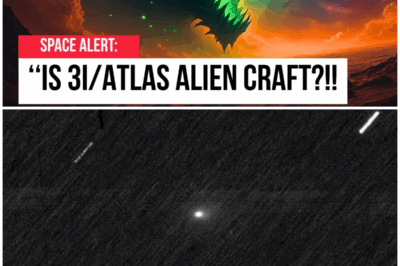

😱 As 3I/Atlas Approaches, Is Our Understanding of Comets About to Be Rewritten? 😱

3I/Atlas is getting too close to the sun right now.

The third ever confirmed interstellar object is racing through the inner solar system, crossing inside Mars’s orbit and surging toward its perihelion at nearly 68 km/s.

But just as the world’s telescopes go blind during a mid-October solar conjunction, Atlas will plunge into the sun’s fierce electric field beyond Earth’s view, leaving every scientist with only guesswork and rising questions about its bizarre chemistry, massive scale, and unpredictable behavior.

What will happen when a possible 50 km object from another star system collides with the solar wind at full speed, invisible to human eyes?

The timeline, the risks, and the unanswered mysteries all start right now.

Currently, this wanderer is carving its own path inside the orbit of Mars, tilted roughly 5° off the ecliptic—a trajectory so steep and retrograde that it slices almost head-on through the plane of the solar system.

The orbital inclination stands at 175°, a number that underscores just how foreign its origins must be.

Most comets and asteroids travel in the same broad direction as the planets, but this one is a true outsider, approaching from the opposite direction and crossing the planetary highway at a sharp angle.

The numbers alone tell a story of relentless acceleration.

When first clocked by the Atlas survey in early July, its velocity was already an impressive 58 km/s.

Now, as it plunges ever deeper toward the sun, that speed climbs steadily on track to reach nearly 68 km/s at perihelion.

Try to picture that: a chunk of interstellar debris, possibly as wide as a medium-sized city, hurtling through the solar system faster than any spacecraft ever built.

At these rates, it covers the distance from Earth to the moon in just over an hour.

Perihelion arrives on October 29th at 11:55 UTC.

The closest approach to the sun will occur at about 1.36 to 1.40 astronomical units, just inside the orbit of Mars, yet still well beyond Earth’s own path.

Unlike the sun grazers that flirt with destruction, this visitor will not dive into the solar corona.

Instead, it skirts the boundary of the inner system, threading a course through the region where solar wind and electromagnetic fields reach their most turbulent.

The geometry places it in the constellation Virgo at closest approach, but from Earth’s perspective, the sun’s glare will render it completely invisible.

The orbital elements cataloged by the Minor Planet Center confirm a hyperbolic trajectory, with an eccentricity greater than one—a mathematical signature that guarantees it will never return.

Its inbound track, outbound escape, and the sharpness of its solar swing all point to a brief, one-time passage.

Every kilometer it travels now is a kilometer closer to the sun’s domain and a kilometer further from the only vantage points capable of tracking its journey.

This is the geometry of a cosmic interloper—inside Mars, 5° off the ecliptic, racing from 58 to nearly 68 km/s with a date with the sun set for October 29th.

The numbers are precise, the timeline is fixed, and the window for direct observation is closing with every passing hour.

From Earth’s vantage point, the calendar grows stark.

October 21st, 2025, brings superior conjunction.

That’s the moment when 3I/Atlas slips directly behind the sun, hidden from every ground-based telescope and even most space observatories.

For the next several weeks, solar glare dominates the sky, drowning out any trace of this interstellar visitor.

Astronomers call it a blackout—an enforced silence where no new data can be gathered, no matter how advanced the equipment.

The sun’s disc acts as a blinding curtain, blocking not only visible light but also most infrared and ultraviolet signals.

Try to imagine the frustration.

After months of urgent coordination, over 120 observing runs, emergency override programs at flagship telescopes, frantic Slack channels, and late-night Zoom calls, the entire global campaign is forced to pause.

The geometry is unforgiving.

Solar elongation—the angle between the comet and the sun as seen from Earth—shrinks to nearly zero.

Even the most ambitious adaptive optics or dusk and dawn hacks fail.

Detectors are at risk of damage, and safety protocols trigger automatic shutdowns.

The last reliable data points trickle in around October 18th as the object’s apparent separation from the sun dips below critical thresholds.

Coronagraphs, those specialized solar observatories designed to block the sun’s blinding core, offer little hope.

At magnitude 12, 3I/Atlas is simply too faint and too compact to stand out against the turbulent brightness of the corona.

Deep background subtraction and stacking techniques, so effective for brighter sunrises, fall short here.

No confirmed detections have surfaced from SOHO, STEREO, Parker Solar Probe, or Solar Orbiter during this window.

Attention briefly turns to Mars.

In early October, orbiters like Mars Express and the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter managed a handful of long exposure images and low-resolution spectra as the comet skimmed past the red planet.

Their vantage point offered a fleeting advantage—one last look before the sun intervened.

Yet even these data sets are limited.

The coma appears as a faint fuzzy dot; the nucleus unresolved, the tail invisible to their sensors.

Attempts to redirect Mars orbiters for perihelion phase imaging spark debate within mission teams.

Resource constraints, orbital geometry, and instrument safety ultimately win out.

The opportunity closes.

So when does the silence break?

The recovery window opens in mid to late November as 3I/Atlas emerges from behind the sun and reclaims a spot in the dawn sky.

By then, it will be receding both in distance and brightness, but still within reach of large telescopes and dedicated amateurs.

The calendar’s next milestone is December 19th, 2025, when the comet makes its closest approach to Earth—about 1.80 astronomical units—just before the winter solstice.

Between conjunction and reacquisition, the story is one of anticipation and uncertainty.

Every hour lost to the sun’s glare is an hour when the most anomalous interstellar object ever recorded could transform, fragment, or simply fade away unseen.

The scientific clock is ticking, and the world waits for the first signal to break through the solar curtain.

Size, in this case, refuses to settle into a single tidy number.

Early photometric readings drawn from dozens of telescopes across both hemispheres suggested a nucleus somewhere between 5 and 50 km wide—potentially the largest interstellar object ever observed.

That range is not a rounding error; it’s a symptom of an object shrouded in its own activity.

The coma, a diffuse envelope of gas and dust, expands so densely around the core that even the most powerful ground-based mirrors and Mars orbiting cameras can’t resolve the true solid body.

Instead, astronomers are left to infer mass and volume from indirect clues: how the object brightens, how its light scatters, and how quickly the coma thickens as it nears the sun.

Color, too, is a story in flux.

Through June and July, the coma’s spectrum leaned red—an indicator perhaps of complex organic grains or larger, slow sublimating particles.

By August, something changed.

The coma shifted to a pronounced green, a hue rarely seen so strongly in solar system comets.

Spectroscopic campaigns, including those with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope and the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, tracked this evolution in real time.

The culprit appears to be an upsurge in carbon-based molecules, especially C2 and CN radicals, unleashed as the comet’s CO2 content vaporized under mounting solar heat.

The green glow is not just a visual oddity; it’s a chemical fingerprint, revealing that CO2, not water, dominates the outgassing.

That alone sets 3I/Atlas apart from most known comets, whose activity is usually driven by water ice.

The chemical portrait grows stranger.

Spectra obtained from both hemispheres and embargoed preprints circulating among specialist teams point toward a nickel-to-iron ratio far outside typical solar system bounds.

Nickel lines, strong and persistent, outshine their iron counterparts by margins that hint at an origin in a supernova remnant or the stripped core of an ancient differentiated planet.

If confirmed, this would rewrite assumptions about what kinds of debris survive the interstellar journey.

The dust itself, as revealed by polarimetric studies, shows extreme negative polarization.

Light is scattered in a way that betrays a preponderance of fine, possibly glassy or metallic grains rather than the silicate material familiar from local comets.

Morphology is yet another puzzle.

Instead of a classic anti-solar tail, 3I/Atlas sports a coma that is brightest on the sunward side, with a forward scattering envelope that defies standard models of dust and gas flow.

The sun-facing edge gleams with a density and texture that has prompted heated debate among observers.

Some argue for a jetting phenomenon; others for a sheath of highly reflective metal-rich dust.

The anti-solar tail, if present, remains faint and elusive—a mere whisper against the glare.

The light curve, tracked obsessively in the weeks before solar conjunction, adds urgency to the mystery.

Instead of fading as expected, the comet’s brightness climbed steadily even as it crossed the orbit of Mars and entered the sun’s domain.

This pre-gap brightening recorded in the final days before the data blackout fueled a storm of speculation across every observer channel.

Was it a sign of fragmentation, a new outburst of volatile gas, or simply the unveiling of fresh surface layers never before touched by sunlight?

Each anomaly—size, color, chemistry, polarization, coma, geometry—has drawn the attention of a sprawling, loosely coordinated observer community.

Professional astronomers, amateur sky watchers, planetary scientists, and instrument specialists have converged in digital forums, racing to decipher the object’s secrets before technical limits and the sun’s glare impose silence.

Their findings, arguments, and unanswered questions now set the stage for a deeper confrontation with the limits of our instruments and the boundaries of current cometary science.

Magnitude 12—that’s the predicted brightness of 3I/Atlas as it sweeps behind the sun, fainter than any planet and far below the detection threshold of most solar observatories.

For instrument engineers and data analysts, that single number defines the practical boundary between wishful thinking and real measurement.

Coronagraphs like SOHO’s LASCO C3 or STEREO’s Heliospheric Imager are built to block the sun’s glare and reveal dramatic outbursts, but their detectors are tuned for objects at least 100 times brighter than this interstellar visitor.

Even with heroic digital processing, the surface brightness of the coma falls short.

The comet’s angular size, just a few arcseconds at best, renders it indistinguishable from the background noise of the solar corona.

No confirmed detections have surfaced from any solar-focused spacecraft—not from SOHO, not from STEREO, not from Parker Solar Probe, not from Solar Orbiter.

The standard data products—those daily movies of the inner solar system—show nothing but turbulent plasma and the occasional planet.

For 3I/Atlas, the signal-to-noise ratio remains stubbornly below one, even when stacking dozens or hundreds of images.

The coma’s faint diffuse glow is simply overwhelmed by the ever-changing light patterns that surround the sun.

Some teams propose a workaround—shift and stack.

The concept is elegant in theory.

Take hundreds of images, predict the comet’s apparent motion across the detector, and digitally align each frame so that any faint moving object adds up while static background features cancel out.

On paper, this method can push the detection limit down by a full magnitude or two.

In practice, it demands an accurate ephemeris, precise knowledge of the comet’s path, and a willingness to wade through terabytes of noisy data in search of a single faint smudge.

For 3I/Atlas, even the most optimistic shift-and-stack campaigns—100 frames from LASCO, 50 from STEREO—still fall short of a secure detection.

The math is unforgiving.

The expected gain in signal-to-noise is swamped by the sheer faintness and compactness of the coma.

Instrument safety protocols introduce another barrier.

As the comet’s solar elongation drops below critical angles, automatic shutdowns kick in to protect sensitive detectors from accidental exposure to the sun’s disc.

No amount of manual override can justify risking a billion-dollar imager for a target that may not even be visible.

For ground-based telescopes, the situation is even more stark.

The sun’s glare saturates the sky, and no amount of adaptive optics or horizon skimming can pull the comet out of the haze.

Mars orbiters offered a brief glimmer of hope.

Their unique vantage point allowed for a handful of long exposure images in early October.

But by the time perihelion arrived, their orbital geometry and instrument constraints closed that window.

No high-end telescope on Earth, in orbit, or circling Mars remained in position to watch the critical moment when solar heating peaked.

For now, the data gap is absolute.

The world’s best coronagraphs and heliophysics images are forced to admit defeat.

3I/Atlas is simply too dim, too small, and too close to the sun for any direct measurement during conjunction.

The only path forward lies in creative data mining, reprocessing old exposures, stacking images along predicted tracks, and holding out hope for a post-conjunction surprise.

Instrument teams are already sketching out contingency plans for future interstellar visitors—more flexible safing protocols, dedicated shift-and-stack pipelines, and perhaps one day, solar observatories designed to chase faint comets through the glare.

For now, the boundaries are clear.

The object is out there, racing unseen, and the instruments built to catch it have met their match.

The moment 3I/Atlas swings closest to the sun, a new set of questions comes into sharp focus—questions that stretch beyond standard cometary models.

Among the most vocal are advocates for electromagnetic explanations—the so-called electric universe theorists—who argue that comets are not just icy relics but dynamic players in the solar plasma environment.

For them, perihelion is more than a gravitational checkpoint; it’s a natural laboratory where the solar wind, electric fields, and charged dust could interact in ways that leave measurable fingerprints.

One hypothesis on the table: a sudden outburst of activity triggered not by heat alone, but by the object’s plunge through regions of intense electromagnetic flux.

If the coma’s carbon dioxide-rich dust is electrically charged, the sun’s field could accelerate particles, alter the coma’s shape, or even shift the trajectory by a detectable margin.

Effects that would show up as small but real deviations in post-perihelion tracking.

Dusty plasma specialists are already drafting diagnostic metrics—changes in coma polarization, unexpected drifts in the outbound path, or a burst of radio emission as solar wind slams into the dense metal-rich envelope.

No one is claiming certainty.

These are testable predictions, not declarations.

When 3I/Atlas reappears in November, every new data point—brightness, position, coma, structure—will serve as a diagnostic for mission planners and alternative theorists alike.

The next phase is a waiting game, with the hope that nature might deliver a verdict on ideas long considered fringe.

Astrologers tracking the sky at perihelion note a rare convergence.

As 3I/Atlas threads the constellation Virgo, it stands in direct opposition to Chiron, with Aerys nearby while Jupiter and Pluto form their own axis across the heavens.

Chart watchers read these alignments as a grand cross overlaid with kite and grand trine motifs, which have long been associated with crisis, transformation, and the search for deeper purpose.

Some interpret the comet’s passage through Virgo as a symbol of healing through disruption—a reminder that even the most alien visitor can stir ancient patterns of reflection and renewal.

For those who follow planetary cycles, the timing resonates.

3I/Atlas makes its closest pass by Earth just before the winter solstice—a season marked by darkness turning toward light.

The outbound journey brings the traveler into a close encounter with Jupiter by March—a progression that, in astrological tradition, hints at the possibility of new beginnings and shifting collective priorities.

Whether these patterns are read as cosmic metaphor or simple coincidence, they offer a bridge between scientific observation and human meaning-making.

For viewers who want to mark the occasion, a commemorative design is available.

The story of 3I/Atlas continues, woven from both data and dreams.

As the world waits for its return to view, key questions persist.

What drives its anomalous behavior?

Will perihelion trigger changes in activity or trajectory?

These answers await its reappearance in mid to late November.

As the data gap continues, each new observation of 3I/Atlas will test our understanding of interstellar visitors and the limits of solar system science.

For now, only the archival record stands—a reminder of how much remains hidden, even as the evidence grows.

News

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 – HTT

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 In the world of rock music,…

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 – HTT

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 Ian Gillan, the legendary…

😱 Is 3I/ATLAS a Cosmic Seed or a Galactic Trojan Horse? Prepare to Be Amazed! 😱 – HTT

New Evidence Sheds Light on the Enigmatic 3I/ATLAS: A Cosmic Visitor Defying Expectations Since the dawn of telescopic astronomy, interstellar…

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 What’s the one love song that always melts…

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 Andre Rieu did the unthinkable. He…

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 – HTT

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 Ace Frehley, the legendary guitarist and founding…

End of content

No more pages to load