic, notes can be incomplete, and metadata can be misunderstood without proper forensic expertise. History shows that document dumps can fuel misinterpretation as often as they resolve mysteries. That is why the work ahead requires careful, methodical review by attorneys, forensic analysts and reputable journalists who can place material in context.

Congress’s decision to force disclosure is, by design, a corrective against secrecy. If executed responsibly, the result can be a clearer public account, institutional reforms, and renewed confidence that high-profile matters will be subject to scrutiny. If executed sloppily, it could simply deepen confusion. The documents themselves will not close the chapter — they will open one. How that chapter reads will depend on the diligence of the people who parse it.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load