🌊 Did Polynesians Really Reach America Before Columbus? Shocking DNA Evidence Reveals Secrets of Ancient Navigation That Will Change Everything We Thought We Knew! 🤯

The question of whether ancient Polynesians ever reached the Americas long before Columbus is one of archaeology’s most enduring enigmas.

At the heart of this investigation lies the sweet potato, a crop that should not have been in Polynesia.

When Europeans arrived in the 17th century, they found the islands cultivating this plant, which was native solely to South and Central America.

The existence of the sweet potato across thousands of miles of ocean demanded an explanation—how did it get there? For over three centuries, researchers have debated various theories, from the introduction of the crop by Spanish or Portuguese explorers to the possibility of ocean

currents carrying seeds across the Pacific.

However, neither explanation fully aligns with the linguistic and genetic data available.

The linguistic connection is particularly compelling.

The Polynesian word for sweet potato, “kumar,” closely resembles the term “kumal” used by the Ketwa people in the Andes.

This linguistic parallel suggests more than mere coincidence; it points to direct human contact between these distant cultures.

Language is a powerful vessel for preserving traces of migration, and this shared terminology strongly indicates that a prehistoric connection existed between the Pacific Islands and the Americas.

If confirmed, such contact would radically alter the timeline of human exploration, suggesting that Polynesians, navigating only by stars, waves, and environmental cues, may have achieved trans-oceanic travel centuries before European nations developed comparable methods.

The evidence continues to mount.

Archaeological excavations in Polynesia, particularly on Rapanui (Easter Island) and in New Zealand, have uncovered preserved sweet potatoes dating back to the 13th century—200 years before Columbus.

Carbon dating confirmed these pre-European origins, and the plant itself could not have drifted naturally; its tubers decay quickly in saltwater, and its seeds lack the resilience for long-distance dispersal.

The only viable explanation is deliberate human transport, suggesting that someone carried and cultivated the sweet potato across the Pacific.

Adding to this conclusion is the linguistic evidence that shows the word “kamar” appears across multiple Polynesian languages with minimal variation.

In South America, terms like “kimal” and “kamar” describe the same crop among the Qua and Imara peoples.

The absence of Iberian influence in the naming indicates that the plant was part of an earlier exchange between these cultures, predating European expansion.

This linguistic trail, supported by archaeological findings, reveals significant interaction between these distant societies across the world’s largest ocean.

Despite this mounting evidence, skepticism persists.

Many scholars doubt that Polynesians, lacking metal tools or modern navigation techniques, could have made such a journey to South America and back.

The journey spans thousands of kilometers through unpredictable conditions.

Yet, modern data on carbon dates, crop genetics, and human DNA studies contradict these doubts, solidifying the sweet potato’s role as evidence of ancient trans-oceanic contact.

It demonstrates that isolation was never absolute and that prehistoric exploration linked continents once thought to be separate.

Recent molecular studies of the sweet potato itself have deepened this mystery.

Genetic analyses have reportedly identified strains in Polynesia that are genetically closer to South American varieties than to any Asian species.

This confirms that the plant’s origin is American, not a product of convergent evolution.

The distribution pattern of the sweet potato matches known routes of Polynesian expansion, suggesting intentional dispersal rather than random drift.

The question remains: how did Polynesians manage to sail across the vast Pacific without modern naval technology? The answer lies in their remarkable maritime capabilities.

Around a thousand years ago, the Samoans developed advanced double-hulled canoes, designed for long-distance ocean travel.

These vessels, known as “vatelle,” were engineered for balance, endurance, and cargo capacity.

Polynesian navigation was based on empirical observation and generational memory.

Navigators identified the direction of waves, cloud patterns, and bird flight paths to detect islands beyond the visible horizon.

Stellar navigation was central, with each star’s rise and set used to find precise bearings across open water.

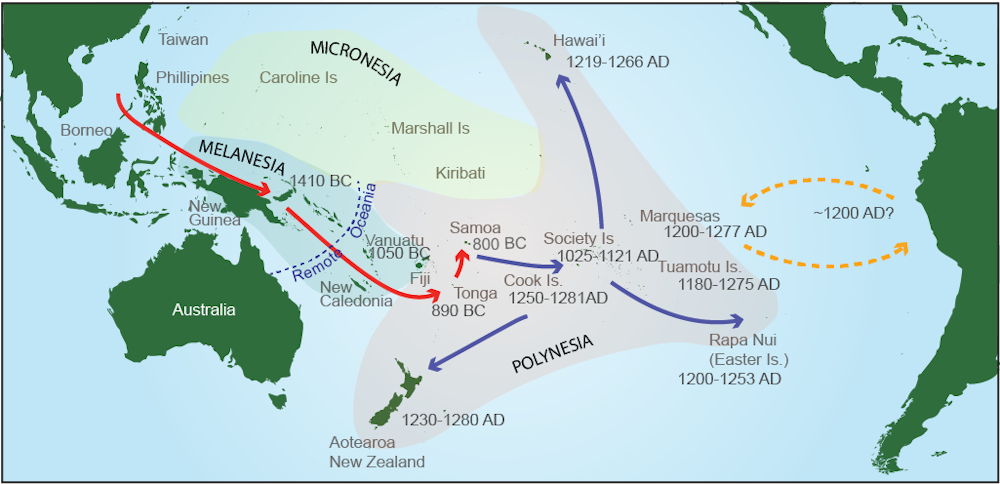

From Samoa, these voyagers expanded eastward to the Cook Islands, Tahiti, and ultimately to Hawaii, New Zealand, and Rapanui.

This migration represents one of humanity’s greatest geographic dispersals, encompassing millions of square miles.

These journeys were intentional and organized, with navigators memorizing thousands of environmental indicators, seasonal winds, and ocean currents.

Expeditions carried plants, animals, and tools to ensure survival and settlement on new islands.

Oral traditions preserved these migrations for centuries, describing ancestral homelands in the west and voyages toward unknown lands in the east.

The archaeological record supports this narrative, with finds of stone adzes identical in form across multiple island chains, indicating technological continuity over thousands of kilometers.

Traces of obsidian tools reveal established exchange routes between far-flung communities.

The design of canoe sails evolved to harness prevailing winds and currents, showcasing a deep understanding of aerodynamics long before Western science defined it.

These were not accidental wanderers but deliberate explorers, trained through decades of apprenticeship, embedding astronomical and oceanographic data into their mental maps.

But did their journeys extend beyond the Pacific all the way to the American continent? The evidence suggests they did.

The sweet potato, along with linguistic parallels, points toward a prehistoric connection between these two regions.

The strongest evidence comes from agricultural remains, which indicate that Polynesians cultivated the sweet potato long before European contact.

This planting was not a novelty but a staple integrated into local farming systems centuries earlier.

News

🔍✨ Unlocking the Secrets of the Herculaneum Scrolls: How AI Decoded Ancient Texts Buried for 2,000 Years—And What It Means for History!

🔍✨ Unlocking the Secrets of the Herculaneum Scrolls: How AI Decoded Ancient Texts Buried for 2,000 Years—And What It Means…

🚨 Is Earth in Danger? NASA & Harvard Reveal 4,000 New Meteors Escorting 3I/ATLAS—The Truth Behind This Cosmic Threat! 🌍

🚨 Is Earth in Danger? NASA & Harvard Reveal 4,000 New Meteors Escorting 3I/ATLAS—The Truth Behind This Cosmic Threat! 🌍 On June…

🎬 Ron Howard SHOCKS Hollywood by Revealing the Dark Secrets of Its Most Notorious Stars—You Won’t Believe Who Made the List! 😱

🎬 Ron Howard SHOCKS Hollywood by Revealing the Dark Secrets of Its Most Notorious Stars—You Won’t Believe Who Made the…

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Audie Murphy’s Mysterious Death—Was It Really an Accident or Something More Sinister? 🔍

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Audie Murphy’s Mysterious Death—Was It Really an Accident or Something More Sinister? 🔍 The tale…

💔 Tom Cruise’s Daughter Suri Null FINALLY SPEAKS OUT—The SHOCKING Truth Behind Their Distance Will Leave You Speechless! 😱

💔 Tom Cruise’s Daughter Suri Null FINALLY SPEAKS OUT—The SHOCKING Truth Behind Their Distance Will Leave You Speechless! 😱 The…

🎭 Russell Crowe SPILLS the TRUTH About Tom Cruise—Fans Are SHOCKED by Their Complicated History! 😲

🎭 Russell Crowe SPILLS the TRUTH About Tom Cruise—Fans Are SHOCKED by Their Complicated History! 😲 Russell Crowe and Tom…

End of content

No more pages to load