# Chapter One: The Bench on Michigan Avenue

The rain over Chicago tonight is the kind that forgets how to stop.

It needles sideways off Lake Michigan, turns the gold of the streetlamps into wet paint, and makes the Trump Tower look like a knife someone tried to wash.

At 7:38 p.m. on the first Thursday in November, Marcus Ashford sits in the back of his Bentley Bentayga, partition up, tablet glowing.

Two hundred pink slips are queued in his outbox. He thumbs SEND.

The layoffs will hit inboxes at 8:00 sharp.

Just numbers.

His driver, Ray—an ex-Marine with a silver buzz cut and zero small talk—slows at the light on Michigan and Wacker.

“Boss,” Ray says, voice low through the intercom, “bench on the right. Woman. Baby. No umbrella.”

Marcus doesn’t look. “Drive.”

Ray doesn’t drive.

In fourteen years the man has never ignored an order. Tonight he does.

Marcus exhales through his teeth and lowers the window. Cold rain slaps his cheek like a warning.

She sits on the far end of the wrought-iron bench, knees drawn up, a red wool blanket pulled over both her and the child. The blanket is too thin; water streams from its fringe. Every few seconds she lifts the corner to check the baby’s face, then tucks it back, whispering something the wind eats.

The baby is quiet. Too quiet.

Marcus steps out. His John Lobb oxfords fill with water on the first stride.

He stops three meters away.

“Ma’am,” he says, the word awkward in his mouth. “You’ll both be sick.”

She looks up. Eyes the color of storm-lit river ice.

“We’re fine,” she lies. Her voice is hoarse, as if she has been shouting into the gale for hours and only now remembers how to speak softly.

The baby stirs, makes a sound like a kitten drowning.

Marcus’s chest does something complicated. He has signed eviction notices for mothers before. He has never heard the sound a three-month-old makes when it forgets how warm felt.

He shrugs out of his charcoal cashmere topcoat (Brioni, custom, warm enough for Davos in January) and drapes it over her shoulders without asking. The coat swallows them both.

“My car is ten steps,” he says. “Heat. Towels. Formula if you need it.”

She studies him the way stray cats study offered tuna: wanting, wary, calculating the teeth behind the hand.

“I don’t take rides from strangers.”

“I’m not offering a ride,” Marcus answers. “I’m offering shelter. Difference.”

A gust rocks the bench. The baby whimpers again.

She stands. Her legs shake; the red blanket slips. Marcus catches it, steadies her elbow. Her skin is colder than the rain.

Inside the Bentley the heater roars like a jet spooling up. Ray has already produced two heated seat blankets and a thermos of miso soup he keeps for his own ulcers. He hands the thermos to the woman and pulls into traffic without waiting for coordinates.

She drinks in small, careful sips. Steam fogs the window.

“What’s your name?” Marcus asks.

“Iris,” she says. “And this is Emma.”

Of course it is.

Silence pools between them, thick as Lake Michigan fog.

Marcus watches her cradle the baby against the coat collar. The child’s cheek is flushed, too hot. Fever, probably. He feels the numbers in his head rearrange themselves: hospital bill, pediatric ER, three nights minimum. He can pay it before his CFO finishes her latte.

Iris speaks first. “I had an apartment in Logan Square. Landlord changed the locks at noon. Said if I couldn’t pay three months, I couldn’t keep the key.” She laughs, a sound like ice cracking on the Chicago River. “I left the stroller inside.”

Marcus’s phone buzzes. Board chair: Layoffs executed?

He turns the screen facedown.

The Bentley climbs the private ramp to 400 North Lake Shore Drive. Marble lobby, retinal scan, a doorman who has never seen his boss arrive with wet shoes and a stranger in his coat.

In the elevator Iris leans against the mirrored wall. Emma has fallen asleep, mouth open, one fist curled against her mother’s neck.

“You live here?” she asks, eyeing the brushed-steel panel.

“Top four floors.”

She whistles softly. “Must be nice.”

The doors open directly into the penthouse. Warm light, white oak floors, the faint smell of cedar from the fireplace no one has lit in three years.

Iris stops just inside, dripping. “I’ll ruin your wood.”

“Wood can be refinished,” Marcus says. “Babies can’t.”

He disappears, returns with a stack of clothes that obviously belong to no woman he knows: soft grey joggers, a Northwestern hoodie two sizes too big, thick socks. His college roommate left them after the ’22 Sugar Bowl.

Iris takes the bundle with trembling fingers. “Guest room?”

“Second door on the left. Shower’s hot. Towels are warm. Take your time.”

She hesitates, then nods. The door closes softly behind her.

Marcus stands in his own kitchen feeling like a trespasser. The island is black granite, cold under his palms. He opens the Sub-Zero, stares at sixteen bottles of sparkling water and a single lemon, closes it again.

Ray appears, holding a soggy red blanket.

“Dryer?”

“Third floor. And Ray—order anything a three-month-old might eat. Organic, hypoallergenic, whatever the internet says.”

“On it, boss.”

Forty-three minutes later Iris emerges. Hair damp, hoodie sleeves rolled four times, Emma asleep against her shoulder in a fresh onesie Ray found on Amazon Prime Now.

The fireplace is roaring—Ray again.

Iris stops in the doorway. “You lit a fire.”

“I remembered how,” Marcus says, and surprises himself with the half-smile.

They sit on opposite ends of the twelve-foot sofa. Between them: a tray of miso soup, grilled cheese cut into tiny squares, and a bottle warmer that looks like a spaceship.

Iris eats slowly, eyes on her daughter.

Marcus watches the flames and waits. He is good at waiting; it’s how he buys companies.

Half a bowl in, Iris speaks. “My husband died in a motorcycle accident on the Kennedy. Eight months pregnant. No life insurance. Hospital billed us for the ambulance ride.” She laughs again, softer. “I was a senior UX designer at Leo Burnett. Took maternity leave. Came back to a re-org. They kept the guy who golfs with the CD.”

Marcus nods once. He knows the CD. He golfs with him too.

“I sold everything that fit in a Civic. Then I sold the Civic. Shelter on Halsted has a lottery for beds. Tonight we lost.”

Emma stirs, makes a small sound. Iris shifts her automatically, the motion practiced a thousand times.

“I kept thinking if I could just keep her warm until morning, I’d figure the rest out.”

Marcus stands. The fire pops.

“I own this building,” he says. “Floor twenty-eight is empty. Two-bedroom corner unit. Yours tonight. Tomorrow we get the stroller out of hock.”

Iris’s eyes narrow. “I don’t do payment plans that aren’t on paper.”

“Good. Neither do I.”

He pulls a legal pad from a drawer, writes in neat block letters:

1. Apt 2804 – 12 mo rent free

2. Senior Designer, Ashford Technologies – $145k + benefits

3. Daycare onsite, opens 6 a.m.

4. Start Monday

5. Rent begins Month 13 @ 30 % market

He signs it, dates it, slides it across the granite.

Iris reads, lips moving slightly.

“You typed this in your head.”

“I dictate to myself when I’m bored.”

She looks up. “Why?”

Marcus thinks of the two hundred emails waiting to be opened, the gala speech he was supposed to give about “corporate citizenship,” the ex-wife who still texts on his birthday.

“Because I just fired two hundred people to shave three-tenths off labor costs,” he says. “Because I looked at you feeding your daughter in a rainstorm and realized I’ve been bankrupt for years.”

Iris studies him for a long moment. The fire settles into steady flames.

“I’ll take the job,” she says finally. “I’ll pay rent starting Month Six. And if you ever treat me like a charity case, I’ll quit on LinkedIn with screenshots.”

Marcus smiles—really smiles, the kind that reaches his eyes and scares him a little.

“Deal.”

Ray appears with a portable crib he assembled while they talked. He sets it by the fireplace like a man laying down a gauntlet.

“Boss, Uber Eats says the organic pears are two minutes out.”

“Tell them to take the service elevator,” Marcus says. “And Ray—take tomorrow off. Paid.”

Ray’s eyebrows climb toward his buzz cut. “Yes, sir.”

Iris stands, swaying slightly. Marcus offers an arm without thinking. She takes it.

“Guest room’s this way,” he says.

She pauses. “You have a guest room?”

“Four. I host no one.”

“Tonight you host two.”

They walk the long hallway. City lights smear gold across the windows. Emma’s breathing is soft and even.

At the threshold Iris stops. “Marcus?”

He turns.

“Thank you for stopping the car.”

He almost says You’re welcome, but the words feel too small. Instead he nods once, the way he closes billion-dollar deals.

Later, after Iris and Emma are asleep behind a closed door, Marcus stands on the terrace in a fresh shirt, rain still falling. His phone buzzes—another board member: Markets open in Tokyo, need your eyes on Q4 guidance.

He powers the phone off, slips it into the pocket of yesterday’s ruined suit, and leaves it on the mat for Ray to dry-clean.

Inside, the fire is down to embers. The portable crib glows faintly in the dark.

Marcus pulls a cashmere throw from the sofa, curls up in the leather chair opposite the crib, and listens to a three-month-old breathe.

Somewhere below, Michigan Avenue keeps drowning.

Up here, thirty-three floors above the city that never sleeps, Marcus Ashford discovers that some spreadsheets can wait until morning.

And for the first time in fifteen years, he falls asleep still wearing his shoes.

News

🔥😱📸 MIND-BLOWING RESURRECTION SHOCKER: Young Julieta Ávila Vanished Into Oblivion on the Deadly Road to San Cristóbal Like a Phantom Swallowed by Fog – 9 Years Later, She Mysteriously Reappears in a Casual Tourist Photo That Defies Death and Ignites Global Chaos! 📸😱🔥

On November 7, 2003, Julieta Ávila boarded a bus in Tuxtla Gutiérrez bound for San Cristóbal de las Casas. It…

🔥😱🏠 HEART-STOPPING HORROR ERUPTS: Innocent Little Boy Vanished Without a Trace in 1987 Like a Lamb Led to Slaughter – 25 Years Later, His Devastated Sister Unearths the Blood-Curdling Truth Buried Deep in the Family Basement! 🏠😱🔥

On October 15, 1987, an 8-year-old boy vanished without a trace on the streets of Guadalajara, Jalisco. For 25 years,…

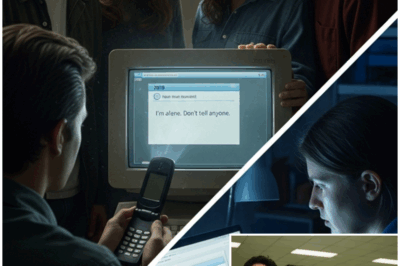

🔥😱📱 UNBELIEVABLE CHILLING MYSTERY EXPLODES: Four Best Friends Vanished Into Thin Air in 2004 Like Ghosts Swallowed by the Night – 14 Years Later, One Sends a Haunting Message from a Brand New Account That Shatters Reality! 📱😱🔥

On March 15, 2004, four college students left Guadalajara for Puerto Vallarta to celebrate spring break. None of them ever…

🚨👧💸 **“HERE’S $50… I JUST NEED A DAD FOR ONE DAY!” — PINT-SIZED ORPHAN IN RIPPED SNEAKERS SLAPPED A CRUMPLED BILL INTO THE PALM OF A HEARTLESS $9 BILLION CEO AND WATCHED HIS EMPIRE CRUMBLE INTO A FAIRY-TALE!** 👑💔🍼

# Chapter One: The Tuesday That Cost Fifty Dollars Tuesday, 3:42 p.m. Central Park, just west of the Delacorte Theater….

🚨👨👧❄️ **“DADDY, HER BABY IS FREEZING!” — 6-YEAR-OLD HEIRESS IN PINK GUCCI SCREAMED, DRAGGING HER RUTHLESS CEO FATHER INTO A RAIN-SOAKED ALLEY WHERE ONE TINY CRY JUST HIJACKED A $40 BILLION EMPIRE!** 👶💔🍼

Chapter One: The Bench on the Upper East Side Snow in Manhattan never asks permission. It arrives in fat, deliberate…

🚨🐕🦺 **BILLIONAIRE’S DOOMED TWINS CRAWLED IN DIAMONDS BUT COULD NEVER WALK — UNTIL THE $8-an-HOUR MAID SMUGGLED IN A FURRY MIRACLE THAT SHATTERED EVERY DOCTOR’S PROPHECY!** 🐶💎😱

The first thing Clara noticed about the Cole mansion was the smell: not roses, not money, but the faint metallic…

End of content

No more pages to load