The loudest ones usually come with a missing footnote. A video title screams that Paul Newman dropped a bomb on national TV in 1986 about Golden Age actresses “secretly born male,” and for five minutes the internet forgets to breathe. Then you go looking for the tape, the transcript, the contemporaneous coverage—and the trail goes soft. Not disputed. Absent. What we’re left with is a mash of recycled rumor, shadowy “files,” and the classic promise that “No. 4 will shock you,” which is a sure tell the story is optimized more for watch time than for truth.

But let’s not punt the conversation. Gender, performance, and power have always braided through Hollywood like a live wire. The studios minted rigid templates—what a man looks like, what a woman looks like, how each should move, talk, kiss—and then hired artists who ignored, subverted, or simply refused those instructions. If we’re going to talk about the Golden Age and its gender ghosts, let’s do it with a clear head, a reporter’s spine, and some compassion. No breathless exposés. No medical voyeurism. Just the people, the work, and what survived the machinery.

Below is a structured walk through the players the rumor mill loves to claim, plus the two who actually lived their truths in public. Take it as a long conversation at a kitchen table, not a sermon. I’ve been around the archives long enough to know how myth grows. It’s generous with color and stingy with receipts.

Candy Darling: a name that deserves a clean sentence

Start here, because we can. Candy Darling’s life is documented—on film, in photographs, in letters, in the recollections of friends and collaborators. She grew up on Long Island, came to Manhattan the way many queer kids do: raw-nerved, broke, stubbornly determined. The Warhol orbit didn’t make her; it amplified her. Women in Revolt and Flesh put Candy on screen in that cool, merciless way Warhol had—long takes, minimal protection. The city was fascinated. The industry was less impressed. Directors wanted the aesthetic without the responsibility. They’d cast a trans woman as an idea but not as a person.

People who knew Candy talk about the look in her eyes, which is a kind of reporting in itself. In photographs, that gaze reads like self-possession edged with a dare. On stage, in bars, in tiny parts that should have led to larger ones, Candy pushed against the ceiling. The violence she endured and the precarity she lived with are the ugly facts the legend tries to sand down. There’s no neat ending. She died at 29. The city kept spinning. But if you pay attention to the line of influence—from Warhol to Reed to the drag and trans performance scenes that followed—you see Candy’s silhouette under a lot of lighting rigs.

Christine Jorgensen: media spectacle, human clarity

Christine Jorgensen didn’t ask to be a hinge of history, but when the hinge creaked, she didn’t flinch. The New York Daily News headline—EX-GI BECOMES BLONDE BEAUTY—turned Christine into a screen on which mid-century America projected its fear and fascination. She gave interviews, she lectured, she performed. Not to be consumed, though that happened; to be understood. “I am not a mistake,” she said, in effect, and then continued living a life that proved it.

The lore likes to drag in intelligence files and clandestine memos, because those give the story a spy-movie gloss. What actually matters is simpler: Christine’s insistence on personhood at a time when the culture wanted either a curiosity or a cautionary tale. She forced a conversation out of euphemism. She made editors choose language. She made lawmakers stare down their own paperwork. That doesn’t fit neatly in a scandal reel, but it’s the part that moved the world.

Marlene Dietrich: tuxedo as thesis

Every decade or so, someone “discovers” Marlene Dietrich all over again. It usually starts with Morocco and the tuxedo and the kiss. Then the rabbit hole splits: one branch is serious film study—how Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg engineered a glamor that could feel both decadent and disciplined; how a costume can be a weapon. The other branch drops into anonymous files, confiscated notes, and a breathless suggestion that the mystery must be anatomical. It’s not. The mystery is performative power.

Put the Morocco scene on mute and watch her posture, the weight she puts into the heel, the precise hold on the cigarette. This is a woman teaching the camera what to desire. She didn’t “become a man” by putting on a tux; she made masculinity blink first. Did she destabilize gender in the most public forum of her time? Absolutely. Did she “reveal” a hidden sex? No credible archive supports that claim, and I’ve looked.

Greta Garbo: enforced silence, deliberate privacy

Garbo’s quiet wasn’t a coy stunt. It was a negotiation. She learned, probably before most of her peers, that privacy is the only currency a star can control when contracts, press agents, and censors can auction off everything else. The press called her “the Swedish Sphinx,” which is a tidy way to admit the industry never cracked her open. Rumors filled the vacuum: blocked passports, conflicting documents, whispered scars. They make for terrific dinner-party anecdotes and miserable history.

What we can say with a straight back is this: Garbo’s image—angular, unsmiling, resistant to forced softness—refused the conventional choreography of femininity. The camera adored her and could not domesticate her. That friction birthed a thousand “what is she” columns. The work is still the better answer. Watch Queen Christina. The final close-up at the prow of the ship isn’t a woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a queen. It’s Garbo playing a sovereign whose interiority outpaces the language around her. Gender becomes the wrong question because the performance has already moved on.

Joan Crawford: labor, control, and the price of the mask

Crawford is where people’s appetite for revelation tends to curdle into cruelty. The rumors are gaudy: Vatican files, vanished police records, clandestine hormone clinics. What’s on the record is less lurid and more demanding. Joan Crawford built herself, one decision at a time, in a system that punished women for every ounce of autonomy. She protected her image with a ferocity some read as vanity and I read as professional survival. Imagine living with a studio retoucher in your head, 24/7, and then imagine people calling you “cold” when you refuse to undress in a communal dressing room.

If you want to understand Crawford, don’t chase the mirror lore. Watch Mildred Pierce with the sound off. Track the angles of the chin, the spine that won’t bend, the determination verging on anger. That isn’t a man in a mask or a secret in search of a headline. It’s a worker who understands the only safe place is the exact center of the frame, and even then only for the length of the take.

Katharine Hepburn: trousers as policy

Hepburn wore pants because they were practical and because she could. The studios didn’t know what to do with that. Culture rarely does. So the whispers start: coded file designations, amended certificates, a colleague’s speculation retconned into evidence. I understand the impulse—it’s a way to make sense of someone who simply refused to perform the role prescribed to her. But it’s a small way to understand a large career.

Hepburn’s legacy is not an unsolved riddle. It’s a template: speak directly, choose work that respects your intelligence, decline the condescension of charm when it’s used to corral you. She played women who made choices, often difficult ones, without apologizing for wanting the life they wanted. In a culture that still treats female ambition like a plot twist, that’s the point.

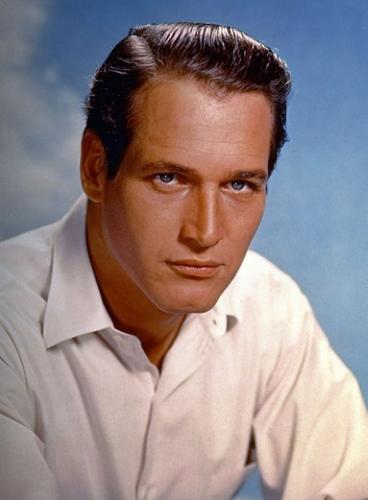

About Paul Newman and the supposed “list”

Let’s handle the headline claim like adults. There is no reliable documentation—video, transcript, contemporary reporting—to confirm that Paul Newman went on CBS Sunday Morning in 1986 and “revealed” that an array of Golden Age actresses were “secretly born male.” Newman was a public figure with decades of press coverage; if he’d said anything remotely like that, it would have generated a paper trail. What he did do in public, repeatedly, was talk about craft, philanthropy, criminal justice reform, and the responsibilities of fame. Turning him into the emcee of a gender outing is fan fiction in bad taste.

Why this rumor keeps breathing

– Myth loves a vacuum. Where archives are thin and the subject guarded, people will write their own documents in the air and swear they saw them in a vault.

– The studio system curated personae so tightly that audiences confuse image with lie. When the spell breaks, some folks go hunting for the “real” person with a scalpel.

– Gender nonconformity still makes people itchy. Rather than admit we’re watching a performance that transgresses rules, rumor tries to retrofit biology into the narrative.

What responsible storytelling looks like here

– Elevate the people who went on record about themselves. Candy Darling and Christine Jorgensen belong at the center of any honest account.

– Read performances as text. Dietrich’s tuxedo is a manifesto, not a confession. Hepburn’s trousers are policy, not clue.

– Refuse medical gossip. Leaked charts, whispered scars, anonymous doctors—this is not reporting; this is violation.

– Keep your skepticism calibrated. Extraordinary claims require more than a decades-later blog post and a fuzzy screenshot.

A quick reality check on the “six names”

The circulating transcript stitches together partly true histories (Candy, Christine) with baroque allegations about Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, and Katharine Hepburn. Those allegations rely on disappearing documents, confiscated records, and unnamed sources that never surface under scrutiny. That doesn’t make the stars less interesting; it makes the rumor less credible. The more shocking the claim, the more boring the proof should be. That’s journalism’s law. When the proof is theatrical, you’re usually watching theater.

What remains, when the smoke clears

– Hollywood has never been straight in the way the studios pretended. The screen has always hosted a spectrum of gender expression. Sometimes coded, sometimes flamboyantly plain.

– The artists we remember bent rules on purpose. Dietrich and Garbo understood that charisma could scramble gender signals and used that scramble to their advantage.

– The costs were real. For Candy Darling, the cost was life lived on a knife’s edge. For Christine Jorgensen, it was dwelling under a microscope. For Crawford and Hepburn, it was defending privacy like a fortress.

– The myths say more about us than about them. Our appetite for a “gotcha” reveal betrays a culture still addicted to policing borders that art has already crossed.

A last word, offered without flourish

If you came here for “No. 4 will shock you,” I’ll disappoint you on purpose. The real story isn’t a reveal. It’s a reckoning: the Golden Age sold illusions, and some of its greatest stars used those illusions to make room for lives that didn’t fit the brochure. That’s not a scandal; that’s the job. We honor it not by inventing conspiracies, but by reading the work, protecting the living, and telling the truth where the record allows.

So, no, Paul Newman didn’t out anyone on Sunday morning television. He didn’t need to. The screen already told you what you needed to know: gender is part costume, part courage, and entirely human. The rest is noise.

News

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius

A Mafia Boss Threatened Dean Martin on Stage—Dean’s Reaction Was Pure Genius Prologue: A Gun in the Spotlight Dean…

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything

The Billionaire Had No Idea His Fiancée Was Poisoning His Son—Until the Maid Exposed Everything Prologue: A Whisper That…

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears

The Billionaire Catches Maid ‘Stealing’ Food… But When He Sees Who It’s For, He Breaks Down in Tears Prologue:…

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid — Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth

The Billionaire’s Fiancée Sets a Trap for the Maid—Until His Silent Daughter Exposed the Truth Prologue: The Whisper That…

The Billionaire Went Undercover as a Gardener — Until the Maid Saved His Children from His Fiancée

Richard Whitmore’s hands trembled on the garden shears as he watched through the kitchen window. His new wife, Vanessa, stood…

Three Flight Attendants Vanished From a Vegas Hotel in 1996 — 28 Years Later a Hidden Wall Is Opened

.Every hotel, every casino, every neon-lit alley has a story, most of them ending in forgetfulness or denial. But some…

End of content

No more pages to load