📜 The Hidden Truth of Human Existence: Assyriologist Andrew George Breaks His Silence on the Epic of Gilgamesh—What He Reveals Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew! 😲

The Epic of Gilgamesh is often celebrated as one of the earliest works of literature, a narrative that has captivated scholars and readers alike for centuries.

The story, which revolves around the quest of Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk, for immortality following the death of his beloved friend Enkidu, has been interpreted in various ways.

However, Andrew George, a prominent Assyriologist, presents a more ominous perspective on this ancient tale.

He argues that rather than simply recounting the adventures of a mighty king, the epic serves as a profound warning about the perils of human ambition and the quest for eternal life.

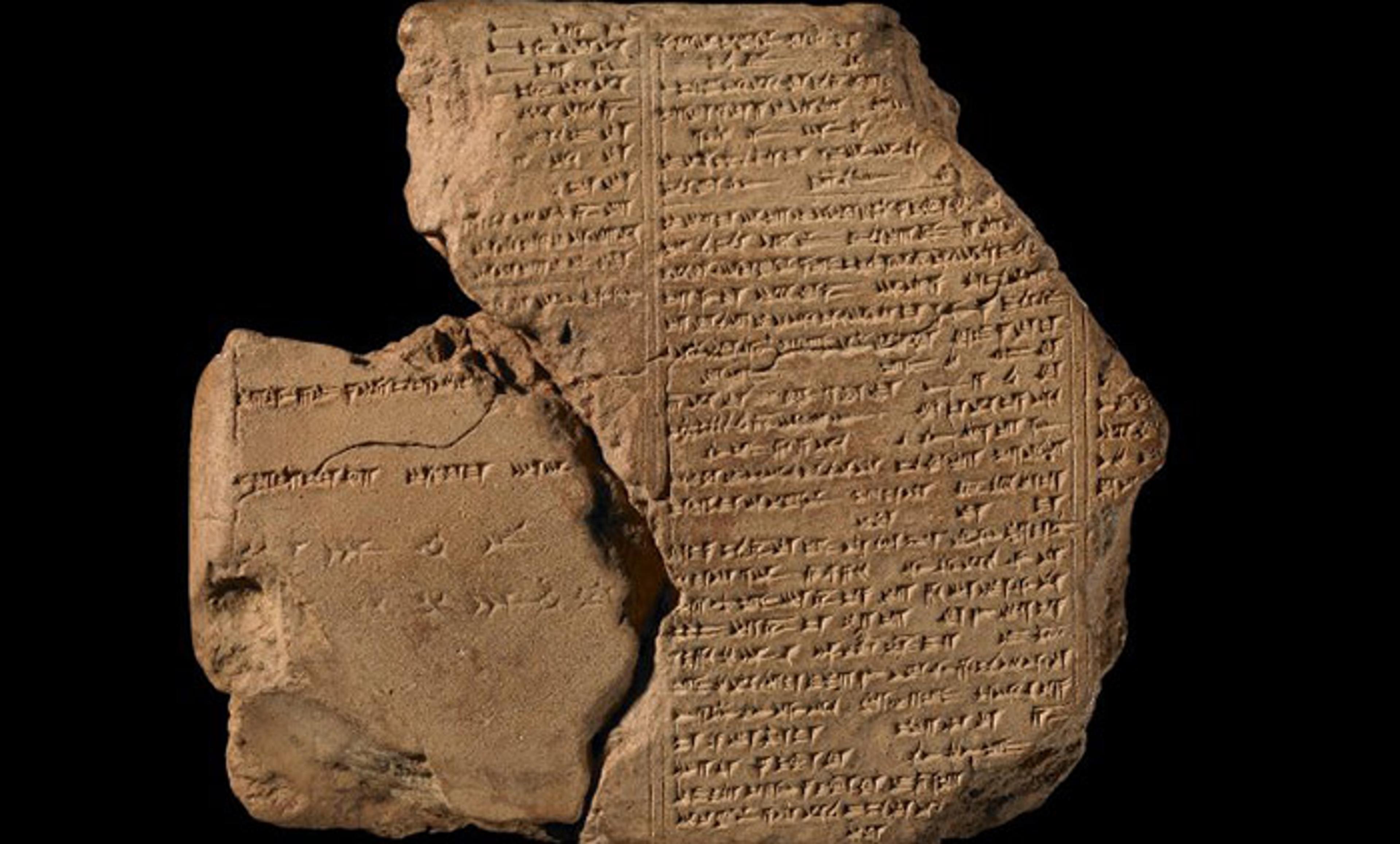

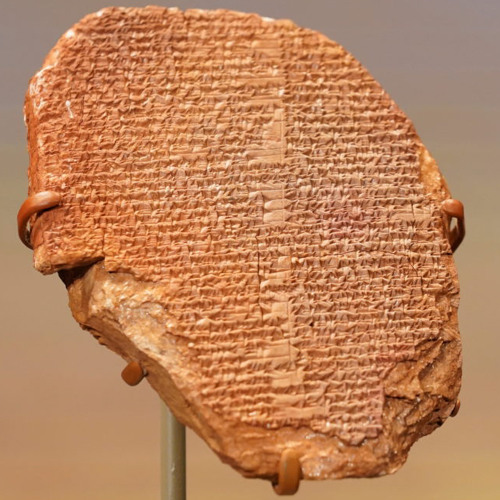

The origins of the Epic of Gilgamesh can be traced back to the ruins of ancient Mesopotamia, specifically to the library of Ashurbanipal, discovered in the mid-19th century.

This library, filled with thousands of clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform writing, contained fragments of stories that had been passed down through generations.

When British explorer Austin Henry Layard unearthed these tablets, he could not have known the significance of what lay beneath the sands of Iraq.

Among these ancient texts, George Smith, a self-taught museum assistant, would later find the account of a great flood, strikingly similar to the biblical story of Noah’s Ark but predating it by millennia.

This revelation shocked the Victorian world, challenging the notion that the biblical texts held the oldest accounts of creation and destruction.

Andrew George emphasizes that the tablets contain knowledge too specific to be mere myth.

They offer detailed accounts of creation, destruction, and the limits imposed on human existence.

The astronomical references embedded in the text hint at advanced understanding of the cosmos, suggesting that the ancients possessed knowledge that has been overlooked or forgotten.

For George, the Epic of Gilgamesh is not just a narrative; it is a warning about the consequences of humanity’s hubris.

The moment we reopened the door to these ancient texts, we unearthed knowledge that was perhaps meant to remain buried.

As George delves deeper into the epic, he uncovers themes that resonate with modern existential dilemmas.

The story does not begin with a creation myth; instead, it introduces Gilgamesh as a ruler already in power, embodying a blend of divine and human traits.

This portrayal challenges the later biblical conception of humanity as a pure creation of a single god.

Instead, the Mesopotamian view presents humans as beings of mixed origins, grappling with the duality of their existence.

The narrative reveals that even a king like Gilgamesh, who possesses everything, is ultimately unfulfilled—a reflection of the human condition itself.

The relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu serves as a focal point in the narrative, highlighting the complexities of friendship, mortality, and the quest for meaning.

When Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh’s grief propels him on a journey to seek eternal life, leading him to confront the gods and the realities of existence.

George posits that this quest is not merely a search for immortality but an exploration of the limits of human ambition.

The gods, portrayed as jealous overseers, resent the growing strength of humanity, and their wrath results in Enkidu’s death—a punishment that underscores the precarious balance between human aspiration and divine authority.

The epic’s exploration of death and sacrifice resonates deeply with George, who believes that it reflects a fundamental truth about existence.

The gods feed on the scent of sacrifices, and the act of remembering the dead becomes a means of keeping the divine presence alive.

This cyclical relationship between life, death, and memory raises unsettling questions about the nature of existence.

If the gods derive sustenance from human suffering and sacrifice, then what does that imply for humanity’s understanding of mortality?

The haunting nature of the Epic of Gilgamesh extends beyond its narrative; it permeates the lives of those who study it.

George Smith’s tragic death, along with the strange experiences reported by subsequent scholars, hints at a deeper connection between the text and the human psyche.

Andrew George himself experienced a profound transformation while translating the tablets, feeling as though the text had a will of its own.

His reflections on the act of translation reveal a sense of possession, where the ancient words seem to reshape the translator’s identity.

The epic’s narrative culminates in the enigmatic twelfth tablet, where Enkidu appears to return from the dead, challenging the boundaries between life and death.

This interruption in the story raises profound questions about the nature of existence and the possibility of defying cosmic law.

George argues that this moment is not merely a resurrection but an intrusion, a testament to the enduring power of human connection even in the face of mortality.

The rumored thirteenth tablet, which allegedly contains reversed text meant to be read only in reflection, adds another layer of complexity to the epic’s legacy.

Linguists suggest that its message could serve as a warning to those who seek to extract meaning from ancient words.

George’s refusal to dismiss the tablet as authentic reflects his understanding of the delicate relationship between the living and the dead, and the potential consequences of engaging with texts that were never meant for mortal eyes.

As Andrew George reflects on the implications of the Epic of Gilgamesh, he warns that humanity’s relentless pursuit of immortality mirrors the tragic fate of its first great hero.

The modern obsession with technology, artificial intelligence, and the desire to transcend human limitations echoes Gilgamesh’s quest for eternal life.

George implores us to recognize that the epic’s message is not merely a relic of the past but a cautionary tale for the present and future.

In his final public lectures, George’s urgency became palpable as he implored his audience to listen—to heed the warnings embedded within the ancient text.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, he argues, is not just a story about mortality; it is a reflection of our own existential struggles.

The gods, who thrive on human grief and sacrifice, remind us that death gives life its value.

Without it, our pursuits lose their significance, and the cycle of existence becomes meaningless.

As we navigate the complexities of modern life, George’s insights compel us to confront the uncomfortable truths about our own mortality.

The Epic of Gilgamesh endures not merely as a story of the past but as a living testament to the human experience—a reminder that our quest for immortality may ultimately lead to our downfall.

As we seek to understand the lessons of Gilgamesh, we must acknowledge the delicate balance between ambition and acceptance, life and death, and the enduring power of memory.

In the end, Andrew George’s plea resonates: before we die, we must listen to the echoes of the past and the warnings they hold for our future.

News

🔍✨ Unlocking the Secrets of the Herculaneum Scrolls: How AI Decoded Ancient Texts Buried for 2,000 Years—And What It Means for History!

🔍✨ Unlocking the Secrets of the Herculaneum Scrolls: How AI Decoded Ancient Texts Buried for 2,000 Years—And What It Means…

🚨 Is Earth in Danger? NASA & Harvard Reveal 4,000 New Meteors Escorting 3I/ATLAS—The Truth Behind This Cosmic Threat! 🌍

🚨 Is Earth in Danger? NASA & Harvard Reveal 4,000 New Meteors Escorting 3I/ATLAS—The Truth Behind This Cosmic Threat! 🌍 On June…

🎬 Ron Howard SHOCKS Hollywood by Revealing the Dark Secrets of Its Most Notorious Stars—You Won’t Believe Who Made the List! 😱

🎬 Ron Howard SHOCKS Hollywood by Revealing the Dark Secrets of Its Most Notorious Stars—You Won’t Believe Who Made the…

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Audie Murphy’s Mysterious Death—Was It Really an Accident or Something More Sinister? 🔍

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Audie Murphy’s Mysterious Death—Was It Really an Accident or Something More Sinister? 🔍 The tale…

💔 Tom Cruise’s Daughter Suri Null FINALLY SPEAKS OUT—The SHOCKING Truth Behind Their Distance Will Leave You Speechless! 😱

💔 Tom Cruise’s Daughter Suri Null FINALLY SPEAKS OUT—The SHOCKING Truth Behind Their Distance Will Leave You Speechless! 😱 The…

🎭 Russell Crowe SPILLS the TRUTH About Tom Cruise—Fans Are SHOCKED by Their Complicated History! 😲

🎭 Russell Crowe SPILLS the TRUTH About Tom Cruise—Fans Are SHOCKED by Their Complicated History! 😲 Russell Crowe and Tom…

End of content

No more pages to load