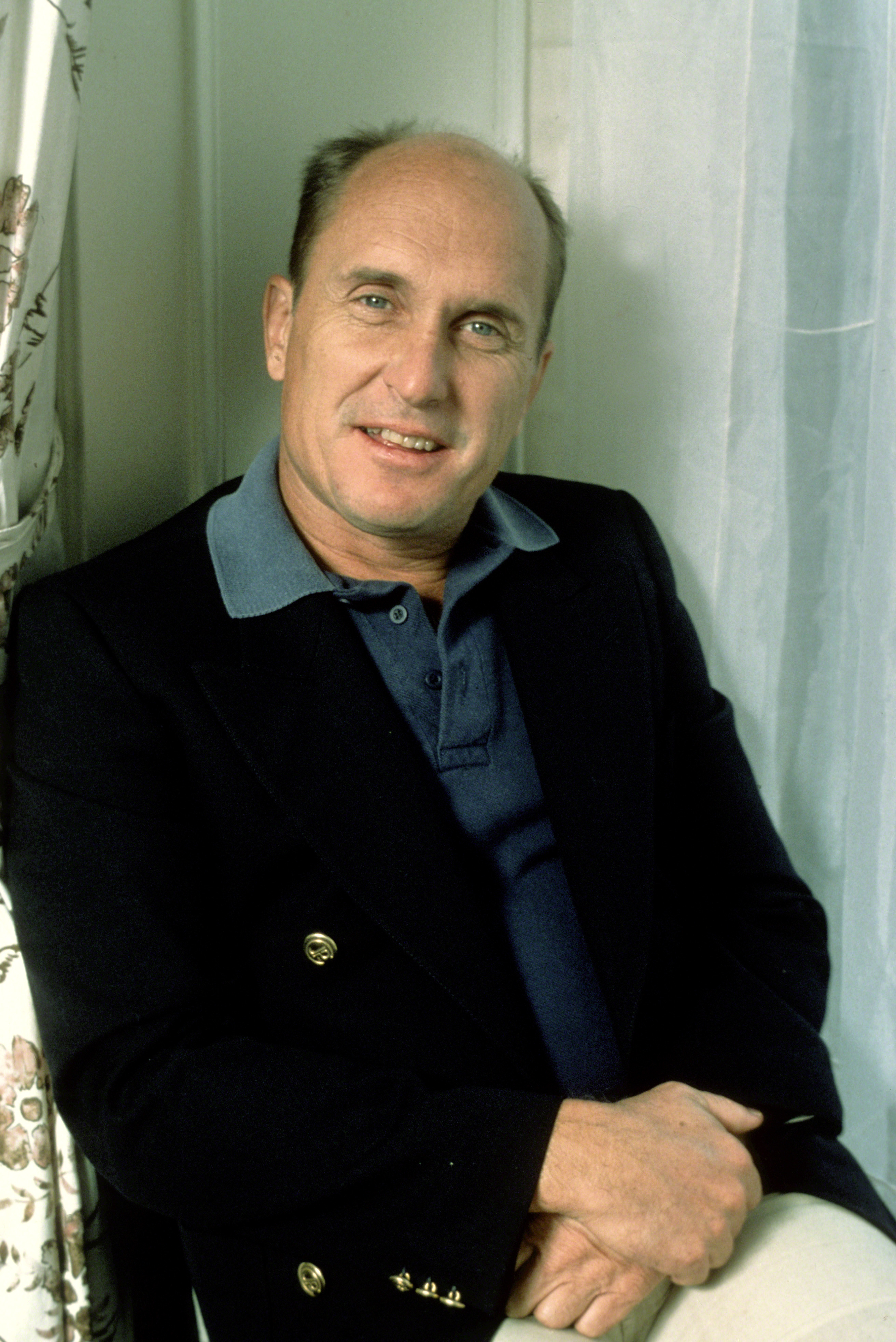

Here’s the part about Robert Duvall—at 94—that lands with a weight the industry press rarely knows how to carry: the man was forged in quiet, not spectacle. He became the steel backbone of American cinema not by shouting for attention or drowning scenes with fireworks, but by outlasting every storm that tried to push him off the set, off the stage, out of the life he chose. He moved through the business like a weather system you only notice when the sky clears: steady, disciplined, deeply human. The tragedy, if we’re willing to use that word for someone who has lived so fully, isn’t just about losses or marriages that didn’t hold. It’s about how a life this hard-won teaches you what stays—and what inevitably slips away.

Let’s trace it honestly. Not with a museum plaque, not with a press release, but with the patient clarity of a reporter who’s been in too many greenrooms and stood through too many “we’ll call you”s to be fooled by safe language.

He didn’t come out of the cradle destined for soft landings. San Diego, 1931. A home shaped by discipline and lineage—his mother with ties to Robert E. Lee, his father a future rear admiral. Picture the rooms: polished wood, straight-backed chairs, a love expressed in duty rather than warmth. The family moved as the Navy does: Annapolis, coastal bases, temporary walls. He learned not to unpack fully. That matters. It makes you an observer. It teaches you how to notice small things like breath patterns and sore silences—things actors spend careers trying to fake.

He said later that he was terrible at everything but acting. That line lands differently when you understand it as an admission, not a bit. Some people find their calling at a podium; others find it in the long shadow of a father’s expectations. He didn’t put on the uniform his father imagined. He put on other lives. That choice didn’t heal the rift, but it gave him a language to translate pain into purpose.

Army service in the early ’50s wasn’t a myth-making chapter for him; it was routine, low-drama labor punctuated by a minor production and a quiet spark. New York followed—1955, cold rooms, thin meals, rent-shocked addresses that looked better on the lease than they felt in winter. Neighborhood Playhouse under Meisner. The names around him would become famous—Hoffman, Hackman, Caan—but back then, they were just underfed actors holding hot paper cups like lifelines. He rationed apples, wore through shoes, took the jobs you take when ambition outruns money: Macy’s, mail carts, early mornings that teach you how discipline tastes when you can’t afford breakfast.

What he built onstage in those years wasn’t reputation. It was stamina. Plays at Gateway and off-Broadway, more show titles than paychecks. Rejections that didn’t lace themselves with cruelty, just indifference—the quieter kind that sends you home wondering if the city even knows you’re alive. And then the crack in the wall: Eddie Carbone in A View from the Bridge under Ulu Grosbard. Arthur Miller watching not with courtesy, but with the narrowed eyes of a man hearing a new frequency. An Obie arrived, but awards are misleading. What he won wasn’t hardware. It was a lease on legitimacy. Proof that the hunger could be for something.

Hollywood noticed in increments. To Kill a Mockingbird—Boo Radley, no lines, all presence. Silence that plays. The ’60s didn’t hand him a fast track; they made room around the edges and invited him to stand in the threshold. He learned how to make stillness the loudest thing in a room.

Then came 1972. The Godfather, Tom Hagen, Francis Ford Coppola aiming for the rafters. Duvall didn’t bully the frame; he stabilized it. Beside Brando, Pacino, and Caan, he held the moral geometry—the fixer with a conscience, the calm that signals danger more clearly than yelling ever does. Everybody had to be excellent every second, he said. He was. Not with weaponized intensity, but with that kind of authority you can’t rehearse if you don’t have it in you.

The next hammer came in 1979, Apocalypse Now. The chaos has been mythologized so often it’s hard to distinguish fact from folklore. Here’s what holds: blistering heat, tropical storms that re-wrote call sheets, helicopters recalled mid‑scene, a production on the brink. Duvall’s “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” became a pop-culture fossil, but the performance wasn’t built for quotes. It’s the posture that sticks—the soldier who knows the madness and doesn’t blink. It reads like survival because it was.

Tender Mercies opened an entirely different door. Plenty of actors can play hard; few can play fragile without sentimentality. At 52, he sang the songs himself, carried the humility of a wrecked man without turning him into a parable, and walked that thin line between vulnerability and steel like he’d been living there for years. The Oscar didn’t crown him; it caught up to him.

There were other peaks, of course. Lonesome Dove—Gus McCrae, the kind of role that makes writers feel lucky to be handing lines to an actor like that. The Apostle, a decade and a half later: written, directed, financed by Duvall. He didn’t negotiate the industry’s permission; he built his own runway and took off. The movie landed—not as a financial miracle, but as proof that integrity can be a business plan. After that, even as age set in, he kept working like a man who can no longer afford to pretend. A Civil Action, The Judge—choices that required reading until your eyes burn and then showing up under the lights with all your blood still in the scene.

The industry didn’t always know how to value that kind of steadiness. When The Godfather Part III rolled around, the money conversation got ugly. Duvall didn’t posture; he spelled it out: he could live with Pacino making twice as much—just not three or four times. That line tells you everything about dignity in a business that treats it like a luxury. He walked away. The movie lost Tom Hagen. He kept his compass. Plenty of men are brave when a fight will be televised. Being brave within contract language? That’s rarer.

The private world was not kinder. Three marriages that taught him different lessons about love’s endurance and its limits. Barbara Benjamin, a dancer with two little girls who brought a softness into his life he hadn’t known he missed until it was there—crayons on tables, shoes by doors, the symphony of a house alive with small voices. That’s the part the public rarely sees in men like him: the tenderness, not yet father, but something close enough to rewire hope. The dream of a child together unraveled quietly, medically, brutally. When men crack jokes about shooting blanks, it’s almost always a bandage for a wound they can’t describe without bleeding. The marriage ended in dignity, and the hardest truth wasn’t the legal part. It was the goodbye to the little hands that had wrapped around his fingers. Those girls still called him Bobby later, sent notes, kept the bond alive. People who frame his life as solitary forget this: love doesn’t evaporate just because a marriage does.

Gail Youngs came with fire and motion and the kind of creative electricity that makes you believe a second act can be a first act if you hold on tight enough. They argued and dazzled and lived intensely. Sometimes intensity bonds; sometimes it scalds. In time, it scalded. He left that marriage with another tender bruise—the realization that two people can love deeply and still not fit the daily shape of each other’s lives.

Sharon Brophy followed—a dancer with discipline, a marriage small and sincere. They didn’t fight. They drifted. Quiet can be gentler than storms and just as lethal to a bond. By 1995, they ended without spectacle or blood. Again, the public missed the nuance: not every collapse is dramatic. Sometimes it’s two people who can’t sync their rhythms no matter how carefully they count.

And then Luciana Pedraza, the chapter that matters most now. Buenos Aires bakery, a 41-year age gap, the kind of fact that tabloid culture lives to flatten into controversy. Only, it wasn’t a scandal. It was a slow-building devotion that bridged years and continents. They married in 2005 after nearly a decade of learning how to be in each other’s presence without pretending it was effortless. Over time, the marriage bent—age does that to love—it didn’t break. She learned the language of his later years: slower walks, pill schedules, careful steps, memory pauses. He learned the humility of letting himself be cared for without turning care into apology. They restored homes in northern Argentina. They built tenderness where neither of them could build children. It held.

The losses that arrived were sharp. His younger brother, John, the law-side anchor who understood the boy before fame redesigned him, died in 2000. People underestimate what it means to lose someone who knows your origin story. It doesn’t just remove a person; it removes context. A compass goes quiet. He softened around that grief—spoke less, sat longer, watched the porch light change and said things like “I wish John had met you longer,” a sentence gentle enough to carry a lifetime of ache.

James Caan’s death in 2022 cut differently. It’s almost silly to say “Sunny” when what Duvall lost was a brother of a half-century, a witness to the trenches. Their chemistry in The Godfather wasn’t manufactured; it was the glue of long days and laugh-heavy nights and a tolerance for each other’s edges. Duvall called the loss “tremendous.” The word is modest. The grief wasn’t. He watched old scenes, not for the craft, but to feel the presence of a friend whose laughter lived between takes, in the margins, off-camera. Losing Caan wasn’t losing a colleague. It was losing a mirror to your younger self.

Money is the easy part of any late-life portrait. Yes, he built a fortune—call it $70–75 million on paper if you need a number—across farms, films, residuals, and artifacts that capture a career in objects: scripts, photographs, notes. He kept a Virginia farm like a figure out of American mythology: porches that breathe; a library with annotated pages; horses as both work and company; a recording barn turned rehearsal sanctuary. In Buenos Aires, high ceilings, a corner worn by tango, sunlight on frames where the man looks less like an icon and more like a husband who learned how to sit still beside someone who chose him daily.

He planned with intention. The will divides assets in ways that honor both love and memory: the estate and rights toward Luciana, the Buenos Aires home shared with their foundation, and a private allocation for the two daughters from his first marriage—women he still calls, still hears from, still loves in the quiet legal language of affection that outlasts categories. If you’re hunting for the moral of that clause, here it is: fatherhood isn’t only in blood; it lives in years and dinners and stories read when you’re too tired to do it well and do it anyway.

The late days are gentle. Mornings on the porch with coffee warming his hands, sunlight across fields, scripts read aloud for the pleasure of cadence rather than the duty of preparation. Afternoons balancing small tasks with long memories. Photographs sent from women who grew up and had children of their own and still call him Bobby. Evenings beside Luciana, saying the hard things softly: the marriages that broke, the child who never came, the girls who did, the friends who left, the brother who stood beside him in rooms where silence did the talking. Fame no longer defines him. Wisdom does.

So what, at 94, is the tragedy? Not the clean, headline-ready kind. The quiet kind. The heartbreak of knowing you did the work right—built craft from restraint rather than noise, built love from choice rather than impulse—and still learned that life takes, even from those who give. The dignity of walking away from a film that undervalued you, knowing the public would miss your character and not your calculus. The ache of three marriages that taught you the contours of love’s limits before you found one that could hold. The soft knife of losing the last witnesses to your origin. The way the body eventually enforces a pace the mind resists. The way memory becomes both refuge and reminder.

But if we stay on tragedy, we miss the other thing: a life that became larger than awards. Duvall’s gift wasn’t just performance. It was discretion. Honesty where embellishment would have paid better. Discipline where fury would have made better copy. The strength to carry slights inwardly and turn them into work rather than noise. Plenty of actors are great at pretending depth. Robert Duvall spent seventy years proving that depth can be lived so thoroughly it barely needs to be performed.

Here’s the professional truth I carry after decades of watching careers rise and contract like tides: greatness is rarely granted. It’s earned in the hours when no one is watching—when auditions end with closed doors, when winter air becomes a second enemy, when you pour yourself into roles that don’t yet pay for the rent they cost you. Duvall didn’t chase myth. He chased rightness. He didn’t rise quickly. He rose correctly. That’s a sentence I’d like to see printed more often.

His legacy won’t be measured by wealth or even by titles. It’ll be measured by a style of acting that trusted silence; by a kind of masculinity that learned to hold tenderness without apology; by a version of success that doesn’t rely on volume. He taught audiences to listen. He taught directors that steadiness can carry more charge than storming. He taught younger actors—if they were paying attention—that the hot shine of early recognition is worth less than the cool flame of staying power.

What remains now is a man who sits in the soft light beside someone who stayed. A pair of daughters who remember a house filled with crayons and stories and still send photos across years. A farm that holds not trophies but breath. And a body of work that hums at a frequency we associate with the best of American cinema: modest, muscular, moral.

If the sadness of his late life feels “beyond heartbreaking,” it’s because breaking hearts was never his sport. He mended them. He showed us men who fail without collapsing, men who grieve without punishing, men who keep working when comfort would be easier. That’s not Hollywood’s favorite storyline. It’s better. It’s real.

At 94, the lesson is quiet and clear. You are not remembered for what you gain. You’re remembered for what you continue to give when the storms have burned off and the porch is your theater. Robert Duvall gave the American screen its backbone. Off-screen, he gave the rest of us a map: how to live with discipline and tenderness at the same time; how to admit losses without letting them harden you; how to be great and still be good.

There are softer ways to end this, but softness would miss the point. He earned everything the hard way. He held it gently. That’s the rare combination. That’s the feature worth writing.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load