Here is the opening of your story.

Pressure Level Twelve smelled like hot metal, ozone, and whatever the Air Filtration department currently called “High-Plain Morning Mist.” To Elian, it just smelled like rancid machine oil.

He dragged his fork through the beige, restructured protein cube on his tray. It quivered weakly.

“It’s not going to jump into your mouth, Elian,” Ren said, his voice muffled by a large bite of his own.

Elian looked up. Ren sat opposite him in the Dome Canteen, a vast, sterile expanse of white ceramic and plastic where the only spectacular view—the blue-green marble of Earth hanging above Concordia’s dust-streaked rim—was systematically ignored. Ren was tapping grease-smeared fingers against his tablet.

“It failed again,” Ren announced. He didn’t need to specify what had failed. Ren’s gyroscope project had been failing with rhythmic precision for three weeks. “The sim said it would stabilize at 8-sigma. It does not stabilize. It shakes like a Mercurian dancer in a fit.”

“Did the simulation account for dust?” Elian asked, finally managing to spear a piece of the protein. It tasted exactly like Level Twelve smelled.

Ren froze, fork halfway to his mouth. “Dust.”

“It’s always dust,” Elian said.

“Son of a bitch,” Ren muttered, not to Elian, but to the universe at large. He began typing furiously on his tablet. “Of course. Electrostatic-fucking-clinging on the bearings. It’s attracting micro-particulates. Micro-drag. I should have…” He trailed off, lost in a world of bearing tolerances and sigma deviations.

Elian let his friend submerge. The silence was comfortable. He turned to look out the Canteen’s great viewport. Earth looked peaceful from here. A perfect, silent sphere, showing no sign of the nine billion people scrambling over its surface. Up here on Luna, there were only one hundred thousand. Spacious. Most days, Elian appreciated the space.

Around them, the Canteen hummed with controlled noise. This was Concordia, the Interplanetary University of Engineering and Xen-Archaeology. Everything was controlled. There was no shouting. No overloud laughter. Just the murmur of conversations, the click of cutlery on ceramic trays, and the ever-present, low-frequency thrum of the life support systems. People moved with the slow, deliberate deliberation of one-sixth gravity. No one rushed. Rushing in 0.16g led to undignified collisions and messy landings.

A few tables over, Dr. Aris was eating lunch alone. As he always did.

Aris was the head of Pre-Emergent Linguistics (Elian’s department, student body: three). He was a thin, strung-out man whose thinning hair always stood on end, as if he’d just stuck a finger in a power socket. Today, he wasn’t eating. He was glaring at a tablet, but not a data-slate like Ren’s. Aris’s screen showed what looked like a complex geological scan—a web of subterranean blue and red lines. Every so often, he would mutter something to himself and jab the screen angrily with a stylus.

Elian watched as Aris raised his water cup to his mouth, missed, and tapped the rim of the cup against his own temple. Synthetic water, clear and precious, burst from the cup and splattered across his shirt collar in a cloud of glittering, low-gravity beads.

Aris didn’t even flinch. He just brushed the floating droplets away and returned to his map.

“He’s on it again,” Elian said quietly.

Ren looked up from his calculations. “Hm? Oh, Aris. Yeah. What is it this time? ‘The Signal’?” Ren put audible quotation marks around the word, his personal synonym for “delusional fantasy.”

“I think so. He cancelled two of my lectures this week.” Elian didn’t truly mind; it gave him more time in the acoustic archives.

“Lucky you. My Professor Thorne just decided that the entire theory of plasma propulsion we’ve been using for twenty years is ‘fundamentally flawed’ and assigned a new midterm project. Due Tuesday.” Ren groaned and took another vicious bite of protein. “At least your languages are dead. They can’t change the rules.”

“You have a point,” Elian murmured. He looked back at Aris, who was now cross-referencing the data on his tablet with a thin, paper-bound book—a genuine rarity. His focus was total.

The Canteen’s doors hissed open. Most people didn’t look up. Transits were normal. But Elian had noticed this girl before.

She didn’t move like the others. Most Luna-born or long-term residents had adapted to the low-g with an efficient “glide-step.” They pushed off and let momentum carry them. This girl walked. Each step was deliberate, heavy, weighted, as if she were trying to nail her boots to the floor. As if she was actively fighting the lack of gravity.

She grabbed a tray, not even looking at the options, just stabbing three identical protein blocks, and marched to an empty table in the far corner. She wore the standard-issue engineering coveralls, but hers were stained with something black—grease or paint. Her dark hair was pulled back in a bun so tight it looked painful.

She sat down, her back to the room, and immediately pulled out a sketchbook and a charcoal pencil. She didn’t eat. She began to draw.

Elian found himself staring.

“That’s Saria,” Ren mumbled, not looking up from his tablet. “Reactor Core Design. Notoriously… prickly. I tried to borrow a differential calibrator from her last week. She told me, and I quote, ‘Find your own, Earther-scum.’”

Elian blinked. “I didn’t even know she knew I was from Earth.”

“She knows,” Ren said. “They call all of us ‘Earther-scum’ or ‘Heavies.’ The born-here,” he tapped his own chest, “we’re ‘Lights’ or ‘Natives.’ She’s a purist.”

“Great.” Elian looked back at Saria. She was drawing with fast, angry, powerful strokes. It wasn’t a reactor schematic. It looked like… a face. But the angles were all wrong. Too sharp.

Elian turned back to his food. Lunch, like most things on Concordia, was an exercise in efficiency rather than enjoyment.

After lunch, they returned their trays to the recycler, where a robotic arm scraped the leftovers into a hopper and dipped the plates in a hissing, sanitizing steam bath. Ren was still muttering about dust.

“It has to be the lab’s air filters. They aren’t rated for micron-level particulates at this concentration. I’m going to see the Prefect.”

“Good luck with that,” Elian said. They stepped out into the corridor.

This was Elian’s world. A series of metal, pressurized tubes. The Dome corridor curved with the inner circumference of the crater, its floors polished slick by decades of footsteps. Instead of windows, the walls were lined with high-resolution screens. Most were set to idealized Earth-scenes: Swiss forests, Pacific beaches, Iguazu Falls. They were supposed to combat ‘spatial deprivation.’

Ren reached out as they passed a view of the Amazon rainforest and slapped the ‘off’ panel. The screen went dead gray.

“Hate these,” Ren said. “Too much green. And damp. Looks unhygienic.”

They passed a maintenance bot—a cylindrical canister on wheels—that was fruitlessly trying to clean a scuff mark on the floor. It kept rolling over the spot, emitting a frustrated beep-boop, but its scrubber arm was misaligned and missed the mark by three centimeters every time.

“That one’s been in a sensor-loop for three days,” Ren noted.

“You going to fix it?”

“Not my department.” Ren patted the bot’s chassis as they passed. “Keep trying, Bleep.”

The bot beeped angrily and bumped into the wall. Ren chuckled.

They reached a junction. Left led to Engineering, a maze of labs, workshops, and what Ren affectionately called “The Pit.” Right led to Humanities, a much quieter wing that smelled of old servers and, faintly, archival paper.

“Right,” Ren said, slapping his tablet. “I’m off to fight the dust. You got class? Dead hieroglyphs or something?”

“The library,” Elian said. “I’ve got a meeting with my advisor at 16:00.” His wrist-com vibrated gently. A reminder. Dr. Aris. 16:00. Office.

“Aris? Thought he cancelled on you?”

“This is about something else.” Elian felt a vague knot of anxiety. Aris never called for meetings unless it was important. “Probably about my translation work.”

“Right. Well. Don’t get lost in your runes.” Ren clapped Elian on the shoulder—a well-intentioned gesture that nearly sent Elian off-balance in the low-g—and glided off toward The Pit, already muttering about friction coefficients.

Elian stood alone in the hallway. The frustrated beep-boop of the maintenance bot echoed behind him. He turned right, toward the quiet of the Humanities wing.

Elian’s “office” was a small research carrel in the library’s acoustic archive. It was his sanctuary. It had no windows, just sound-dampened gray walls and a large, wrap-around workstation. The air in here smelled different—hot, aging servers and the faint, acidic tang of paper decay from the sealed physical-storage vaults.

He sat down and put on his headphones. His monitor flickered to life, not with Akkadian texts or Sumerian cuneiform, but with something else entirely.

It was an audio file. Its waveform was complex, non-recursive. The file label read: TR-7.ANOMALY.REC-009.

This was his real work. Not the dead languages he told everyone about. This.

It had been detected eighty years ago by an unmanned probe in the Kuiper Belt. A signal. A repeating, non-cyclical burst of sound, emitting from a point of empty space, aimed somewhere out past Saturn. Most scientists had written it off as plasma interference or a bizarre, natural stellar phenomenon.

Dr. Aris did not. And now, neither did Elian.

Elian hit ‘play.’

The sound flooded his ears. It was not music. It was not speech. It was a series of clicks, high-pitched whistles, and a deep, textured rumble that was almost below the threshold of hearing. It made his teeth itch. It always did. It had a rhythm, but a rhythm his human brain couldn’t quite parse. It was like listening to an ocean sing complex mathematics.

He closed his eyes. This was the “other world.” Not Luna, not Earth. This was Deep Space. The Cold. The Vast.

He had spent the last year trying to find a structure. His boss, Aris, believed it was a language. Aris believed it was made. Elian… Elian wasn’t sure.

He opened another file, a spectral analysis program he’d coded himself. It translated the audio into visual patterns. As the audio played, lines began to form on the screen. Complex peaks and valleys, fractal spirals of overlapping harmonics. It was strangely, chaotically beautiful.

He worked. He lost track of the Canteen, of Ren, of the Earth hanging in the sky. He tweaked the filters, isolating one specific frequency—a high, reedy whistle that repeated every 37.2 seconds. He was trying to map its relationship to the underlying bass-rumble.

Abruptly, an image flashed in his mind. Unrelated.

Saria’s hand. The sketchbook. The angry charcoal lines.

He frowned, reaching for his personal tablet. He’d taken a quick, surreptitious photo while Ren was talking. It was a bad habit—documenting things. He pulled up the image. It was blurry, taken from across the room. But the shape was clear.

Saria hadn’t been drawing a face.

He looked at the blurry photo. Then he looked at his workstation monitor, where the spectral analysis program was painting the “language” of TR-7.

Elian stood up abruptly. His chair, held by minimal gravity, floated backward and hit the sound-dampened wall with a soft thud.

He zoomed in on the photo of Saria’s drawing. Then he froze the frame of his spectral analyzer.

They weren’t identical. Her drawing was raw, angular, emotional. His analysis was precise, mathematical, cold.

But the structure. The spirals. The relationship of the primary angles.

Elian felt a cold, physical lurch in his stomach, a purely terrestrial reaction he couldn’t control.

She was drawing the Signal.

The smell was the first thing. Ozone, and underneath it, the coppery-metallic tang of the primary conduit junction. It was a smell Kael associated with headaches. He pressed his palm flat against the vibrating bulkhead, feeling the ship’s faint, asthmatic tremor through his bones.

“It’s not the coupling,” Ria said, her voice tight with annoyance. Her own diagnostic slate was balanced on a coolant pipe, its green-on-black text scrolling in endless, useless columns. “I’ve run the check three times. The coupling is nominal.”

“‘Nominal’,” Kael murmured, tasting the word. It was the ship’s favorite word. Everything was nominal, right up until the moment it was catastrophic. He shifted his weight, the magnetic soles of his boots releasing their grip on the gantry with a soft shh-thunk before locking on again. Below his feet, three kilometers of starship dropped away into a darkness sliced only by red service lights. “It’s the buffer. Has to be.”

“The buffer is rated for another four thousand cycles.” Ria wiped a smear of graphite grease from her cheek, succeeding only in spreading it. “Maintenance logs say it was swapped by Alpha Shift. You calling Alphas liars?”

“I’m calling them lazy,” Kael said, without heat. He began unspooling a fresh data probe from his tool belt. The new probe’s yellow casing was bright, almost offensive in the grey dimness of Service Tunnel 8-Delta. “They reset the log, not the part. They do it all the time. Means they get to clock out seventeen minutes early.”

Ria sighed, a long, drawn-out sound that was swallowed by the ambient hum. “Seventeen minutes. What I’d give for seventeen minutes. My application for the Hydroponics rotation got denied. Again.”

Kael paused, probe in hand. “I thought you hated plants.”

“I hate this,” she gestured, taking in the conduit, the gantry, the oppressive, functional grey. “At least in Hydroponics, the air smells like dirt. And Joram from Agri-systems? He owes me for that time I rerouted power to his sector during the Level 5 blackout. I thought he’d put in a good word.”

“Joram’s a pencil-pusher. He probably logged your favor as a system error.” Kael plugged the probe into the socket. His own slate lit up, this one projecting a faint blue schematic into the air in front of him. He manipulated the image, his fingers tracing lines of light. “See? Look at the energy decay. Point-seven-three. It’s bleeding power. They didn’t swap the buffer.”

Ria leaned over, the light from his slate illuminating the sour set of her mouth. “Fine. You win. We get to spend the next three hours wrestling a two-hundred-kilo component while Alpha shift is in the mess hall complaining about the synth-paste. Fantastic.”

Kael didn’t reply. He was already working, his movements economical and precise. He toggled the comms link on his collar. “Bridge, this is Tech Kaelen, Service 8-Delta. Requesting temporary power-down to Junction 114. We have a faulty buffer, cycle-log discrepancy.”

The reply was instantaneous, a synthesized female voice devoid of inflection. “Request denied, Tech Kaelen. Junction 114 is critical for Life Support, Decks 40 through 50. Resubmit request during non-peak cycle.”

“Non-peak cycle,” Kael said to the air. “That’s 0300.”

“Of course it is.” Ria kicked the bulkhead, a dull thud that vibrated in Kael’s teeth. Her boot left no mark. “So, what now, boss? We file the report and let this thing blow during Gamma shift?”

Kael stared at the schematic. The decay was slow, but it was steady. If it arced, it could take out filtration for three entire habitat levels. He toggled his comms again. “Bridge, log the request. I’m initiating a cold-swap bypass. Authorize maintenance override, code 9-Epsilon-Tango.”

There was a pause. Even the synthetic voice seemed to hesitate. “Override 9-Epsilon-Tango requires Level 4 authorization. A cold-swap bypass is… non-standard. Awaiting confirmation.”

“She’s checking with a real person,” Ria whispered, suddenly still. “You’re going to get us flagged.”

“It needs to be done.” Kael pulled a heavy, insulated wrench from his belt. “And it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than for a non-peak cycle.”

“Authorization granted, Tech Kaelen,” the voice returned, almost reluctantly. “System integrity is now your responsibility. Log all procedures. Bridge out.”

A heavy clunk resonated through the tunnel as the primary safety locks disengaged. A new light, this one a stark, angry amber, began to flash above the junction box.

“Your funeral,” Ria said. But she was already moving, grabbing a grounding clamp from her own belt. “You touch the bypass, I’ll ground the spill-over. Try not to fry us. My application for sanitation recycling is still pending.”

“I’ll do my best,” Kael said, and began to work.

Two hours later, slick with sweat that smelled like recycled water and hot metal, they sat on the gantry, sharing a lukewarm ration bar. The amber light was gone. The low, steady hum had returned.

“You’re a lunatic,” Ria said, but she passed him the last piece of the bar. “A cold-swap. My hands are still shaking.”

“It worked.” Kael tucked the silver wrapper into his pocket. Waste discipline was drilled into them from birth. “And the buffer is new. Good for another eight thousand cycles.”

“Eight thousand,” Ria snorted. “We’ll be molecules by then. C’mon. I want to wash this smell off me before the mid-shift rush at the mess.”

They walked back, their mag-boots clicking in unison. The transit system was quiet. They passed two security patrols, their white-and-red armor gleaming under the corridor lights, and a sanitation drone that hummed past, dutifully scouring the floor panels. In one of the communal alcoves, Kael spotted Old Man Elara, his white hair a stark contrast to his dark engineer’s overalls. Elara was bent over a small, complex object in his hands, muttering to himself. As they passed, Kael saw what it was: a tiny, floating needle suspended in a liquid-filled glass disc.

“Still working on that thing?” Ria called out, not unkindly.

Elara looked up, his eyes bright and unfocused, as if pulling himself back from a great distance. “Ah, young Ria. Young Kaelen. It’s the magnetism. The core drive plays havoc with true north. But I’m close. I’m very close.”

“There is no north, Elara,” Ria said, tapping the metal wall. “Just ‘Forward’ and ‘Aft’.”

“But where is forward going?” Elara smiled, a network of deep wrinkles fanning from his eyes. He tapped the glass disk. “This… this remembers. Even if we don’t.”

Ria rolled her eyes, but she gave the old man a small wave as they moved on. “He’s going to get recycled with that compass in his hand, I swear.”

“He likes it,” Kael said. “It gives him something to fix.”

“We’ve all got something to fix,” Ria countered, as the doors to the Deck 45 Mess Hall hissed open.

The room was vast, echoing, and already half-full. The air was thick with the smells of steam, boiled synthetics, and the sharp tang of the cleaning solution they used on the tables. A low-B decibel announcement played on a loop, reminding citizens to report any deviations in light quality.

They got their trays. A grey, vitamin-enriched paste; a cube of textured protein, allegedly “chicken-flavored”; and a cup of water that tasted faintly of the filtration unit. They found a table near the wall, away from a rowdy group of off-duty cargo handlers who were engaged in a loud, arm-wrestling competition.

“I heard,” Ria said, lowering her voice and leaning in, “that they sealed Sector 7-Alpha. Permanently.”

Kael stopped, his spoon halfway to his mouth. “Seven-Alpha? That’s just storage. Old archive servers.”

“That’s what the manifest says.” Ria took a bite of the paste, grimacing. “But Talla, from Logistics? Her cousin works in air filtration. He said they shut down the vents. Not cycled, shut. Down. No air, no heat, no power. Just welded the hatches.”

Kael looked around. No one was paying them any attention. The cargo handlers were laughing. A young woman at the next table was sketching on a data slate, her brow furrowed in concentration as she designed a new pattern for a uniform patch. “Probably a contamination leak. Old servers are full of heavy metals.”

“No,” Ria said, her eyes intense. “No alarms went off. No biohazard warnings. Just… sealed. Talla said her cousin’s been reassigned, and his old access codes were wiped an hour later. He’s terrified.”

Kael considered this. It was strange. But the ship was a place of a million strange, unexplained rules. A sealed sector was unsettling, but it didn’t affect his work. “It’s above our pay grade, Ria. Don’t go looking for trouble.”

“I’m not looking for trouble,” she muttered, poking at her protein cube. “I’m just saying, it’s not nominal.”

Kael glanced up at the wall-mounted monitor. It was displaying the standard exterior view: a static, algorithm-generated starfield. They’d reset it after the ‘Great Void’ incident three generations back, when the reality of the endless, unchanging blackness had supposedly caused a psychological epidemic. Now, the view was a comfortable, glittering simulation.

As he watched, a single pixel on the screen flickered. It went from white to red, then back to white. It was a tiny, almost imperceptible glitch. A bad display, nothing more.

He turned back to his food. The paste was cold. He was tired. His shoulders ached from wrestling the buffer. He thought about the 0300 non-peak cycle, and the four thousand cycles Elara was chasing, and the seventeen minutes Alpha shift had stolen. He took another bite. The glitch, he decided, was just another thing to fix.

News

🔥😱📸 MIND-BLOWING RESURRECTION SHOCKER: Young Julieta Ávila Vanished Into Oblivion on the Deadly Road to San Cristóbal Like a Phantom Swallowed by Fog – 9 Years Later, She Mysteriously Reappears in a Casual Tourist Photo That Defies Death and Ignites Global Chaos! 📸😱🔥

On November 7, 2003, Julieta Ávila boarded a bus in Tuxtla Gutiérrez bound for San Cristóbal de las Casas. It…

🔥😱🏠 HEART-STOPPING HORROR ERUPTS: Innocent Little Boy Vanished Without a Trace in 1987 Like a Lamb Led to Slaughter – 25 Years Later, His Devastated Sister Unearths the Blood-Curdling Truth Buried Deep in the Family Basement! 🏠😱🔥

On October 15, 1987, an 8-year-old boy vanished without a trace on the streets of Guadalajara, Jalisco. For 25 years,…

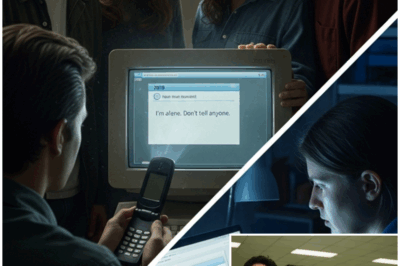

🔥😱📱 UNBELIEVABLE CHILLING MYSTERY EXPLODES: Four Best Friends Vanished Into Thin Air in 2004 Like Ghosts Swallowed by the Night – 14 Years Later, One Sends a Haunting Message from a Brand New Account That Shatters Reality! 📱😱🔥

On March 15, 2004, four college students left Guadalajara for Puerto Vallarta to celebrate spring break. None of them ever…

🚨👧💸 **“HERE’S $50… I JUST NEED A DAD FOR ONE DAY!” — PINT-SIZED ORPHAN IN RIPPED SNEAKERS SLAPPED A CRUMPLED BILL INTO THE PALM OF A HEARTLESS $9 BILLION CEO AND WATCHED HIS EMPIRE CRUMBLE INTO A FAIRY-TALE!** 👑💔🍼

# Chapter One: The Tuesday That Cost Fifty Dollars Tuesday, 3:42 p.m. Central Park, just west of the Delacorte Theater….

🚨👨👧❄️ **“DADDY, HER BABY IS FREEZING!” — 6-YEAR-OLD HEIRESS IN PINK GUCCI SCREAMED, DRAGGING HER RUTHLESS CEO FATHER INTO A RAIN-SOAKED ALLEY WHERE ONE TINY CRY JUST HIJACKED A $40 BILLION EMPIRE!** 👶💔🍼

Chapter One: The Bench on the Upper East Side Snow in Manhattan never asks permission. It arrives in fat, deliberate…

🚨🌧️ **ICE-HEARTED CEO IN $100K TAILORED ARMOR STUMBLED UPON A RAIN-DROWNED MADONNA CRADLING HER LAST DROP OF HOPE — WHAT HE WHISPERED MADE THE ENTIRE CITY FORGET HOW TO BREATHE!** 👶❄️💧

# Chapter One: The Bench on Michigan Avenue The rain over Chicago tonight is the kind that forgets how to…

End of content

No more pages to load