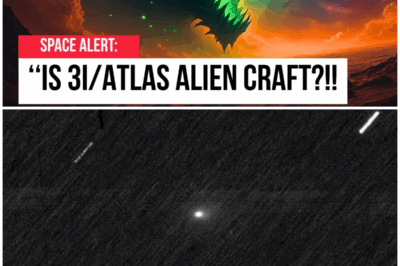

😱 The Terrifying Transformation of 3I/Atlas: Is It More Than Just a Comet? 😱

On September 14th, an interstellar comet named 3I/Atlas shattered every prediction, erupting in brightness and revealing a ghostly green shroud half a million kilometers wide, eight times richer in carbon dioxide than in water.

Its sudden surge left even veteran astronomers reeling as message boards and official channels lit up with confusion and alarm.

At this moment, 3I/Atlas is accelerating toward a close pass by Mars, trailing an anti-tail pointed at the sun, while most major observatories have fallen silent.

The closer 3I/Atlas drifts to Mars, the more terrifying it is becoming.

What has triggered such a cosmic outlier?

And why is critical data vanishing just as the mystery deepens?

The answers challenge our definitions of nature, technology, and secrecy.

Numbers began to break ranks on the night of September 7th.

Spreadsheet jockeys, some in Tokyo, others in Arizona, watched their live plots twist off script.

3I/Atlas, supposed to brighten by fractions of a magnitude per week, instead leapt by plus 1.6 in less than 72 hours.

The first raw measurements timestamped and uploaded by amateurs like Robert McNort and K. Yoshimoto landed at an open magnitude of 10.4 at 2300 UTC, then jumped to 8.8 just before dawn.

A surge like that isn’t just a footnote; it’s a siren.

Within hours, the comet OBS mailing list and Cloudy Nights forum filled with fresh data points.

Each plotted dot vaulted above the forecast curve.

The usual slow climb had become a vertical wall.

A jump of 1.6 magnitudes means the comet was suddenly reflecting four times more light than models allowed.

Think of a dimmer switch cranked to full in the middle of the night.

Some argued it was an outburst, a pocket of CO2 venting through the crust.

Others whispered about instrument artifacts, aperture effects, and the risk of mistaking too much coma for a true flare.

But the numbers kept coming, each new entry a challenge to the old rules.

The story for a few electric hours belonged to the night owl amateurs.

Their raw plots posted in real-time became the pulse of a global skywatch.

No one knew what the next data point would bring, but everyone understood the stakes.

When the light curve breaks, the cosmos is telling you something you don’t yet have words for.

The numbers are staggering.

As of mid-September, 3I/Atlas, a nucleus no wider than 3 km—possibly much less—was venting carbon dioxide at a rate of 129 kg per second.

For scale, that’s a small truckload of frozen gas vaporizing every minute from a body smaller than most city parks.

Hubble’s sharpest images cap the solid core at roughly 2.8 km across.

Yet, the coma—the hazy envelope of gas and dust—has ballooned to more than 700,000 km in diameter.

That’s nearly twice the distance from Earth to the moon, all traced back to a single frigid speck.

This isn’t just a matter of size; the chemistry itself refuses to behave.

Most comets in our solar system wake up gradually, driven by water ice sublimating as sunlight creeps in.

Here, water is a bit player.

The James Webb Space Telescope, with its August 6th spectrum, revealed a carbon dioxide to water mixing ratio of 8:1.

That’s not just unusual; it’s off the scale.

At these distances, solar system comets typically show more water than carbon dioxide, often by a factor of 10 or more.

The numbers for 3I/Atlas defy that hierarchy.

Carbon dioxide dominates, with water trailing far behind and carbon monoxide running a distant third.

The JWST team, led by spectroscopist Dr. Alesia Fronzi, flagged the anomaly in early data releases.

Her group’s models predicted a slow ramp-up of activity as the comet approached the sun.

But the reality was a runaway greenhouse, with carbon dioxide pouring out well beyond where water should even begin to stir.

In her own words, “We’re seeing a comet whose engine is running on a different fuel entirely.”

The implications don’t stop at chemistry.

High-resolution images from ground-based arrays and orbiting telescopes show the coma laced with dusty plasma filaments—thread-like structures stretching tens of thousands of kilometers, twisting and shifting on time scales of hours.

These aren’t the broad uniform clouds familiar from garden-variety comets.

Instead, they hint at non-equilibrium processes, maybe even organized outflows, as if the nucleus is riddled with jets or vents channeling gas and dust into space in discrete, forceful streams.

All of this from a nucleus so small its surface area is barely enough to account for the observed gas output.

Physics demands a minimum of 8% active surface to match the measured water production alone, and the carbon dioxide rates suggest even more aggressive venting.

Grain lifting models posit that carbon dioxide eruptions are lofting fine submicron ice grains into the coma, where they sublimate far from the core, feeding the envelope’s vast reach.

It’s a mechanism rarely seen at this scale.

The scale mismatch is hard to overstate—a city-sized rock wrapped in an atmosphere that dwarfs planets.

Gas output that outpaces models by orders of magnitude.

Chemistry that reads like a recipe from another solar system.

For now, the numbers stand as their own warning.

Something about 3I/Atlas is rewriting the rules of cometary physics, one kilogram of carbon dioxide at a time.

Color theory is not supposed to haunt astronomers.

But by September 16th, the numbers on 3I/Atlas’s spectrum forced a new kind of reckoning.

A spike at 518 nanometers, smack in the heart of the green, cut through the noise sharper and earlier than anyone had penciled into their models.

Photometric logs from Gemini South flagged the uptick first.

The imaging pipeline managed that week by Catalina Hernandez stamped every frame with an asterisk.

Her private note to colleagues read, “The green envelope cut through the pre-dawn sky like a chemical torch—unexpected for this heliocentric distance.”

The green wasn’t subtle.

Visual observers across three continents reported the same eerie glow, often describing it as unnatural, almost electric.

For those fluent in comet chemistry, this hue means C2—diatomic carbon—set aglow by solar ultraviolet.

Normally, comets save their green for the inner solar system, the pigment blooming only as sunlight strips apart organic molecules.

Here, the effect arrived weeks ahead of schedule and at a strength that defied the rule book.

Hernandez’s team measured the emission line’s intensity and found it rivaled the brightest comets ever recorded, even though Atlas was still far from the sun’s furnace.

The technical explanation is simple on paper.

C2 fluorescence is a byproduct of carbon-rich material liberated and energized as the comet heats up.

What’s not simple is the timing.

Models built on decades of comet surveys predict a gradual ramp.

You see two lines rising as the nucleus crosses certain temperature thresholds.

Atlas ignored the script.

Spectrographs from Chile, Poland, and Hawaii all showed the same early crescendo.

The green line punched through background noise with a confidence that left little room for doubt.

Hernandez insisted on caution, circulating raw and processed images side by side, highlighting the risk of digital artifacts.

“We’re not chasing ghosts,” she wrote.

But this is a regime where ghosts can look real.

Still, the consensus grew.

The green was intrinsic, not a trick of the lens.

The comet’s coma, already swollen to planetary scale, now wore a spectral badge that set it apart from every other interstellar visitor.

Some speculated about an ultra-dense ejection of carbon chains, others about exotic chemistry seeded by the object’s distant birthplace.

Each hypothesis added a layer to the mystery, but none could explain why the green arrived so soon or why it burned so brightly.

The effect was hypnotic.

For a few nights in mid-September, the sky offered a spectacle that seemed to defy both distance and expectation.

The numbers told a story of energy and chaos, of molecules torn apart and recombined in the cold vacuum between stars.

But behind every analysis, a question lingered.

What kind of object wears an emerald halo before it should?

And what else is it hiding in its light?

A spike of light, sharp and sunward, split the comet’s envelope just after September 9th.

Not the usual tail, this was an anti-tail—a needle of dust apparently pointing back toward the sun itself, defying the textbook rule that comet tails always stream away from solar wind.

The geometry behind this illusion is rare.

3I/Atlas sweeps in on a retrograde orbit nearly 175° off the ecliptic, and Earth’s line of sight happens to slice almost edge-on through the dust plane.

For a few nights, the comet’s dust disc and the observer’s vantage aligned so perfectly that particles shed months ago, now lagging far behind, seem to project forward, sunward, by the trick of perspective.

It’s a fleeting alignment, but one that turns the comet’s dust into a luminous spike, visible in deep exposures from Poland to Chile.

But the anti-tail is only the beginning of the puzzle.

Warsaw University’s polarimetry team, led by Dr. Marik Novak, ran a sweep at a phase angle of just 7°.

Their result—a negative polarization minimum of minus 2.7%.

In the world of comet science, that’s a siren.

Most comets flirt with minus 1 or minus 2% at these angles.

A signature of porous, irregular dust grains scattering sunlight back toward its source.

Here, the value is deeper, stronger than any recent comet, including the infamous Siding Spring.

The numbers suggest not just dust, but a dust structure.

Particles organized, perhaps aligned, into filaments or sheets dense enough to polarize light far beyond the norm.

What could sculpt such order?

The chemistry offers a clue.

Atlas’s coma is thick with carbon dioxide, a volatile that can drive both violent jets and fine submicron grains into space.

If the outgassing is channeled by fractures, vents, or even electrostatic forces in the coma, dust could be swept into coherent streams, each one acting like a tiny polarizing filter.

The Warsaw Group’s data, cross-checked with amateur images from the same week, shows the anti-tail’s brightness and polarization peak together, hinting at a common origin.

Phase angle matters.

At 7°, sunlight grazes the dust almost head-on, maximizing the backscattering effect.

Negative polarization at this angle is a hallmark of high porosity aggregates, the kind built in the cold and dark of interstellar space.

But the extremity of the measurement—minus 2.7%—pushes the result into uncharted territory.

No known solar system comet has shown such a deep minimum paired with such an organized dust spike.

For the moment, the anti-tail stands as a silent cipher, visible proof that the dust around 3I/Atlas is not a random cloud but something more ordered, more deliberate.

Whether this order is the product of natural comet physics or a sign of something engineered remains an open question, each new measurement pointing to a structure that is both beautiful and unsettling.

A cosmic geometry that defies easy explanation.

October 3rd, 2025, is circled in red on every mission planner’s calendar.

On that day, 3I/Atlas sweeps past Mars at a distance of 0.19 astronomical units—about 28 million km.

In a season already crowded with comet and asteroid encounters, this is the only interstellar visitor within striking range of a planet.

The opportunity is both rare and fleeting.

Mars orbiters—HiRISE on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, TGO on ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, HRSC on Mars Express—face a chessboard of decisions.

Internal emails later quoted in ESA press summaries describe a divided house—science teams lobbying for every possible frame.

Operations teams weigh the risks of retargeting spacecraft on short notice.

The object’s ephemeris is updated almost daily, leaving little room for error.

Each orbiter has its own constraints—solar panel angles, data bandwidth, instrument safety margins.

The window for imaging is measured in hours, not days.

The context is a sky in overdrive.

In late September, 414P races through perihelion.

R2 SWAN draws headlines with its own close approach to Earth.

A6 Lemon is inbound for a November brush with the sun while a wave of minor asteroids threads the inner solar system.

The effect is a kind of observational triage.

Mission directors must choose—expend precious resources on a comet whose behavior is rewriting the playbook or stick to scheduled campaigns and risk missing a once-in-a-generation event.

Behind the scenes, the pressure mounts.

The swarm of objects crowding the autumn sky only heightens the urgency.

Each candidate for observation is weighed against the singularity of 3I/Atlas—its interstellar origin, its CO2 dominated coma, its history of defying predictions.

Schedules are rewritten.

Imaging protocols, usually locked months in advance, are torn up and rebuilt overnight.

The operational stress is palpable.

Every adjustment carries the risk of missed data or worse, instrument safety violations.

Yet the science case is irresistible.

No Mars orbiter has ever caught an interstellar comet this close to a planet.

The data, if secured, could answer questions about dust structure, outgassing, and the fundamental physics of visitor objects from beyond the solar system.

As October 3rd approaches, the sense of a single unrepeatable chance takes hold.

The sky is busy, but for a few hours, all eyes—automated and human—are locked on one object.

The outcome will not just fill a gap in a crowded season of discoveries.

It will set the tone for how planetary science responds when the cosmos throws open a new chaotic chapter.

Every anomaly needs a yardstick for comet 3I/Atlas.

That baseline comes from its two interstellar forerunners—1I/‘Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019.

Both rewrote chapters in planetary science, but they did so in strikingly different ways.

‘Oumuamua arrived as a riddle—no coma, no tail, a light curve that flickered with rotation, but never outgassing.

Its track through the solar system bent ever so slightly off the path gravity alone would dictate—subtle, persistent, and still unexplained.

Borisov, by contrast, was the textbook interstellar comet.

Its gas and dust followed the rules, with water and carbon monoxide driving activity, and its brightness curve matched models built for solar system visitors.

The numbers made sense; the physics held.

Scientists wary of overreacting to outliers built their expectations for 3I/Atlas on these precedents.

They loaded the data pipelines with routines honed on Borisov’s steady climb and ‘Oumuamua’s stubborn silence.

The expectation was a light curve that would rise with heliocentric distance, a coma that would expand in step with solar heating, an outgassing that would sketch a familiar, predictable arc.

Acceleration data sets from both ground-based and space telescopes were primed to flag any deviation from gravitational motion, just as they had for ‘Oumuamua’s curious drift and Borisov’s classic tale.

The first weeks of observation held close to forecast.

Early photometry showed a gentle rise, the kind that fits neatly inside the envelope of comet models.

Acceleration checks run by teams at JPL, ESA, and Harvard found no sign of non-gravitational push.

The comet tracked its hyperbolic course with precision, its orbit solutions requiring no extra corrections.

For a moment, 3I/Atlas looked like a Borisov repeat—foreign, yes, but one that played by the rules.

Then came September—the magnitude leap, the runaway coma, the CO2 dominated spectrum.

Each new data point stretched the baseline.

Scientists at the Minor Planet Center and the NEO Coordination Center combed through the acceleration logs, searching for any hint of the ‘Oumuamua effect.

None surfaced.

The trajectory, at least so far, remains gravitationally sound.

The anomaly, it seems, is not in the path but in the physics, chemistry, structure, and light—not motion.

The baseline, once a comfort, now frames the mystery.

The evidence points not to a comet on the run, but to one whose internal workings are unlike anything the field has measured before.

In the absence of a non-gravitational smoking gun, the focus sharpens on the object’s chemistry and dust, where the real deviations—and perhaps the real answers—lie.

Speculation thrives where data runs thin.

The idea that 3I/Atlas might be more than a comet—a disguised scout, a technological artifact, or the first deliberate visitor from another star—gains traction.

The arguments hinge on three pillars.

First, the comet’s coma, dominated by carbon dioxide, not water, suggests an engine running on unfamiliar fuel.

Carbon dioxide, they argue, isn’t just a volatile.

In the right configuration, it’s a propellant.

The physics isn’t science fiction.

Direct solar heating can drive carbon dioxide jets, and in principle, a structure built to harvest and expel this gas could maneuver or at least modulate its brightness.

Second, polarization.

The Warsaw team’s measurement of -2.7% at a 7° phase angle is the deepest minimum recorded for any comet in recent memory.

Some podcasters call this a signature proof of organized dust or artificial filaments.

Academics push back, pointing to laboratory analogs—high porosity fractal grains can produce similar effects, especially if charged and aligned by electrostatic forces in a carbon dioxide-rich coma.

The science is messy, but the speculation is tidy—order where chaos should reign, a geometry that whispers of intent.

Third, the data blackout.

September’s missing images and the silence from major observatories have become fuel for a thousand theories.

Is the gap a mundane artifact of solar elongation and scheduling, or evidence of managed information?

The influencers frame it as a pattern—a curtain drawn just as the object grows most interesting.

Scientists, meanwhile, cite the same constraints that have shadowed every comet near conjunction—safety margins, pipeline lags, and the relentless geometry of the inner solar system.

The Fermi paradox looms in the background.

If the universe teems with life, why not camouflage among swarms of natural debris?

Why not slip a probe into the statistical noise of comets and asteroids?

The engineered scenario is seductive—carbon dioxide as camouflage and propellant, polarization as a coded signal, the blackout as a deliberate pause.

Yet each claim rests on the edge of plausibility, forever a step ahead of the evidence.

For now, the data support only what’s seen—a comet that breaks the rules but not the laws of physics.

The rest is a mirror reflecting our own hunger for meaning in the silence between signals.

Hubble’s July frames remain accessible, and the August 6th JWST spectra made their way through the pipeline without delay.

But as the comet’s brightness and behavior shifted into overdrive, the cadence of public releases faltered.

No fresh HST or JWST imagery appears in the official logs for September.

Gemini’s own schedule, usually a public roadmap, shows no reserved slots for 3I/Atlas during the critical window when the light curve broke from the script.

The comet’s angular distance from the sun, once a comfortable 45° in late August, plunges toward 30 by month’s end.

For HST and JWST, these numbers are hard boundaries.

The risk to optics and electronics is non-negotiable.

Even ground-based telescopes, with their own horizon and twilight constraints, face shrinking windows as the comet drifts sunward in the pre-dawn sky.

Amateur networks continue to post logs and photometry, but the high-resolution multiband data from flagship observatories is missing from the public record.

Press offices, so active during the July and August campaigns, offer no new advisories.

The risk is not one of conspiracy but of a blind spot—an object rewriting the rules of comet physics, just as the world’s best eyes are forced to look away.

For those tracking the story, the September drought is a reminder.

Sometimes the universe’s most interesting chapters unfold behind a curtain of routine, policy, and geometry.

Every major sky event draws its own circle of risk.

But 3I/Atlas has forced scenario modelers into late nights and uneasy calculations.

The data drought in September isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s a window where the comet’s most volatile behaviors could unfold unseen.

For those who spend their careers quantifying the improbable, this is the season of thought experiments.

What happens if the nucleus fragments while hidden by the sun?

Could a sudden outburst invisible to Earth nudge the orbit just enough to alter the Mars flyby or send a swarm of fragments on new paths through the solar system?

The math is both sobering and seductive.

A delta V of 10 km/s delivered in a single violent venting could have shifted the encounter from a distant pass to a direct hit on Mars.

That’s not a forecast; it’s a sensitivity—a measure of how little it takes for cosmic dice to land on a different number.

Micro-fragmentation, the slow peeling away of icy shards, would show up as faint periodic brightening.

If only the world’s best telescopes weren’t staring into glare.

No such signal has been confirmed, but absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

The comet’s return to visibility in late November, weeks before its closest approach to Earth at 1.88 astronomical units on December 19th, will offer the first chance to check for debris trails, fresh outbursts, or subtle course changes.

The public wants answers, but the science is awaiting a game in back channels and internal memos.

The language is measured—window of risk, watch for fragmentation signatures, monitor for micro-deploys.

The stakes are epistemic, not existential.

What’s lost in the blind spot is not safety but the opportunity to witness a rare interstellar object rewriting the playbook.

The three pillars still stand: a light curve that broke all forecasts, a runaway carbon dioxide atmosphere, and a level of dust polarization that refuses to fit the mold.

Until the curtain lifts, scenario modelers can only run their simulations, knowing that the next act depends on what the universe decides to reveal.

On September 14th, 2025, the Minor Planet Center recorded a plus 1.6 magnitude surge in 3I/Atlas’s brightness, triggering a global response.

Spectroscopy soon revealed a carbon dioxide-dominated coma over 700,000 km wide surrounding a nucleus less than 2.8 km across.

Unusual polarization readings peaking at -2.7% near a 7° phase angle remain unexplained by current comet models.

Despite public images from the HST, JWST, and Gemini through late August, September data releases became sparse, with no official explanation beyond proprietary data windows and observing geometry.

No non-gravitational acceleration or radio signals have been confirmed.

As 3I/Atlas passed Mars at 0.19 astronomical units on October 3rd, most of its perihelion was hidden behind the sun.

Whether its anomalies reflect rare natural physics or unknown origins, the evidence so far points to a real gap in our understanding.

As new data emerge after conjunction, the answers, if any, will come from what is seen, not what is imagined.

News

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 – HTT

😱 Is Ian Gillan Next? Shocking Retirement Rumors Emerge After David Coverdale’s Exit! 😱 In the world of rock music,…

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 – HTT

😱 The Shocking Truth Behind Ian Gillan’s Retirement Plans: Is It Time to Say Goodbye? 😱 Ian Gillan, the legendary…

😱 Is 3I/ATLAS a Cosmic Seed or a Galactic Trojan Horse? Prepare to Be Amazed! 😱 – HTT

New Evidence Sheds Light on the Enigmatic 3I/ATLAS: A Cosmic Visitor Defying Expectations Since the dawn of telescopic astronomy, interstellar…

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Waltz to Heartfelt Confession: Andre Rieu’s Emotional Birthday Surprise! 😱 What’s the one love song that always melts…

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 – HTT

😱 From Wedding Fiddler to Billboard King: How Andre Rieu Redefined Classical Music! 😱 Andre Rieu did the unthinkable. He…

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 – HTT

😱 Heartbreak in Rock: The Real Reason Behind Ace Frehley’s Untimely Death! 😱 Ace Frehley, the legendary guitarist and founding…

End of content

No more pages to load