😱 A Swarm of Comets is Racing into the Inner Solar System with 3I/Atlas 😱

A swarm of comets, plus the interstellar visitor 3I/Atlas, are all closing in on the sun within just 30 days of October 2025.

Astronomers typically expect maybe two or three bright comets a year, but this time, the lineup consists of seven, all at once, including a visitor from another star system on a hyperbolic path.

Is it a cosmic coincidence, a natural clustering never seen in modern records, or does the data hint at something more?

The odds, the origins, and the world’s only past 3I/Atlas set the stage for a discovery that could rewrite what we know about randomness in the solar system.

So, what’s actually driving this wave?

Is it an unseen hand or the wildest celestial jackpot in living memory?

When a comet plunges toward the sun, a quiet transformation begins.

At first, it is nothing more than a frozen speck—ice and dust locked together, orbiting in the deep cold of space.

But as the comet draws closer, sunlight grows fierce.

This is perihelion—the moment of closest approach—when the sun’s heat is most intense and the comet’s true nature is revealed.

At perihelion, a comet’s surface can warm by hundreds of degrees in just a matter of days.

Ice buried beneath the crust begins to sublimate, turning into gas.

Water, carbon dioxide, and ammonia vaporize, building pressure that cracks open the surface and erupts in jets of vapor and dust into space.

These jets do not just sculpt the comet’s appearance; they can also nudge its path ever so slightly, tweaking the orbit by fractions of a second.

For most comets, these changes are minute, but they are a signature of just how dynamic these objects become as they race past the sun.

The result is a coma—a glowing envelope of gas and dust that can swell to tens of thousands of kilometers across.

Sunlight scatters off this cloud, making the comet visible even from Earth.

The coma is the source of the comet’s brightness, measured in magnitude.

Astronomers use this scale to track how easily a comet can be seen.

Lower numbers indicate brighter objects.

For a comet to be visible to the naked eye, it needs to reach about magnitude 6 or lower.

Many comets never reach that brightness, fading into the background or getting lost in the sun’s glare.

But when conditions are right, a comet can outshine the stars, dominating the night sky with its ghostly glow.

Then there are the tails—two distinct kinds, each shaped by different forces.

The dust tail, broad and curved, forms as sunlight pushes tiny grains away from the coma.

It reflects yellow-white light, arcing gently along the comet’s path.

The ion tail is a sharper, bluer streak carried straight back by the solar wind.

This stream of charged particles sweeps molecules away at high speed, sometimes causing the tail to snap or disconnect entirely during solar storms.

Both tails point away from the sun, but their angles and colors reveal what is happening at the heart of the comet.

Every approach is a race between heat and time.

Some comets flare up, then fragment or fade before they are ever seen from Earth.

Others survive the encounter, looping back into the dark for another orbit, sometimes centuries later.

But for the brief window around perihelion, every comet becomes a laboratory.

Its brightness and tails record the invisible dance between ice, rock, and sunlight.

The language of magnitude, the drama of jets and tails—these are the clues astronomers use to predict which comets will become legends and which will vanish without a trace.

On Mount Aloha’s dark slopes, Atlas (short for Asteroid Terrestrial Impact Last Alert System) keeps watch for intruders.

In May 2025, it flagged C/2025K1, a comet brightening fast with perihelion set for October 8th.

Early projections showed a risky solar pass, a possible breakup, and a magnitude just above 5.2—enough for binoculars.

Atlas’s alert was only the beginning.

In September, the SWAN instrument aboard SOHO caught C/2025R2.

SWAN specializes in ultraviolet, spotting comets by their hydrogen emissions.

This one promised a close approach, just 0.27 astronomical units from Earth, peaking around October 21st.

Its southern trajectory and forecast magnitude of four raised hopes for a naked-eye show if its activity held.

Stereo, usually tracking solar storms, found 414P, a faint, fast sungrazer.

These comets skim the sun, risking disintegration before swinging away.

Each comet is distinct, but all are converging on the same days.

The Mount Lemmon survey above Tucson contributed C/2025A6, or Lemon, a periodic visitor with a mapped orbit.

Lemon’s perihelion also falls on October 21st, overlapping with SWAN.

Its brightness is unpredictable; some models suggest magnitude 3, while others estimate as faint as 8.

Lemon’s northern path means observers from Europe to Canada will have a clear view.

Pan-STARRS, another Hawaiian survey, added C/2025 K1.

This newcomer isn’t expected to dazzle, but its timing matters for the cluster.

Each comet comes from a different search—robots, solar instruments, ground-based surveys.

Their orbits cross and diverge, yet the calendar keeps drawing them together.

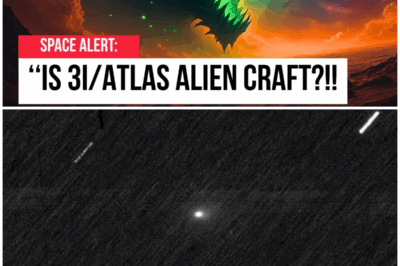

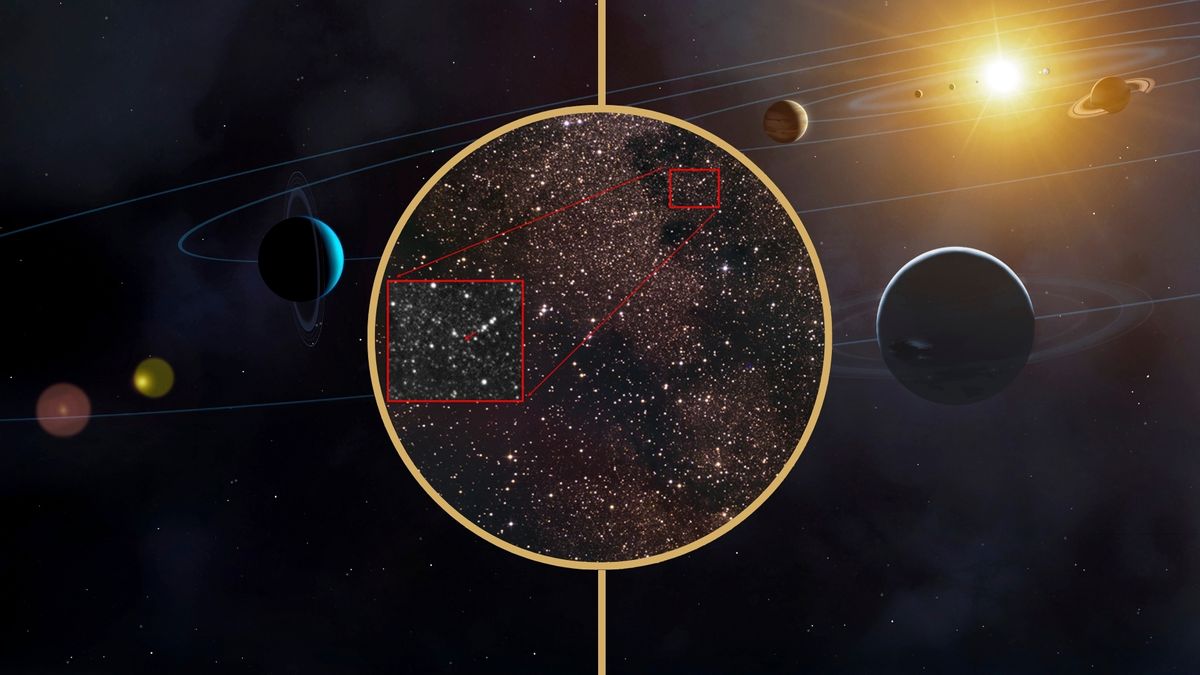

Above them all is 3I/Atlas, the interstellar outlier, spotted by Atlas in July 2025.

Its hyperbolic path and outbound-only trajectory mark it as the third confirmed visitor from beyond our solar system.

Its perihelion falls on October 29th, just after the main group.

Its arrival during this crowded window turns a rare event into something astronomers struggle to quantify.

For the first time, seven named comets—each tracked by a different instrument—will peak within days of each other.

The discovery network stretches from ground to orbit, ultraviolet to visible, weaving a global web of vigilance.

With every new detection, October 2025 grows more crowded, setting the stage for a clustering that resists easy explanation.

In a typical year, the sky offers up its cometary wonders sparingly.

The historical record, stretching back through a century of careful observation, shows a familiar rhythm—two, maybe three comets bright enough for binoculars, each spaced out across the seasons.

Most years pass without any naked-eye spectacle at all.

When a comet does flare into view, it’s usually a solitary performer, not part of a crowd.

Astronomers, both amateur and professional, have grown used to this measured pace—a slow drip of icy visitors, each arrival a minor event in the quiet ledger of the night sky.

Catalogs from the Minor Planet Center and the International Astronomical Union bear this out.

Between 1900 and 2022, the mean number of comets reaching binocular visibility per year hovers just above two.

Some decades, like the 1950s or early 2000s, see brief upswings as new surveys come online or as solar activity stirs up more distant objects.

Yet even with the advent of all-sky search programs like NEAT, Pan-STARRS, and Atlas, the basic cadence holds.

Bright comets remain rare.

Their arrivals are scattered, sometimes separated by months or even years.

The records show only a handful of cases where two comets reach similar brightness within a few weeks of each other.

And those episodes are the stuff of stargazer legend.

The clustering forecast for October 2025 stands out against this backdrop like a lightning bolt on a clear night.

Instead of two or three, the calendar shows seven comets peaking in less than 30 days, including an interstellar interloper.

The numbers strain belief.

Monte Carlo simulations using a century’s worth of perihelion dates and brightness estimates suggest that the odds of six bright comets and an interstellar object all crowding into a single month are less than 1 in 30,000, possibly as rare as 1 in 100,000.

Even after correcting for the improved sensitivity of modern surveys and for the fact that today’s telescopes catch fainter, more distant objects than ever before, the probability barely budges.

The clustering is not a trick of technology; it is, by every statistical yardstick, an outlier.

Astronomical communities noticed the anomaly almost in real-time.

In early 2025, as ephemerides for newly discovered comets were posted to open sky forums, a pattern began to emerge.

Visualization tools, once the province of professionals, let hobbyists overlay orbits and spot the swarm for themselves.

The sense of surprise was palpable.

No one could point to a historical precedent; the archives simply didn’t contain it.

Survey bias, the perennial suspect in any explosion of new discoveries, fails to explain the timing.

While more comets are found now than in the age of photographic plates, the true rate of arrivals, especially for the brightest visible objects, has not changed enough to create this kind of pileup.

Solar activity peaking in 2025 does boost the number of sungrazers and can shake loose a few extra fragments.

But it cannot manufacture a parade of major comets, each on its own distinct path converging in the same month.

The clustering is not just a quirk of how we look; it’s a real physical event written across the sky.

Statistical outliers invite speculation, but they also demand rigor.

The 2025 swarm is a natural experiment—a stress test for every model of cometary arrival and detection.

In the coming months, astronomers will comb the data for hidden connections, shared origins, orbital echoes, and hints of fragmentation in the distant past.

But for now, the numbers speak for themselves.

October 2025 will be a month unlike any other in the history of comet watching—a statistical spike that resists easy explanation and sets the stage for a deeper search for causes.

Statisticians at the International Astronomical Union ran the numbers as soon as the October 2025 lineup became clear.

They turned to Monte Carlo simulations, a digital lottery drawing random comet arrival dates from over a century of observations.

Each run asked the same question: how often do six bright comets plus an interstellar visitor all peak within a single month?

The answer: almost never.

In one million simulated years, the clustering appeared just a handful of times.

The raw odds—less than 1 in 30,000—are so remote that they leave most probability charts gasping for breath.

Survey bias is the first suspect in any statistical surprise.

Modern sky surveys like Atlas, Pan-STARRS, and SWAN sweep the heavens with relentless efficiency, catching faint comets that would have slipped past earlier generations.

But even after adjusting for these sharper eyes, the anomaly barely softens.

The simulations account for every gain in sensitivity and every uptick in discovery rate since the year 2000.

The result: the chance of this many bright, distinct comets crowding into a single month drops even further to less than one in 100,000.

These are odds you would expect from a lottery, not the sky.

Brightness thresholds refuse to play along with simple explanations.

Survey telescopes find more faint comets, but the number of truly bright naked-eye candidates has remained stubbornly steady for decades.

The 2025 cluster is not a parade of marginal objects boosted by better cameras.

It is a convergence of comets that would have stood out in any era, each one crossing the visibility threshold by its own merits.

The historical record, spanning photographic plates, logbooks, and digital catalogs, shows only solitary flares and the rare double act.

Never a gathering like this.

Visualizations from the Minor Planet Center lay out the past century in stark relief.

Most years, the calendar is a sparse grid with comet peaks scattered months apart.

The few times two comets have approached perihelion together, astronomers took note.

Three in a month is a legend.

Seven, including an interstellar outlier, is a statistical spike so sharp it stands alone.

No burst of solar activity, no uptick in survey coverage can conjure this pattern from chance alone.

The numbers, once stacked, refuse to be ignored.

Probability models, detection corrections, and brightness thresholds all point to the same conclusion: the October to December 2025 clustering is not a mirage created by human technology or a statistical fluke.

It is, by every measure, a physical event that strains the boundaries of randomness.

The models leave one question hanging in the air: if chance cannot explain the swarm, what can?

Suppose for a moment that these seven comets are not simply obeying the laws of chance.

What would it take to coordinate their arrival?

Dr. Kevin Blanchard, part of the Atlas Discovery team, lays out the raw numbers.

To herd even two comets onto synchronized paths, let alone seven, would require forces far beyond anything produced by natural jets.

Typical non-gravitational nudges measured by Marsden’s A1, A2, and A3 parameters barely register above 1 millionth of a G.

Natural outgassing can shift a comet’s speed by less than a meter/second over months.

But to compress perihelion windows by days, the required delta V jumps to tens of meters/second—100 times greater than the wildest comet outburst ever recorded.

Artificial shepherding would leave fingerprints—simultaneous outbursts outside solar storm windows, chemical signatures, engineered isotopes, metals, or molecules never seen in natural comets etched into their spectra.

Synchronized orbital changes would be visible as abrupt shared deviations in the post-perihelion solutions.

A smoking gun would be an isotope ratio so unnatural it could only be manufactured, or a non-gravitational acceleration out of family with every known comet.

So far, the data is stubbornly ordinary.

The Marsden parameters for each 2025 comet fall inside the expected range for their size and distance from the sun.

Spectral scans from ground and space show only the familiar fingerprints of water, ice, dust, and simple molecules.

No engineered isotopes, no coordinated outbursts, no signals.

The numbers leave little room for fantasy.

If a hidden hand is at work, it hides better than any technology known to science.

SETI’s latest round of radio sweeps has come and gone without a single artificial signal.

The Allen Telescope Array and Breakthrough Listen teams tracked every major object in the October cluster, focusing especially on 3I/Atlas during its closest approach across the spectrum.

Hours of integration from 1 to 11 GHz revealed no narrowband beacons, no engineered pulses—nothing but the hiss of natural emissions and the usual background.

The silence is as telling as any positive result.

If there’s a message, it’s hidden deeper than our instruments can reach, or it simply isn’t there.

Meanwhile, solar maximum has reached its peak.

Space weather models show a sun bristling with energy, coronal mass ejections, high-velocity solar wind, and magnetic storms that rattle satellites and stretch comet tails to breaking.

Every tail disconnection in the October swarm and every sudden brightening or jet has coincided with a spike in solar activity.

The timeline is tight.

Lemon’s brief outburst tracked a geomagnetic surge measured at Earth.

These are classic signatures of solar-driven drama, not coordinated signals.

No comet in the cluster approaches Earth closer than 0.27 astronomical units—impact risk is zero.

The real-world hazard comes not from icy visitors, but from the sun itself—solar storms that can trip power grids and jam spacecraft.

As the watch list grows, astronomers are lining up coordinated campaigns for spectral scans, astrometric tracking, and open dashboards logging every anomaly.

The rule remains: extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence.

For now, the data holds steady—no artificial accelerations, no engineered molecules, no synchronized maneuvers.

The sky is crowded, but the verdict is clear.

The test continues.

What would change this picture?

A signal, a non-natural isotope, a maneuver no comet could perform.

Until then, skepticism is not just caution; it’s the best tool we have.

Still, the reasons behind such precise timing remain unsolved, as no known mechanism forces unrelated comets to converge in this way.

As new observations come in during solar maximum, scientists will watch for any unexpected changes in spectra, motion, or fragmentation.

For now, the 2025 comet cluster stands as a reminder that our solar system can still surprise us, and every answer sparks new questions.

News

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 – HTT

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 In the world of rock music,…

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 – HTT

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 Ian Gillan, the legendary…

😱 Is 3I/ATLAS a Cosmic Seed or a Galactic Trojan Horse? Prepare to Be Amazed! 😱 – HTT

New Evidence Sheds Light on the Enigmatic 3I/ATLAS: A Cosmic Visitor Defying Expectations Since the dawn of telescopic astronomy, interstellar…

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 What’s the one love song that always melts…

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 Andre Rieu did the unthinkable. He…

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 – HTT

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 Ace Frehley, the legendary guitarist and founding…

End of content

No more pages to load