😱 Hubble’s “Best Shot” Was Just a Teaser – James Webb’s Universe Is 80 Times Wilder! 😱

James Webb Space Telescope Unveils the True Scale and Complexity of the Universe

In 2004, the Hubble Space Telescope captured an image known as the Ultra Deep Field, targeting a seemingly empty patch of sky. Over nearly two weeks, Hubble collected faint light signals from distant galaxies, revealing about 10,000 galaxies in an area smaller than a tenth of the full moon’s size. This image was a monumental achievement, offering a glimpse into the universe’s adolescence and the formation of early galaxies over 13 billion years ago.

Hubble’s Ultra Deep Field became a defining snapshot for astronomers, capturing spiral galaxies, ancient ellipticals, and early star-forming blue clumps. However, the image had limitations. Hubble’s 2.4-meter mirror, while powerful, could only gather a fraction of the light from the faintest, most distant galaxies. Its sensitivity was strongest in visible and ultraviolet wavelengths but diminished in the infrared spectrum, where ancient light is stretched due to the universe’s expansion.

Another major obstacle was cosmic dust. Thick clouds of dust from early star formation obscured many galaxies, preventing Hubble from revealing their true numbers or environments. Moreover, the Ultra Deep Field covered a narrow, pencil-thin slice of the cosmos, offering a limited view that left astronomers questioning whether the galaxies seen were rare or part of a larger population.

The arrival of the James Webb Space Telescope marked a paradigm shift. Equipped with a massive 6.5-meter gold-coated mirror—nearly three times wider than Hubble’s—and instruments optimized for infrared observation, JWST was designed to peer deeper into the cosmos than ever before. Infrared light, stretched by cosmic expansion, reveals galaxies hidden behind dust and time, invisible to Hubble’s eyes.

JWST’s near-infrared camera and mid-infrared instruments can detect wavelengths from 0.6 to 28 microns, allowing astronomers to see galaxies formed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. These tools not only penetrate dust clouds but also capture the glow of cold dust and newborn stars, transforming gaps in cosmic knowledge into detailed records of history.

Astronomers Caitlyn Casey and Jhan Cartalte spearheaded a new survey approach that combined depth and breadth to map galaxies and their environments with unprecedented precision. JWST’s segmented mirror alignment and ultra-cold detectors enabled the capture of thousands of overlapping exposures, stitched into a continuous mosaic covering about half a square degree—roughly the size of three full moons side by side.

This survey, known as the Cosmos Web, cataloged nearly 780,000 galaxies—an 80-fold increase in area compared to Hubble’s Ultra Deep Field, yet nearly as deep. Each galaxy in this vast dataset is a real system with stars, gas, and a unique history, some dating back over 13.5 billion years to when the universe was less than 300 million years old.

The Cosmos Web survey revealed entire populations of galaxies previously invisible. Massive, red, and dusty galaxies that Hubble missed now fill the frame. Even the faintest smudges, once hidden behind dust or stretched beyond visible light, are now cataloged and studied. This comprehensive atlas reveals not just isolated galaxies but the grand architecture of the universe—filaments, clusters, and voids stretching across millions of light years.

Filaments act as cosmic highways, channeling matter into dense knots where galaxy clusters form. Galaxies along these threads interact, sometimes merging or passing close by, while clusters blaze with thousands of galaxies packed tightly together. These interactions trigger bursts of star formation or, conversely, quench it entirely.

In contrast, vast voids between filaments are regions so empty that galaxies drift alone for billions of years. The Cosmos Web mosaic allows astronomers to study how a galaxy’s environment influences its evolution. Spirals with graceful arms tend to reside in quieter regions, while irregular and colliding galaxies cluster in dense filaments or core clusters, shaped by gravitational tides.

The survey’s depth and breadth reveal environmental trends: star-forming galaxies line filaments, while clusters serve as laboratories of transformation. Some massive galaxies, already quenched, cluster densely, hinting at how cosmic neighborhoods influence galaxy life cycles. This connected, evolving cosmic landscape challenges prior views of the universe as isolated islands.

Among the most dramatic discoveries is the “Infinity Galaxy,” a pair of colliding disc galaxies nearly 8 billion light years away. At their core lie not two but three supermassive black holes—two at the galactic centers as expected, and a surprising third off-center, embedded in shocked gas. This off-nuclear black hole likely formed directly in the merger debris, challenging conventional models of black hole growth that require slow assembly.

Other anomalies abound. During the so-called cosmic noon, about 10 billion years ago, theory predicted a universe dominated by young, chaotic, starburst galaxies. Instead, JWST revealed massive galaxies already quenched and red, as well as mature spiral discs and barred structures appearing much earlier than expected. These galaxies rotate calmly, defying models that expect turbulence at such early epochs.

These findings suggest galaxies matured and organized themselves far faster than current theories allow. The processes that shut down star formation must have been earlier and more efficient than previously believed. Each discovery—from off-center black holes to premature galaxy maturity—demands a fundamental rethink of cosmic evolution.

JWST also identified record-breaking early galaxies, such as Jade’s GSZ14 and MOMZ14, whose light began traveling just 280 to 290 million years after the Big Bang. Spectroscopic signatures confirm their extreme distances. Remarkably, oxygen emission lines detected in Jade’s GSZ14 indicate that at least one generation of massive stars had already lived and died, enriching the universe with heavier elements far earlier than anticipated.

This rapid chemical enrichment shows the early cosmos was a crucible of intense star formation and recycling, not a slow, simple beginning. The Cosmos Web discoveries have upended timelines, revealing a universe where galaxies grew massive, matured, and ceased star formation at breakneck speed. The evidence points to a faster reionization, rapid dark matter halo assembly, and accelerated black hole seeding.

Despite JWST’s unprecedented insights, the Cosmos Web field covers only a tiny fraction of the sky. The universe’s true scale and complexity remain vast and elusive, hinting at even greater cosmic mysteries. Every answer raises new questions: How did discs stabilize so quickly? What drove such early quenching? The astronomical community is racing to explore these puzzles with wider JWST mosaics and complementary observatories like ALMA.

The universe has revealed new layers of complexity, but the quest to understand its origins is far from over. As JWST continues to map the cosmos, it forces scientists to rethink everything they thought they knew about galaxy formation, black hole growth, and the grand architecture of the universe.

The real frontier is not just distance—it is the speed at which we must rewrite the cosmic story.

News

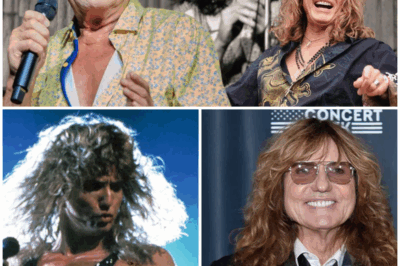

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 – HTT

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 In the world of rock music,…

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 – HTT

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 Ian Gillan, the legendary…

😱 Is 3I/ATLAS a Cosmic Seed or a Galactic Trojan Horse? Prepare to Be Amazed! 😱 – HTT

New Evidence Sheds Light on the Enigmatic 3I/ATLAS: A Cosmic Visitor Defying Expectations Since the dawn of telescopic astronomy, interstellar…

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 What’s the one love song that always melts…

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 Andre Rieu did the unthinkable. He…

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 – HTT

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 Ace Frehley, the legendary guitarist and founding…

End of content

No more pages to load