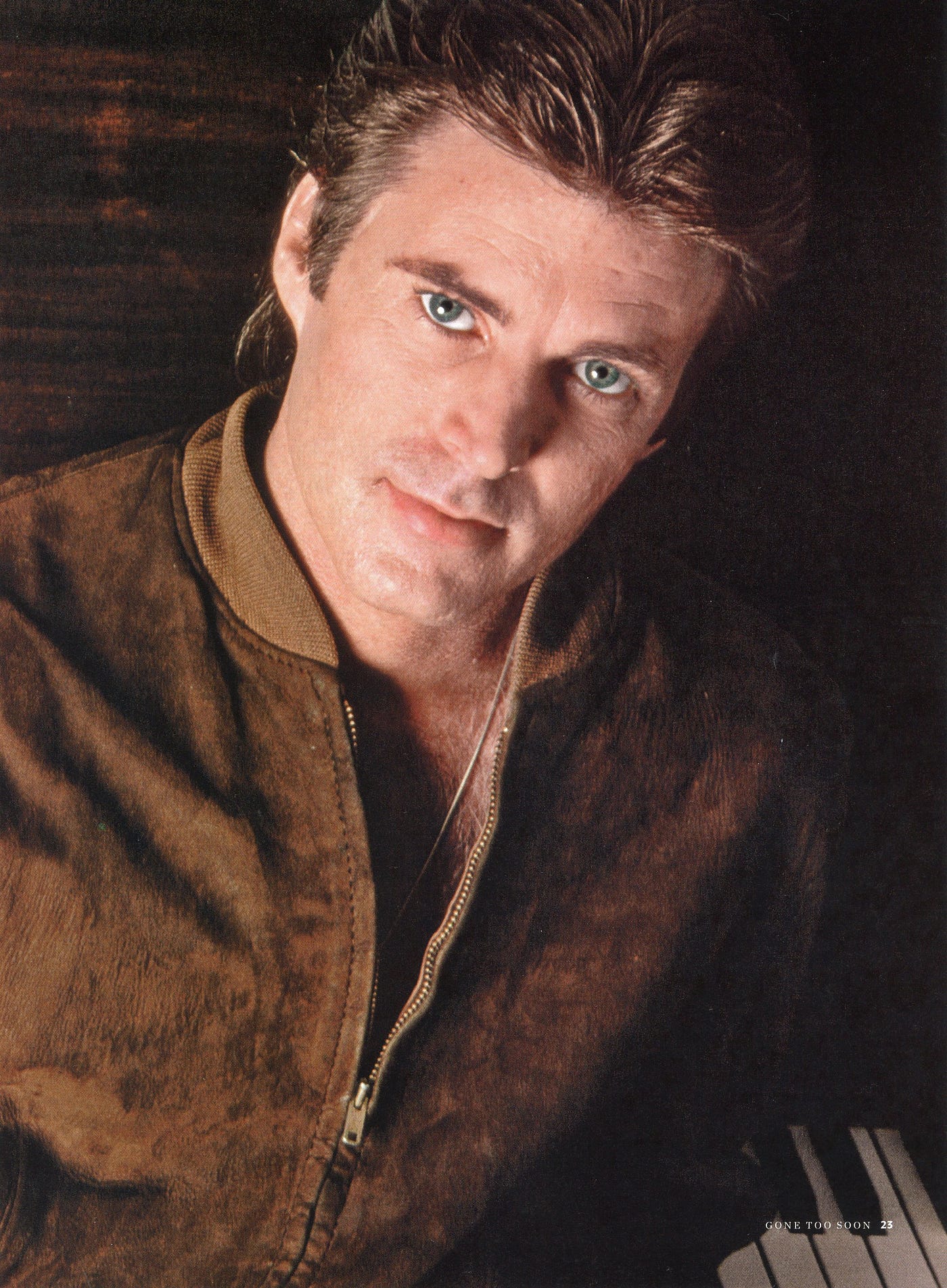

The Boy Who Belonged to Everyone: Ricky Nelson, Inheritance, Reinvention, and the Bill That Came Due

You don’t choose to be born into a show. By the time Ricky Nelson figured out he wanted a life of his own, the country already felt like it owned him—his schedule, his smile, his soft, steady voice that somehow sounded more honest than the era allowed. If you want the simple version, it goes like this: cute kid on the family sitcom becomes teen idol, gets flattened by Beatlemania, tries country-rock, writes one perfect manifesto (“Garden Party”), dies too young, and leaves behind a split verdict—was he a pioneer, or a casualty of fame’s whimsical math? But the clean story shortchanges the real one, which is messier and, in the way the best American stories are, more interesting: a sickly kid with asthma carrying scripts across a bedspread; a teenager counting nickels while his likeness sells magazines; a man who keeps relearning that the public loves you right up until you ask it to love the person you grew into.

Ricky didn’t walk into show business. He was ushered in like a ring bearer. Imagine being born in 1940 to parents already fluent in the grammar of microphones and ad copy. While other children learned bedtime stories, Ricky learned marks taped on studio floors. Breath control before bike riding. Camera angles before algebra. The family house functioned like a set. The set functioned like a living room. It’s not trauma in the operatic sense; it’s subtler—the erosion that comes from being curated before you’ve decided who you are.

And then there’s the money. It’s always the money. America has a way of valuing youth while making sure the youth don’t see the ledger. Ricky’s earnings—serious money, not allowance levels—were centralized, “managed,” rationalized as investment in the brand. It’s the boring cruelty of commerce: the checks clear, the kid learns to fish soda bottles out of machines to take a girl to the movies. Let that image sit. It’s not Dickensian. It’s worse—because it happens in plain sight with smiles all around.

If his childhood reads like a contract written by other people, adolescence arrived like a clause in fine print. The television audience who adored him also told him who he was allowed to be. School didn’t soften it. “TV boy,” they teased, as if he’d been photocopied from a Thursday-night schedule and delivered accidentally to homeroom. He tried the small rebellions kids reach for when they can’t articulate their needs: cutting class, pranks, tanking English just to test whether anyone saw Ricky the person, not Ricky the product. It’s the private logic of a public life. If no one lets you choose anything, even bad choices feel like oxygen.

Then came the first spark he chose for himself: music he wanted to play, not music that fit a family brand. Elvis flickered on a TV and something cracked open. Not envy. Recognition. More importantly, permission—self-granted. He made a case to his father to sing, and for once the why came from inside. March 26, 1957: a studio that smelled like warm tubes and old wood, two songs (“I’m Walkin’,” “A Teenager’s Romance”), a kid pressing his pulse onto tape. Televised performances turned exposure into ignition. Records flew. “Poor Little Fool” became the first number one on the Hot 100—one of those officially-sanctioned trivia facts that papers over the unglamorous truth: no chart position cures the ache of living on cue.

His rise wasn’t about volume or spectacle. Teen idols often thrive on the big gesture, the wet sheen of sweat, the mic stand as lance. Ricky’s octave was restraint. He didn’t try to seduce you so much as confide in you. The voice was soft and even. It made the loudness of the era feel like a costume. With “Lonesome Town,” the mask slips a little more. It’s a small song, spare to the point of brave, and teenagers wrote to say they felt less alone because he sounded lonely, too. You don’t out-scream the crowd; you out-honest it.

But the machine exacts a price regardless of tone. Tours turned feral. Girls pounded on car windows; police became stagehands who moved the singer for his own safety. It read as hysteria in headlines and hunger in person. Even then, the body keeps its own books. Exhaustion set in. He collapsed in Hawaii in ’62 while the people around him argued over what the schedule could bear. Doctors warned. Fathers overruled. The show didn’t stop because the show rarely stops; it simply adds a new clause: fatigue is part of the job.

And then the seismic shift: the British invasion. The industry recalibrated in a season. American teen idols were refiled as yesterday’s sensation. Shelves that once bowed under stacks of Ricky Nelson records tilted toward a different promise. Here’s the part the glossy biographies rush: he didn’t vanish; he adapted. Quietly. Patiently. He assembled the Stone Canyon Band and walked into country rock a half step before the press had a name for it. If you listen forward, you can hear the fingerprints on sounds that would later mint fortunes—the California harmonies, the clean lines, the melancholy ease. He moved from poster to architecture without demanding a parade.

Of course, progress has a way of drawing blood. Madison Square Garden, 1971. He walks out wearing velvet and bell bottoms, hair longer, sound modernized, heart plainly on the line—and the crowd turns. They wanted the version that made them feel safe, the boy on the family show, the pop innocence curated for them. Reinvention requires a grace the public seldom extends. He finished another song and left with a wound every working artist recognizes: the distance between who you were and who you are will be measured out loud by strangers.

That kind of bruise either hardens you into bitterness or forces the work to tell the truth. “Garden Party” is the latter—a tidy manifesto set to a gentle sway. You can’t please everyone, so stop trying. It’s anti-bombast. If Mick had written it, people would call it swagger. Because Ricky wrote it, they called it resignation. Listen closer; it’s freedom wearing good manners. He’d made a career complying; the best of his later music negotiated on his behalf.

The industry, however, isn’t sentimental. Labels fold, A&R men pivot to the next thing with quicker return, and great songs sometimes disappear into paperwork before they reach air. The spotlight loosened. That’s the nice way to put it. The less nice way: the apparatus that prints stars also prints obsolescence. You can spend your twenties being escorted through crowds and your thirties trying to convince a receptionist to buzz you up. It isn’t a fall so much as a fade, and fades are cruel because they give you time to feel every inch.

Meanwhile, life kept presenting bills. The marriage—hopeful at the start—collapsed under touring, habits, anger, the ordinary humiliations of two people trying to be themselves while a calendar eats the week. Divorce, custody fights, the strange aftertaste of lawyers in the family kitchen. The transcript’s account names a son, Eric, barely acknowledged beyond legal minimums. That’s a straight wound; there’s no generous way to frame it. Legacy may be written by love, but it’s notarized by behavior. You don’t get to sing your way out of certain responsibilities.

Then comes the woman who wasn’t a wife and became a home. Helen arrives in 1980 in the narrative—a steady hand, a quiet room in a noisy house. Without mythologizing, every life needs someone like that: a person willing to accept the gap between what the world sees and who you are when the lights die. They traveled together. They made a life that functioned precisely because it wasn’t designed for public consumption. And then the small, preventable cruelty aviation sometimes hands out—a heater malfunction, fire in the air, and no time to bargain with gravity. December 31, 1985. Ricky, Helen, and others gone in a sky that didn’t care about discographies.

Grief didn’t quit at the crash site. Families rarely agree on definitions of legitimacy after a death, and power tends to flow through blood and precedent, not feeling. Helen was refused a place beside him. She was barely acknowledged at the funeral. The omission doesn’t rewrite the love, but it does make a statement about who gets to curate a life after the protagonist exits. Estates were argued over. Old contracts coughed up lost royalties—millions, allegedly—which is the dullest Greek chorus in American entertainment: the discovery that the money would have mattered most before it turned up. It wouldn’t have changed the music. It would have changed the weather around the man who made it.

Pause on a different part of the record: the acting. He didn’t just serenade America; he tried to test himself in rooms eager to condescend. “Here Come the Nelsons” made him a household object. “General Electric Theater” in ’58 let him be vulnerable in a way ABC airwaves didn’t prioritize. “Rio Bravo” in ’59 put a boyish kid next to John Wayne and Dean Martin, and he didn’t blink. He won a Golden Globe nomination for his trouble. Hollywood patted his head, then went back to debating whether a former teen idol could be permitted gravitas. The industry’s memory of young men who fired up teenage girls is, to put it generously, selective. It prefers them to remain safely framed.

What stays, if you strip the story back to wood, is the sense that Ricky kept trying to do something very American and very hard: square a public inheritance with a private appetite for self-determination. He wanted to choose his friends, his sound, his hair, his tempo, his off-duty life. He wanted a bicycle. It sounds trivial until you realize it’s not about transportation. It’s about agency—the right to decide how you move through the world. When teenagers wrote to say “Lonesome Town” made them feel seen, it wasn’t because he was the handsomest, or loudest, or flashiest. It was because the guy on the other side of the record sounded like someone also waiting to be allowed to be himself.

It’s fashionable now to treat teen idols as disposable—foam on a wave. But go back and listen without the costume jewelry of nostalgia. The early hits are cleaner than the era requires. The later country-rock sides carry a kind of poised humility pop rarely rewards. The live cuts, when the rooms were kind, have air in them—players listening to each other instead of wrestling for space. And “Garden Party,” smugly quoted and rarely absorbed, is a small master class in drawing a boundary without starting a fight. He doesn’t declare independence; he practices it.

There’s a temptation to tidy the ending. Don’t. The plane crash doesn’t provide narrative symmetry. It prevents it. He didn’t get to enjoy a legacy lap or the revival cycle that comes for men of his era who live long enough to be reissued. We fill the absence with projections. Some paint him as martyr, some as cautionary tale, some as pioneer whose influence runs through the California sound whether or not everyone wants to write his name in the credits. The truth likely holds all three: he was used, he learned to use back, and he built things that lasted past the fading of his own spotlight.

And yes, if you’re keeping a quiet scorecard, there are marks against him that don’t buff out—parenting that never showed up the way it should, professional choices that put career above care, a habit of letting other people manage his life until they managed him into corners. The idol made mistakes. The adult did, too. That’s not a footnote; it’s part of the portrait.

What I keep returning to is the image at the beginning: a wheezing boy, scripts on a blanket, a house designed for broadcast. The miracle isn’t that he became famous. The miracle is that he still managed, in the middle of all that management, to carve out a voice that felt uncoached. When he got the chance, he chose songs that fit his actual shape. When the crowd booed the new shape, he wrote it into a melody and kept going. When fashion moved the goalposts, he picked up a steel guitar, rewired his band, and worked in a lane nobody had paved for him yet.

A lot of men from that era never figured out how to grow older in public without embarrassing themselves or hating the audience for watching. Ricky’s later work isn’t perfect, but it isn’t desperate. It sounds like a person who has made peace with the size of his silhouette. That, in the unofficial handbook of show business, counts as grace.

The shocking “new details” that set corners of Hollywood buzzing every few years are less about revelations than about attention spans. We rediscover the same essentials and package them as news: the controlled childhood, the financial exploitation, the reinvention, the Garden Party moment, the stubborn decency of the voice, the plane, the hard aftermath. If you’ve been around the block with stories like this, you learn not to chase the exclamation point. The comma is more honest. He suffered, comma he adapted, comma he helped shape a sound, comma he wasn’t done making his case when time ran out.

So what do we do with him now? Maybe nothing performative. Maybe we acknowledge that his life demonstrates a simple equation: when a culture borrows a child’s identity to entertain itself, the debt compounds. The person spends adulthood negotiating the interest. Ricky did it with unusual gentleness and a few key flashes of steel. He wasn’t the future by the early sixties. He was the bridge—between scripted wholesomeness and self-authored adulthood, between teen pop and a country-rock current that would eventually feel inevitable.

If you’re inclined to update the canon, you can place him where he belongs: adjacent to the greats, essential to the lineage even if he isn’t the headline. Put on “Lonesome Town” when the house is quiet and you’ve made the mistake of looking at old photos of yourself. Put on “Garden Party” when you’re about to say yes to an invitation that insults the person you’ve become. Put on the Stone Canyon Band sides when you want to hear someone swap vanity for tone and live to tell about it.

He began as a boy furnished to the public, then spent the rest of his time furnishing a self. He didn’t get all the way there. Who does? But in the end, he left enough of himself on tape to make the case: the point of surviving a script isn’t to burn it. It’s to learn to write in the margins until the margins become the page. That’s Ricky Nelson’s legacy, shocking only to people who haven’t been listening closely.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load